Excavating South Korea’s Nuclear History

Diplomatic records and oral histories offer leads into South Korea's nuclear past, while other sources remain out of reach.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Diplomatic records and oral histories offer leads into South Korea's nuclear past, while other sources remain out of reach.

Diplomatic records and oral histories offer leads, while other sources remain out of reach

Anyone could tell you that secrecy and limited access to North Korean sources constrain our understanding of the Hermit Kingdom’s nuclear intentions and technical capabilities.

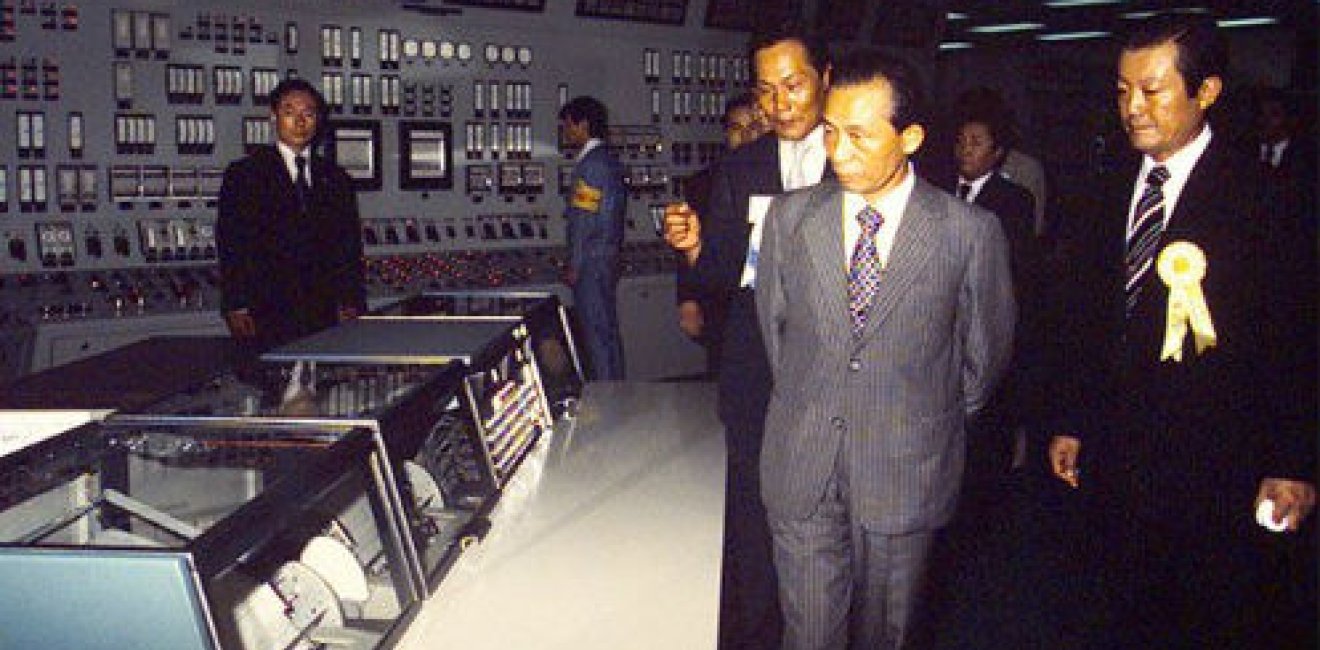

Yet these same problems inhibit historical research on a much more open country, South Korea, which had its own aspirations to develop nuclear weapons in the 1970s. Known as “Project 890,” the clandestine military nuclear program started in 1972 and its existence was discovered by Washington only in late 1974.

More than four decades later, South Korea’s past ambitions have become a case study in nuclear proliferation. But inside sources documenting Project 890 are sparse, leaving historians to rely on oral history interviews and media reports.

Why is this the case? Like many other democratic countries, South Korea has a national archives system that makes declassified documents available to the public, usually after a period of 30 years. Yet few documents directly related to Project 890 can be found in South Korea’s archives.

The extreme secrecy surrounding nuclear weapons programs generally makes it difficult for researchers to grasp the whole picture of most countries’ programs. In the South Korean case, secrecy combined with President Park Chung Hee’s authoritarian rule, makes conditions even more challenging for historical research. Opaque document management practices under President Park suggest that some records were destroyed.

Other documents disappeared when Park was assassinated in 1979. Oh Won-chul, then Blue House Senior Staff for Economic Affairs, claims confidential documents about Project 890 were kept in Park Chung Hee’s personal safe. Allegedly, they were handed over to the new military government of Chun Doo-hwan in 1980. But when Oh visited the National Archives years later he was not able to find them. Oh suspects that Chun might have turned the confidential documents over to the United States, but proof of this has yet to surface.

The Ministry of Science and Technology (MIST), the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI), and the Agency for Defense Development (ADD) also participated in Project 890. Yet many 1970s documents from KAERI and ADD are believed to have been improperly stored and then lost, while access to MIST documents remains complicated because the National Archives of Korea does not provide detailed finding aids.

Nevertheless, tracking South Korea’s nuclear weapons program is not an impossible task. Media interviews with key stakeholders in Project 890 describe the contents of some un-released documents. For instance, Oh described a Blue House paper that he submitted to President Park in 1972 in which he concluded that South Korea should develop plutonium bombs.

While Oh is the most outspoken figure among the Blue House officials involved in Project 890, there are others, such as Kim Jung-ryum and Sun Woo-yeon. Recently, Oh’s statement was confirmed with further details by another former staff member, Kim Kwang-mo, who wrote a draft of the paper. Former Prime Minister Kim Jong-pil also told the media that he asked the French President to export spent fuel reprocessing facilities to South Korea in 1973.

Limited access to written evidence leads historians to rely on interviews with former Korean officials. In addition to these high profile officials, interviews with lower-level researchers and officials in the project can be found in the existing literature. While such interviews help trace South Korea’s nuclear history, historians must consider that memories can be distorted, consciously or not, unless they are corroborated by hard evidence such as archival sources.

South Korea’s relatively well-preserved diplomatic records remain the best bet for current research. The military program proceeded in parallel with Korea’s civilian nuclear energy efforts and some technology was transferred between the two programs.

Much of the civilian project depended on negotiations with foreign nuclear suppliers—the United States, France, and Canada—to acquire technology and facilities that could be converted for military use when necessary. While the technical aspects of civil nuclear cooperation were directed by other ministries and agencies, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was the primary government body representing Korea’s interests in nuclear negotiations with foreign governments. Many examples of correspondence with other ROK ministries, agencies, and the US Embassy in Seoul regarding nuclear issues can be found at the ROK Diplomatic Archives.

These diplomatic records will not fully reveal the military side of South Korea’s nuclear ambitions, but they are a starting point to understand the ROK’s early nuclear endeavors and later nuclear weapons program.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more