Historicizing the Hegemonic Nuclear Order

Alva Myrdal’s “New Roads to Disarmament" (1967) amounted to an early critique of – and alternative to – what we now call the hegemonic nuclear order.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Alva Myrdal’s “New Roads to Disarmament" (1967) amounted to an early critique of – and alternative to – what we now call the hegemonic nuclear order.

The “hegemonic nuclear order” is an often used descriptor for our current state of nuclear affairs: a limited few countries are allowed to possess nuclear weapons, and the long-term promises of these nations to disarm their nuclear arsenals have not yet been fulfilled.

Although this specific phrasing is relatively new, criticisms of the hegemonic nuclear order are not. Indeed, histories of the hegemonic nuclear order – even those produced prior to the opening for signature of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) – have often departed from or even challenged the narratives of those select few states who benefit from it. In this piece we discuss Alva Myrdal’s “New Roads to Disarmament,” an unpublished paper presented at the Institute of International Affairs in Warsaw, Belgrade, and Zagreb in 1967, which proposed a bold approach to the problems of nuclear weapons in a hierarchical world order.

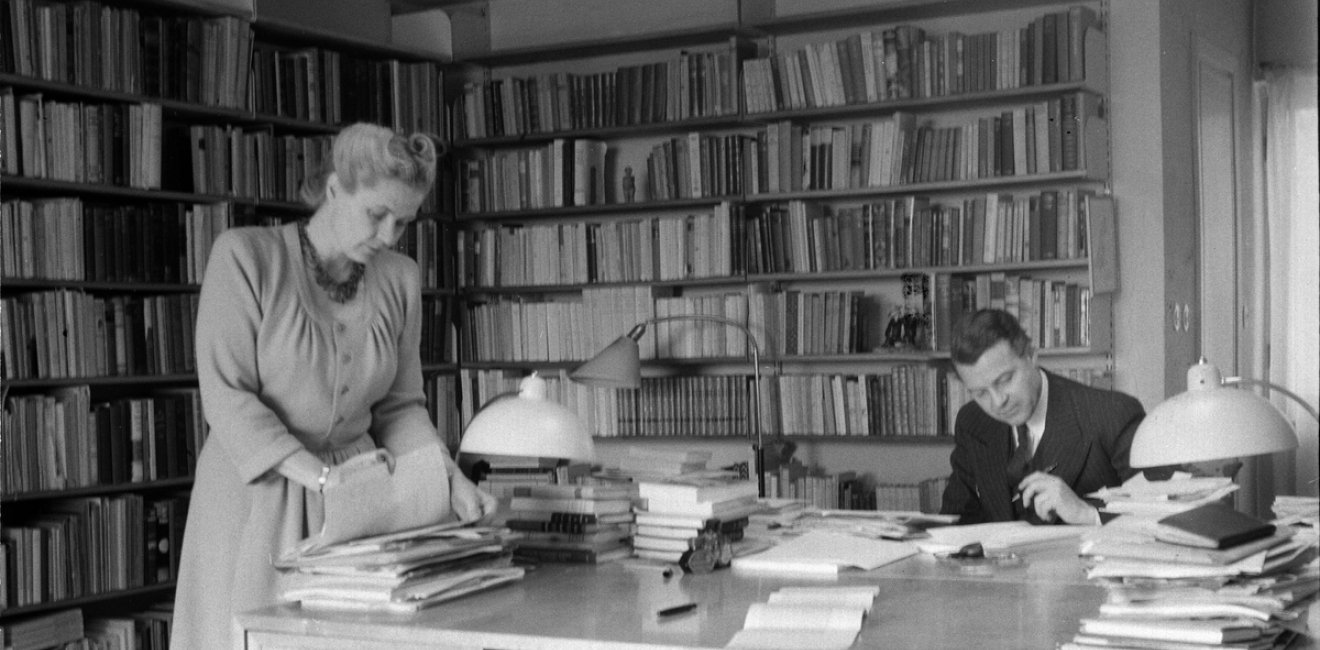

“New Roads to Disarmament” amounted to an early critique of – and alternative to – what we now call the hegemonic nuclear order. Myrdal was head of Swedish disarmament policy from 1962 to 1973. In her 1967 paper, Myrdal positions nuclear disarmament in its broader context and elaborates on her visions of a new world order. She would publicize many of these same thoughts and observations in her 1976 book, The Game of Disarmament. How the United States and Russia Run the Arms Race. In 1982, she received the Nobel Peace Prize for her work on disarmament.

