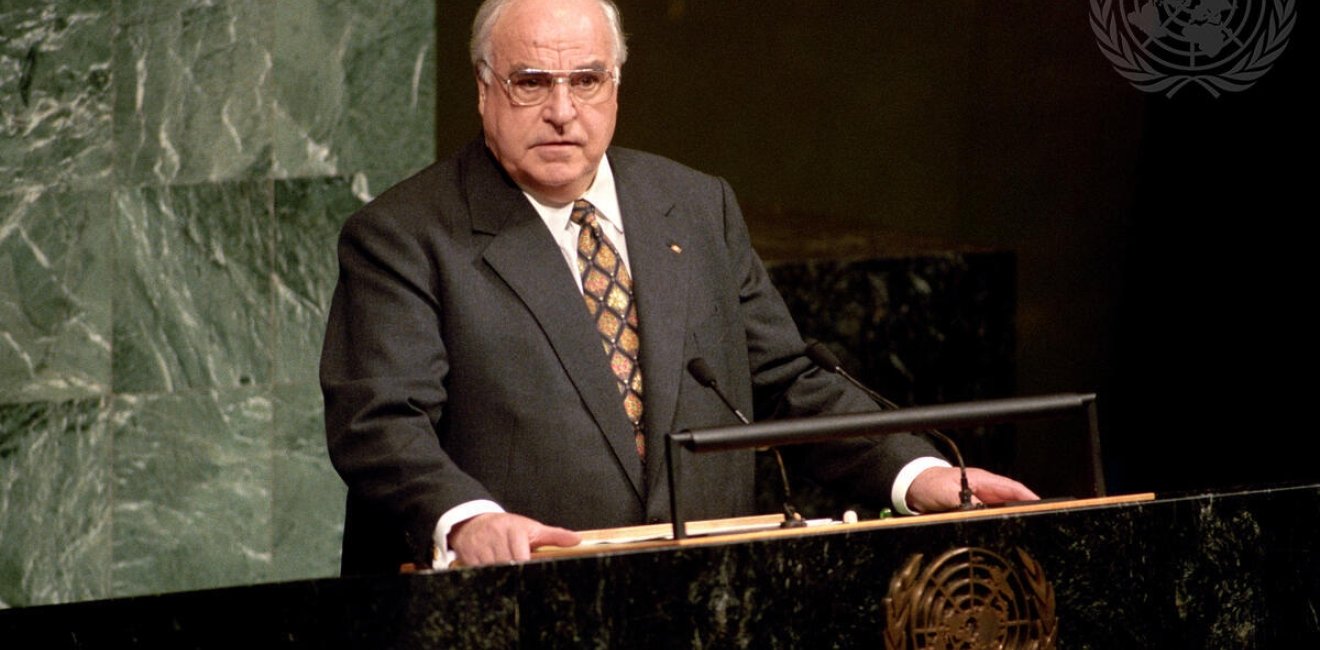

The Helmut Kohl Transcripts: The War in Bosnia and Kohl’s Search for a “Normal” German Foreign Policy

The Bosnia War was a test case for the emergence of a more proactive, militarily invested German foreign policy

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

The Bosnia War was a test case for the emergence of a more proactive, militarily invested German foreign policy

Due to the traumas of two world wars and the horrors of the Nazi period, West Germany’s foreign policy doctrine during the Cold War period focused on preventing military conflict and not engaging in any military conflict. A key importer of security, West Germany emerged as one of the foremost beneficiaries of NATO's collective defense initiatives.

Following unification and the dissolution of bipolar conflict, numerous German leaders hesitated to change the pacifist elements ingrained in German foreign policy, despite the seismic shifts in the global landscape. Chancellor Helmut Kohl, however, discerned the necessity for Germany to embrace a more "normal" foreign policy stance. He advocated for Germany to assert a military presence commensurate with its economic and political stature on the international stage. However, united Germany was only at the beginning of a process of geopolitical maturation. The majority of Germans were apprehensive of the notion that democracies should have the capacity and the political will to use of military force to preserve stability and defend principles of international law.

