In September 1947, after more than a year of stop-start negotiations, the United States and the Soviet Union reached a breaking point over the fate of Korea.

Two years earlier, at the end of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union had each granted themselves control over one half of Korean territory. The division of the peninsula was intended to be temporary, a provisional measure while the Allied powers worked out the particulars surrounding Korea’s independence. The two powers described the arrangement in sophisticated terms – it was a “trusteeship.” The rationales for the joint occupation of Korea, a colony under complete Japanese control during the war, are difficult to appreciate in retrospect.

In December 1945, the United States and the Soviet Union moved forward on their promise to shepherd Korea toward self-government when they reached the so-called “Moscow Agreement.” The two countries formed a Joint Commission, tasked with preparing an independent, unified Korean government on the peninsula and cultivating Korean leaders and political organizations toward this end. The US-Soviet Joint Commission met often in Seoul and Pyongyang in spring 1946, and, after a lull, resumed negotiations in spring and summer 1947.

Unfortunately for the Koreans, progress was hard to come by, and the Joint Commission deadlocked again. At the same time as Joint Commission negotiations stalled, George Marshall and V.M. Molotov –the US Secretary of State and the Soviet Foreign Minister, respectively – began sending each other courteous but resentful letters, one side always blaming the other and laying out contradictory pathways for the Joint Commission to resume (and, hopefully, complete) its mission. The letters are text book examples of passive aggressive diplomacy.

By September 12, the Soviets had waited over a week for Marshall to respond to their latest note. The leadership in Moscow assumed one would come, and continued to strategize next steps. Jacob Malik – then Deputy Foreign Minister – suggested that the Joint Commission could reconvene soon. He believed, apparently, that the US and the Soviet Union were not far from reaching a modus vivendi. Soviet negotiators at the Joint Commission, he said, should advocate for creating a Provisional All-Korean People’s Assembly, a body composed of representatives from both northern and southern Korea that could advise the Joint Commission. Stalin approved Malik’s proposal.

Then came the breaking point. On September 17, responding to Molotov’s latest message, the United States announced that it was jettisoning the Joint Commission. Instead of further bilateral talks, the US would turn the issue of Korean independence over to the United Nations.

