History, Strategy, and the Imperative of Declassification

Richard Immerman writes that national security is at stake when historians do not have access to the best evidence: declassified government records.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Richard Immerman writes that national security is at stake when historians do not have access to the best evidence: declassified government records.

Strategic planning is very difficult. There are so many variables to consider, ranging from weapons systems, to intelligence estimates, to the risks and opportunities of negotiations, to financial capacity, to available instruments of both hard and soft power, to, of course, short- and long-term goals. The list is almost endless, and it grows longer in every era. Strategic planners warrant our deepest respect.

They also warrant our help, and by this I mean the help of scholars. You might well ask what contribution a scholar, especially a historian, can make to strategic planning. The obvious answer is for us to do what we do best—produce studies of the past that are relevant to today’s challenges. For this purpose of creating a usable past, however, those studies, must, to borrow the words from the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States series’ mandate, be “thorough, accurate, and reliable.” They cannot achieve that end if the vital documents remain classified.

Of course, many if not all high-level government officials possess the necessary security clearances to access these documents. But they may not; it’s an arduous process. And even should they, the documents will be of limited utility. A document taken out of context, or divorced from the others that surround it, is easily misunderstood and/or misinterpreted. The historian, however, is trained to interrogate that document and incorporate it into an intelligible narrative.

Consequently, both the historian and the declassified document can, and should, contribute vitally to the strategic planning process. Granted, many policymakers and political leaders have neither the time nor the inclination to do much reading. Still, those who do tend to read history. When I was at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), my boss regularly started our daily meetings by announcing the title of the book he had just finished, invariably a work of history, and asking whom in the room wanted to read it. Multiple hands always shot up.

Rarely did the book have a direct bearing on a problem we were wrestling with. But even off-point reading can benefit the strategic planner or intelligence analyst. That’s because the reader gains further exposure to what we call historical sensibility. For the historian, history is not just one damned fact after another. Rather, history is the relationship between those facts, defined broadly. It is the product of the synergies among developments—crises, elections, famines, and more—that often occur across diverse geographic areas, and connections between an assortment of government and non-governmental actors and a spectrum of political, economic, cultural, and other dynamics. Further, the premise of the historical narrative is contingency—a sensitivity to the variables that produce one outcome as opposed to the other. For the strategic planner, these variables can represent leverage points and windows of opportunity as well as threats and conflicts.

