Editor's Note: For further discussion on this topic, see Damien Van Puyvelde's article "French paramilitary actions during the Algerian war of Independence, 1956-1958," appearing in Intelligence and National Security.

The recent controversy surrounding the release of a French government report on the memory of colonization and the Algerian War highlights some of the difficulties France continues to experience with its colonial past. As historian Benjamin Stora notes in the conclusion to this report, acknowledging France’s controversial practices – including the use of torture – is an important step in the effort to come to terms with its colonial past.

In the past few years, a series of documents on French assassinations (homicide or HOMO operations in French intelligence jargon) and sabotage (ARMA operations) have become publicly available at the French National Archives. These documents, released on the Wilson Center’s Digital Archive and translated in English for the first time, provide a unique evidence base to study the role of French paramilitary actions in the context of the Algerian War of Independence.

Histories of French intelligence provide relatively detailed accounts of the use of paramilitary actions to target Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) and its networks – though they are largely based on unreliable memoirs and oral history interviews. In her excellent research on the Algerian War, historian Mathilde von Bülow identified a broader evidence trail linking French intelligence to a series of paramilitary and political influence operations against the FLN. However, these accounts could not find the proverbial smoking gun in the national archives.

The release of two documents, which can be found in the papers of presidential adviser Jacques Foccart at the French National Archives, now clearly establishes French responsibility for a series of controversial paramilitary operations. These covert actions were more than likely conducted by Service Action, the paramilitary branch of France’s foreign intelligence service (the Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage or SDECE).

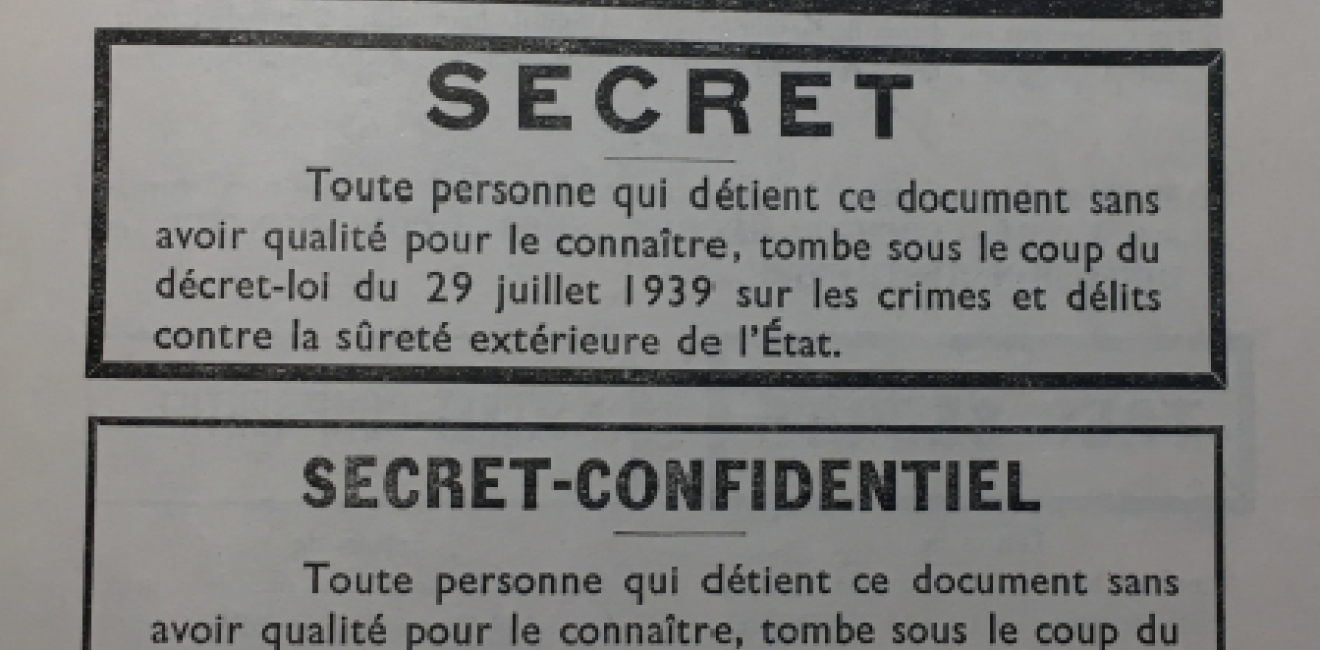

The legacies of resistance and colonial violence provided a toxic heritage that shaped French intelligence practices in the post-war era. These documents – which are unmarked and therefore should remain easily accessible to the public – provide a unique opportunity to expand the body of research on French state and colonial violence and broaden the study of covert action, which has largely focused on the American, British and Soviet experiences.

The first document – which has already generated some media coverage in France – is a SDECE note that designates a target for assassination (Schulz Lesum, a German national who ran a desertion support network for French legionnaires), the means to eliminate this target (an undetectable poison) and – most interestingly – the authorization procedure. The Chief of Staff for the Army, General Paul Ely, proposed to the SDECE to eliminate this individual. This proposal was sent to Presidential adviser Jacques Foccart whose handwritten annotation on the document reads “received on 3 August 1958, have given agreement in principle,” followed by “agreement from Admiral Cabanier [then Chief of Defence Staff] on 4 August” and “forwarded to Col Roussillat [head of the Service Action of the SDECE] on 5 August.”

In sum, the document shows that the operation received political authorization from Presidential adviser Foccart (who had direct access to and can be assumed to write on behalf of President du Conseil de Gaulle) before it was approved by the highest military authority in the country.

The second document is a table synthesizing information on 38 operations conducted or cancelled from January 1956 to March 1958, as well as nine additional operations that were “in preparation” at the time (bringing the total to 47 operations). This table is undated but was probably sent to Jacques Foccart in the summer of 1958, as a part of a broader effort to review French intelligence practices. A redacted and partial copy of this document was displayed at an exhibition at the musée de l’Armée a few years ago, and extracts have recently been shared by French journalist Vincent Nouzille. This unredacted and complete copy reveals the names of the targets, including that of Egyptian President Nasser (an operation that was “cancelled by superior order”). This cancellation and others suggest that French authorities ruled out the assassination of high-level political figures.

The internal evaluation of the operations (last column in the table) shows the inherently subjective nature of assessing the “results” of covert actions. The yardstick used to measure success is strictly operational but debatable nonetheless. Two homicide operations deemed to be “partial” successes killed the mother of the target (instead of the target, arms dealer Otto Schlüter) and hit the family of Dr. Tonnelot, who had provided support to FLN sympathizers. Two other partial successes involved homicide operations that injured but did not eliminate their target. One hypothesis is that – despite missing their objectives – these operations successfully disrupted some of the FLN support networks and publicly signaled that FLN supporters risked their lives (a form of dissuasion). In another case, an operation that did not lead to tangible outcomes (because targets never showed up) was similarly reported as a partial success. The table thus reveals how the uncertain nature of paramilitary actions creates space for multiple interpretations of their results to coexist.

More generally, these two documents confirm France’s extensive use of paramilitary actions in the context of decolonization. As my forthcoming article on the topic will argue, this set of covert practices - inherited from the Second World War - added to the broader range of civilian and military options used by French authorities to maintain influence and project power at the end of Empire.