Being a historian and having lived through World War II, Kohl believed that it would require a considerable amount of time for Germans to overcome their apathy towards military matters. “There was of course fear amongst the populace albeit there were bizarre anxieties. The Germans had a peculiar relationship to war...Nearly every German family had suffered death in the war – and even the younger generation recalled the aches of war from stories,” Kohl noted in one meeting with British Prime Minister John Major.

Under Kohl’s watch, post-Cold War Germany went through a difficult transition as it adopted a more pragmatic attitude toward military power. In 1991, the Kohl government kept Germany out of the military operations in the Gulf War, referring to constitutional restrictions that made out-of-area operations impossible. And yet, Kohl believed that as a mature member of the international community, united Germany had to carry more responsibility. “It was unacceptable for Germany if its contribution to global peace merely consisted of financial donations.”

The Bosnia War was a test case for the emergence of a more proactive, militarily invested German foreign policy. But was united Germany able and willing to come of age? Could it turn from an importer to exporter of security? The stakes were high.

The bloodshed in the former Yugoslavia war had the potential to destroy the kind of integrated Europe that Helmut Kohl was trying to establish. It represented the dangers of fragmentation, ethnic violence, and a potential return to authoritarianism. Moreover, the conflict revived anxieties about a return of great power competition in the Balkans.

At the outset of the war, Kohl and Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher welcomed Slovenia’s and Croatia’s aspirations for independence as the principle of self-determination had also been the leitmotiv for Germany’s unification. In 1991, the Kohl government’s quest for Slovenia’s and Croatia’s recognition caused a fundamental conflict with France and Great Britain. Kohl worked hard to bridge these gaps, warning Slovenia’s President Milan Kucan that “history was again catching up to the peoples of Europe – old receipts from the beginning of the century were again being presented.”

In September 1991, Kohl told French President Francois Mitterrand that “the main problem with regards to Yugoslavia was no longer the right for self-determination but solidarity within the EC. If the EC’s solidarity broke over Yugoslavia two months prior to the concluding conference on the political union [in Maastricht], this would render useless all initiatives toward the political union.”

In turn, Mitterrand complained that the German press was creating an atmosphere resembling the spirit of 1914 and the start of World War I. “If you let things go, one was approaching a dangerous rift running the danger to have a similar psychological situation as back then.”

The Bosnian war challenged the notion that Europe had become a supranational society. The EU was able to find consensus on all kinds of technical details in the economic realm, but it was not yet ready to tackle fundamental security issues, particularly when America was preoccupied by the 1992 presidential elections. Kohl and Mitterrand thought that the use of military force was not an option to end the war. Mitterrand believed “they could pursue very limited military objectives at most. Extended operations would be highly precarious and involved the risk of a second Vietnam....At most, only a very limited operation could be risked, but under no circumstance could the war be expanded. Essentially, the only methods remaining involved economic and political sanctions.”

Things changed when NATO launched Operation Deny Flight in April 1993 to enforce the establishment of the United Nations’ no-fly zone over Bosnia and Herzegovina. US Secretary of State Warren Christopher said that the Clinton Administration “understood Germany’s constitutional problems with regard to a potential military engagement on the territory of former Yugoslavia. At the same time, President Clinton thought that Germany had to play a pivotal role in the process. Hence, mutual consultations were important.”

Germany’s Constitutional Court ruled that German air crews were allowed to work aboard AWACS radar and surveillance planes enforcing the no-fly zone. It was a landmark decision that paved the way for Germany’s first participation in a combat mission out of area.

Finally, Kohl’s vision for a more proactive, militarily invested foreign policy had begun to take shape.

Kohl and Mitterrand discuss the situation in Yugoslavia and Northern Africa as well as NATO and European security.