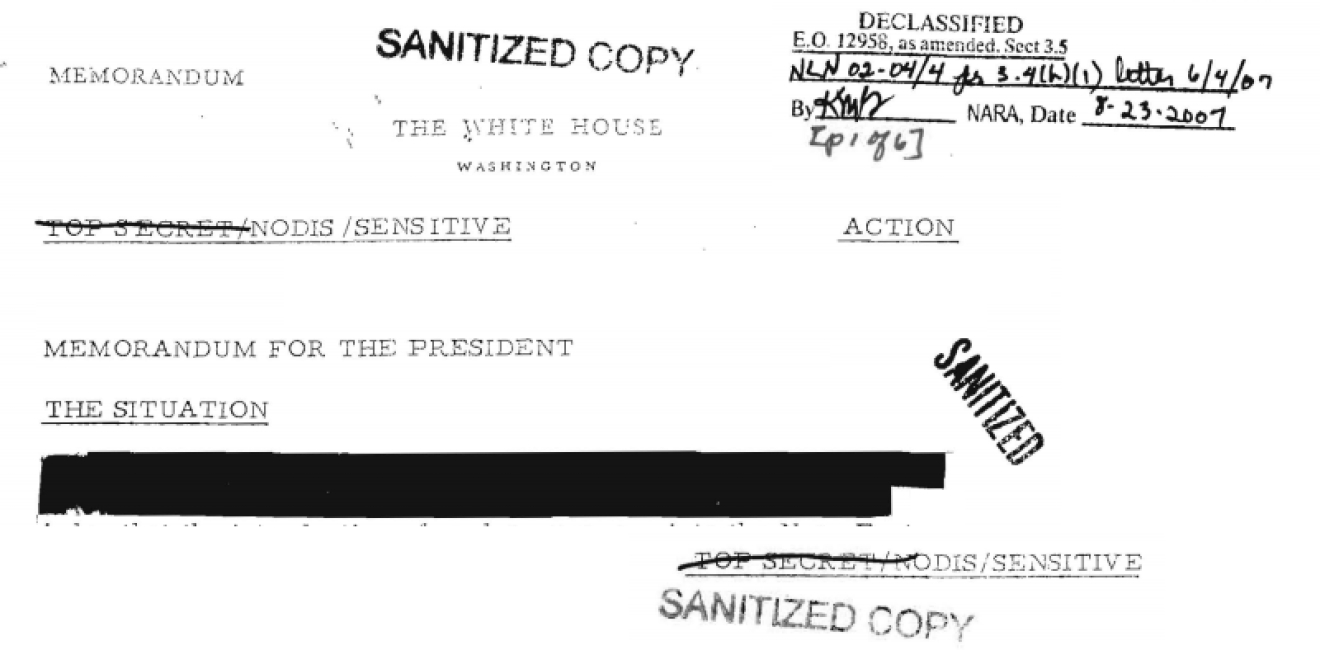

My aim here is not to provide a lesson in the craft of history. Rather, it’s to underscore history’s value to formulating policy and strategy. But to reiterate, that value depends on the quality of the history, which depends on the skill of the historian and the historian’s access to the best evidence. My experience confirms that the best evidence is frequently synonymous with declassified documents.

Let me provide a few examples of what policy planners have learned because of the declassification of evidence. Imagine, to give a familiar illustration, a contemporary official planning to address Iran’s nuclear program without a deep knowledge of America’s part in restoring the Shah in 1953. It took decades to declassify those documents, and even after many became available, the CIA’s role was left unmentioned when the relevant FRUS volume was published in 1989. The uproar generated by that omission led to the 1991 legislation mandating that FRUS must be “though, accurate, reliable” and the decision to redo the volume on Iran. Yet owing to continued battles to declassify the documents, that volume was not published until 2017. And crucial documents remain secret.

I could mention countless other examples, but I’ll focus on nuclear history, including that of nuclear non-proliferation. First, Frank Gavin, who argues (and I’m simplifying) that the orthodoxy on the geopolitical role of nuclear weapons, particularly during the Cold War, exaggerates their influence and portrays that influence as more salutary than is justified; second, Gavin argues that we need not link nuclear proliferation to a march toward Armageddon. I’m not claiming that these arguments are “right.” But they do suggest the complexity of the problem and the need for strategic planners to avoid facile frameworks. What is more, they are based on a firm foundation in the declassified record.

As a second example, no one has contributed more to our understanding of US nuclear strategy than David Rosenberg. By bringing to light America’s massive stockpiling of nuclear weapons early in the Cold war, by underscoring the attention paid to preemption and potentially launching a preventive war, and by uncovering the doctrine of “overkill,” Rosenberg changed our understanding of nuclear planning. He achieved this by declassifying hundreds-and-hundreds of previously inaccessible documents. But what is no less significant for our purposes is that Rosenberg intended to produce a broader study of nuclear and naval strategy through an examination of the career of Arleigh Burke. He didn’t because he couldn’t declassify enough documents. Both scholars and strategic planners are poorer for that.

Adding insult to injury, over the years David also wrote multiple government studies that will almost surely remain classified for decades to come.

On a final note, only by declassifying documents can today’s strategic planners gain essential insight into the varieties of architectures that past planners have used both to receive advice and information and to implement their decisions. Toward this end, explorations of Eisenhower’s project Solarium have gained increasing currency over the past decade. Declassifying those documents was more painful than pulling teeth, and almost 75 years later our success is only partial.

Years ago I attended a conference at which one of the panelists lamented that we historians act as if the purpose of archives is to fulfill our scholarly needs. In fact, much more is at stake—our very national security.

This posting is based on remarks given at an April 23, 2020, virtual workshop on US classification policy sponsored by the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center (NPEC).

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more

The North Korea International Documentation Project serves as an informational clearinghouse on North Korea for the scholarly and policymaking communities, disseminating documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that provide valuable insight into the actions and nature of the North Korean state. Read more