The division between the “haves” and the “have nots” was a core feature of the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, the central pillar of the contemporary nuclear order. While the inability of the nuclear haves to disarm their nuclear arsenals has been criticized by academics, policy makers, and activists alike – and paved the way for the successful conclusion of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) in 2017 – the discriminatory character of the NPT was strongly criticized before the treaty was even opened for signature.

Numerous states, not least many among the eight non-aligned and neutral members of the Eighteen Nations Disarmament Committee, recognized that the treaty under negotiation benefited those states already in possession of nuclear weapons. In 1966, as Sweden’s chief negotiator, Alva Myrdal said:

“I believe that we must be much clearer as to what the arguments really are why a non-proliferation treaty should endeavor to cancel the nuclear option just for states which at present are non-nuclear. If there is to be something of an eleventh commandment: Thou shalst not carry nuclear weapons—why should it only be valid for some?”

According to Myrdal, the draft treaty would lead to a nuclear monopoly, which was by no means uncontroversial. Furthermore, she frequently stressed that additional steps for disarmament were both urgent and necessary.

In “New Roads to Disarmament,” Myrdal elaborated on her ideas about the treaty under negotiation and about alternative routes. Recognizing that nothing more than “modest dimensions” were likely to be accepted by powerful states, Myrdal emphasized the need to “keep open the perspective towards wider horizons.” According to her, the military, economic, political, and cultural hegemony of the great powers “must belong to the bygones that are forever bygones.”

Myrdal, who represented a country that had the technical capacity to develop nuclear arms, questioned why some states were allowed to have nuclear weapons while others were not. Arguing that the nuclear weapon states would have to give up something in return for states like Sweden to guarantee their nuclear weapon-free status in the future, Myrdal called for additional undertakings by the so-called “nuclear-weapon states.” By doing so, Myrdal was an early skeptic of the NPT’s discriminatory essence.

According to Myrdal, a comprehensive test ban treaty (CTBT) and a fissile material cut off treaty (FMCT) would halt both the spread of nuclear weapons and the superpower nuclear arms race:

“And it is a conviction that needs no dispute, that the test-ban as well as the cut-off would effectively stop the have-nots from starting nuclear weapon production. At the same time they would have involved mutual obligations on the part on the nuclear-weapon countries, thus effectively halting the arms race and improving beyond comparisons the climate of confidence in our world’s future. It remains a riddle for me why the Great Powers have chosen the strategy of giving priority to such an ineffective measure as a non-proliferation pledge, particularly as it draws the thunder of political criticism over their heads.”

In various phrasings, the Swedish disarmament delegation proposed a package-deal solution composed of the NPT, a CTBT, and an FMCT as a more balanced alternative than a non-proliferation treaty alone. Myrdal described ongoing efforts to stop the spread of atomic weaponry as reinforcing the position of the nuclear club in world affairs. According to her, this would only benefit the powerful few by increasing their power in relation to the nuclear weapon-free states. Committing to a CTBT as a first step would, according to Myrdal, make the undertakings more equally distributed: “In order to diminish the discrimination I have so often referred to, the super-powers would really be most advised to agree on a test-ban.”

A closer look at Myrdal’s “New Roads to Disarmament” speech from 1967 thus reveals her skepticism – even before the NPT was finalized – toward the discriminatory nuclear monopoly that the treaty would institutionalize. With all cards in hand, and in a present where nuclear weapons still pose a serious threat to human survival, the NPT remains vulnerable to criticism for sustaining a discriminatory hegemonic nuclear order—an order that is additionally undermined by its racialized and sexualized underpinnings.

While the non-proliferation dimension of the NPT has been fairly successful, the nuclear-weapon states have ignored their commitments to disarmament under Article VI of the treaty. Whether that means the treaty that sustains the founding principles of the present nuclear order should be replaced with something more transformative remains a topic in need of further scrutiny and discussion.

This blog post forms part of a project on the constitutional history of the NPT funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more