Kohl and Perez de Cuellar discuss Germany's international role, European integration, the Yugoslavia War, the Middle East and the end of Perez de Cuellar's tenure as UN Secretary General.

Kohl and Gorbachev confer on the state of reforms in the Soviet Union, Western financial assistance and preparations for Gorbachev's participation in the World Economic Summit in London later in July. In addition, they discuss European security, EC enlargement, the potential enlargement of NATO, and the situation in Yugoslavia.

Kohl and Tudjman assess the chances for a peaceful resolution of the Yugoslav crisis and the implications of Slovenia's independence for Croatia's security.

Kohl and Peterle analyze the situation in Yugoslavia and Milosevic's alleged readiness to allow for Slovenia's independence. Kohl emphasizes that it was out of the question for the Federal Republic to recognize Slovenia and Croatia at this points in time as the FRG did not want to abandon the EC consensus prior to the Maastricht Summit.

Antall reports about the ensuring war in Yugoslavia close to the border to Hungary emphasizing his concern of a spillover. He reports about tens of thousands of refugees from Western Croatia.

Kohl and Delors examine the role of the European Community in the stabilization of the Soviet Union's economy including financial aid, as well as in relationship to the conflict in Yugoslavia.

Kohl and Gonzalez discuss the potential for European integration after Germany's unification and the urge for fast action after the coup in Moscow. They review the ensuing war in Yugoslavia and the need for the Federal Republic to avoid going it alone in its efforts for the recognition of Slovenia and Croatia.

Kohl and Mitterrand explore ideas for the creation of a NATO-WEU-European pillar in cooperation with the Bush Administration. Moreover, they discuss the war in Yugoslavia and Franco-German differences which Mitterrand even compares to the situation prior to World War I in 1914.

Kohl and Separovic examine the situation in Croatia against the backdrop of the fact that the Yugoslavian People's Army was just 30km away from Zagreb. Separovic asks for assistance and international recognition.

Kohl and Andreotti elaborate on the timing of Slovenia's and Croatia's recognition. Due to the lack of consensus on this within the EC, they agree to go ahead with a group of five or six countries recognizing Slovenia and Croatia. Both emphasize the need to avoid a repetition of the 1941 World War II coalition in this regard.

Kohl and Kucan discuss the disintegration of Yugoslavia and emphasize the need for minority rights, self-determination and the non-use of force. Kohl explains his position arguing that Germany must not be "singularized" in its diplomacy.

Kohl and Bush talk about the NATO summit, the creation of a European pillar in NATO, the war in Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union's disintegration.

Kohl and Gonzalez discuss the implications of the Yugoslav War on the cohesion of the European Community. Both have a shared concern that the EC could be torn apart. Eventually, they discuss preparations for the European Council in Maastricht in December 1991.

Kohl and Izetbegovic discuss the Yugoslav War, EC sanctions, the potential extension of the war including Bosnia-Hercegovina as well as ideas for a "Marshall Plan" after the end of the war.

Kohl and Kucan debate plans for Germany's recognition of Slovenia prior to Christmas, but not before the convocation of the EC Ministerial Council in Maastricht in order to avoid public debate within the EC. Kohl reiterates his willingness to bring Mitterrand around on this issue.

Kohl and Tudman examine the situation in the Yugoslav War and the state of EC sanctions against Yugoslavia. They discuss Germany's forthcoming recognition of Croatia. In addition, they review the correlation of military forces between Croatia and the Yugoslavian People's Army.

Hartman and Szent-Ivanyi review Hungary's desire for EU membership until the year 2000. Both agree on the necessity for further interim steps in this process. They also discuss Hungary's potential NATO membership and the precarious state of Hungary's security given the war in Yugoslavia.

Mitterrand emphasizes that Yugoslavia could turn into "a second Vietnam” in case of a Western military intervention. He questions the rational of U.S. and British policy in the Balkans and rejects France's military involvement. Kohl rules out Germany's participation in military operations.