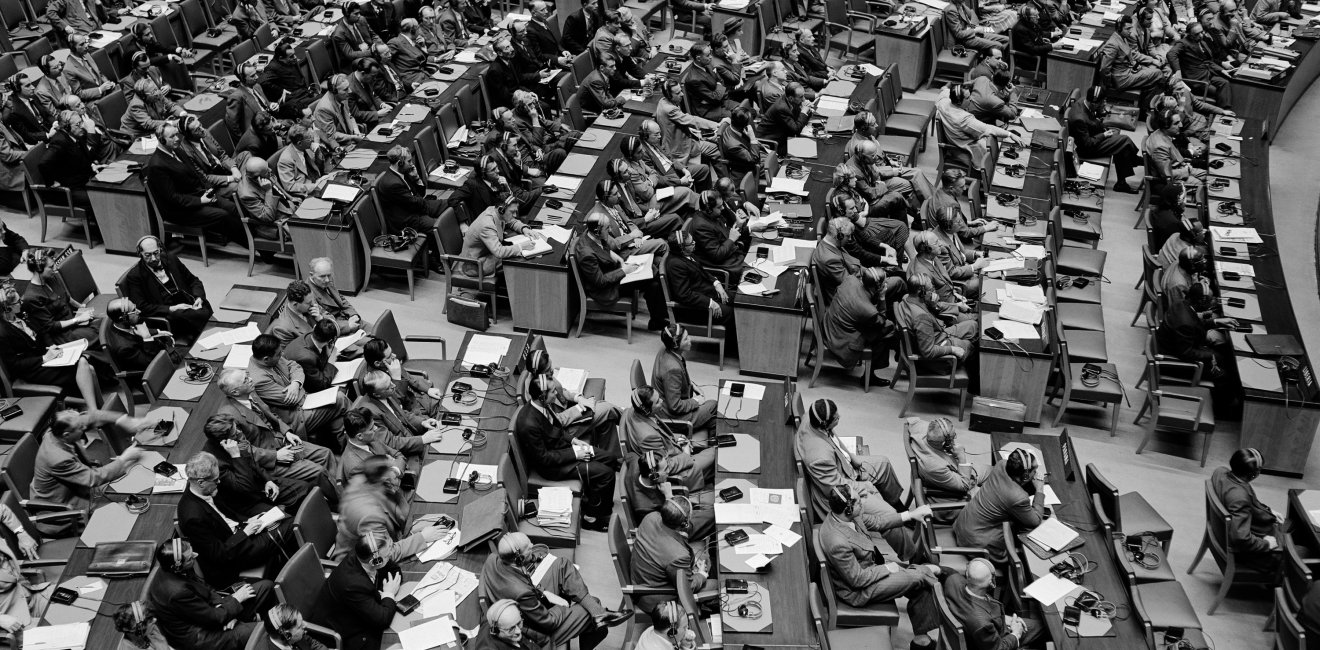

Several hours after sending the note to the Soviets, Secretary of State Marshall announced the United States’ new position in a speech before the United Nations General Assembly. Pointing his finger at the Soviet Union, Marshall concluded “that further attempts to solve the Korean problem by means of bilateral negotiations will only serve to delay the establishment of an independent, united Korea.”

Marshall’s speech sent the Soviet government into a frenzy. Andrey Vyshinsky, the Deputy Foreign Minister then in New York for the UNGA proceedings, demanded an “immediate reply.” Molotov called Marshall’s statements “incorrect and unacceptable,” and said they merited a “comprehensive reply and criticism.” Vyshinsky was instructed to demonstrate, before the UNGA, that Marshall’s speech was a “violation of the commitments which the United States took upon itself” in regards to Korea.

(It should be noted that Marshall covered a lot of ground in his UN speech, from nuclear proliferation to Greece to Palestine and Korea – and pretty much everything he said frustrated the Soviets.)

Vyshinsky did as ordered the very next day, in a speech the New York Times called “stunning.” “[Delegates] expressed shock and dismay at the fury of the attack,” the front-page article read.

Behind the scenes, the Soviet leadership undertook a strategic reassessment. In a private letter to Stalin, Molotov reiterated that their government had previously been willing to compromise with the Americans. But Marshall’s surprise speech had changed negotiation dynamics so fundamentally that an entirely new approach was needed. The Soviet Government should propose, Molotov wrote, the withdrawal of all foreign troops from Korea. In effect, this would put the Koreans in charge of their own fate rather than a multilateral body operating at America’s initiative. “Such a statement will be a good reply to Marshall’s statement and upset his plans in the Assembly.”

The next several weeks saw continued Soviet-American politicking at the UN General Assembly and in other fora to get their respective ways on Korea. On September 26, the Soviets announced their proposal to withdraw all foreign troops from the peninsula by early 1948. On October 10, Molotov lambasted George Marshall in another letter.

On October 17, Marshall responded to Molotov; the same day, the United States introduced its draft resolution on Korea (Document A/C.1/218) calling for the creation of a UN Temporary Commission to organize elections by March 1948.

The Soviets flatly rejected the American initiative, insisting that their proposal to withdraw foreign troops from Korea should be considered in the UN General Assembly before any discussion of UN-organized elections. Furthermore, the Soviet government argued that the entire debate should come to a stop until Korean representatives were invited to the United Nations to participate. Draft resolutions for these Soviet initiatives were submitted on October 29 (Document A/C.1/229 and A/C.1/232) – but both were voted down.

The US-sponsored resolution passed the General Assembly on November 14. The Soviet Union and its closest allies refused to cast votes, with Vyshinsky arguing that it was “incompatible with the principles of self-determination.”

Soviet-American cooperation over the Korean issue – if it ever existed – was dead.

The Korean War arose out of a complicated milieu; its origins are impossible to reduce down to a single cause. We can safely say, however, that the breakdown in Soviet-American diplomacy, which perpetuated the division of Korea, contributed greatly to the start of the war.

The Soviet Union and its partners in northern Korea boycotted the UN sponsored elections, which were held in May 1948. The Republic of Korea was founded in the south that August, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north in September. Border conflicts broke out almost immediately and the two countries would be at war within two years.

The Soviet-American Joint Commission on Korea is the subject of several postmortems, including one by General A.C. Wedemeyer, and another by Soviet Ambassador Terentii Shtykov, whose diary, obtained by Dr. John Kotch, will be published by the Wilson Center’s History and Public Policy Program in the near future.

The History and Public Policy Program is still working to release more than 200 unpublished and untranslated Soviet records from 1945-1946, obtained from the Archives of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. The documents provide considerable insight into the Soviet Civil Administration, Soviet-American negotiations, and the activities of various political groups in northern and southern Korea.