Meeting between ChefBK Bohl and Secretary of Defense Cheney on 22 October 1992, 9:40-10:40 Hours

Bohl and Cheney assess the impact of the Yugoslavia war. Bohl emphasizes that lack of the EC consensus on fundamental security issues in contrast to its ability to regulate questions of trade and finance. He argues that this could do massive harm to the European integration project in general. Moreover, Bohl and Cheney discuss German domestic problems with NATO out-of-area missions.

Kohl and Panic review the situation in Yugoslavia and Panic's standing in the domestic struggle with Milosevic. Panic emphasizes his readiness to recognize Slovenia and Croatia reiterating that a democratic Yugoslavia could be a catalyst for peace in the entire region. Kohl remains doubtful arguing that Milosevic would not support such a policy.

Kohl and Ghali discuss Germany's international position after unification and the end of the Cold War. Kohl argues that many were surprised by the return of "old demons" in former Yugoslavia. He emphasizes the long-term objective of establish a new sort of European crisis management excluding a repetition of violent conflicts. This was the rational for his strong engagement in favor of the Maastricht Treaty.

Mitterrand reports on his first meeting with Clinton in Washington and informs Kohl of his forthcoming meeting with Milosevic in Paris. Moreover, Kohl and Mitterrand discuss the current situation in Russia against the backdrop of the country's constitutional crisis.

Kohl and Mitterrand review the latter's meeting with Milosevic in Paris and the lack of results in the French dialogue with the Serbian leadership.

Kohl and Mitterrand discuss NATO's surprising decision to call for Turkish fighter aircraft in the mission to control Bosnia-Hercegovina's airspace. Both criticize the fact that the decision was taken by the military without political consultations. Both Kohl and Mitterrand believe that "this was to wrong way to bring back Turkey to the Balkans."

Kohl and Christopher discuss various scenarios in the search for peace in former Yugoslavia after the failure of the Vance/Owen plan. They debate whether Russia would perhaps accept a lifting of the arms embargo for the Muslims in Bosnia. Moreover, they discuss the state of Germany's domestic debate on out-of-area missions.

Kohl's request for Yeltsin is to put more political pressure on the Bosnian Serbs.

Kohl and Clinton review the state of NATO enlargement after the January 1994 NATO Summit in Brussels. They view NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) as the best solution to engage Russia and to reach out to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Both view the situation in Ukraine as a key factor in the search for Europe's post-Cold War order. "If anything happened in Ukraine, this would increase the pressure for the NATO accession of the Central and Eastern European countries," Clinton says.

Kohl and Major discuss the situation in former Yugoslavia and the need to draw a red line to stop Serbian attacks in the Bosnian war. Both emphasize a potential change in NATO's posture moving from a a peace keeping operation toward a peace enforcing position entailing the possibility of full-fledged war against the Bosnian Serbs.

Kohl and Bildt analyze the situation in former Yugoslavia and agree that the key NATO states were not willing to start a war including hundreds of thousands of soldiers. Kohl says it was out the question for him to send German soldiers waging war in the Balkans.

Kohl wants Yeltsin to pressure the Bosnian Serbs into concession. Kohl's request for Yeltsin is to become engaged personally in such an effort.

Kohl and Major discuss the impact of the war in former Yugoslavia on the Muslim world, the European Community and domestic U.S. policy. Both agree that there was a window of opportunity for a settlement before the winter.

Kohl emphasizes the need for a peaceful liberation of Eastern Croatia. Kohl urgently asks Tudjman to look into Croatian war crimes and human rights violations himself. Kohl wants Tudjman "to enforce discipline in the cases where the allegations were justified and penalize the people that had committed crimes."

Kohl and Rafsanjani discuss the relevance of Bosnia and Hercegovina as a key issue for the Muslim world. In addition, they talk about a new major German credit for Iran.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more