How the GDR Capitalized on the Arab-Israli Conflict

Lorena De Vita explains how East Germany sought to win support from Arab leaders after the Six-Day War.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Lorena De Vita explains how East Germany sought to win support from Arab leaders after the Six-Day War.

The Six-Day War, viewed from East Berlin

News of Arab defeat in the Six-Day War initially came as a blow to the German Democratic Republic. Egypt—an Arab geostrategic partner whose attentions East Germany desired and courted—lost most of its aircraft in just a few hours, having been taken by surprise by the Israeli Aviation Forces (IAF). While at first it seemed that the Arab states could defeat Israel, by the end of the week it became clear that the Arab coalition had suffered another severe loss.

Egypt occupied a special place in the East German political imagination, having been the first country in the region to agree to an economic deal with the GDR, fifteen years earlier. That modest deal then paved the way for a series of other agreements that East Berlin concluded with several countries in the region. This series of timid successes, in turn, fed into East Germany’s eagerness to compete with West Germany, in the Middle East and elsewhere, as an equal.

In the early 1950s, this prospect was little more than an outlandish fantasy on East Berlin’s part, given the disastrous state of its economy. However, being considered a credible commercial partner by Egypt, Libya, Sudan, Syria and others boosted the confidence of the East German establishment; and the slow but steady improvement of the East German economy over the next decade allowed the GDR to augment its presence in the Arab Middle East.

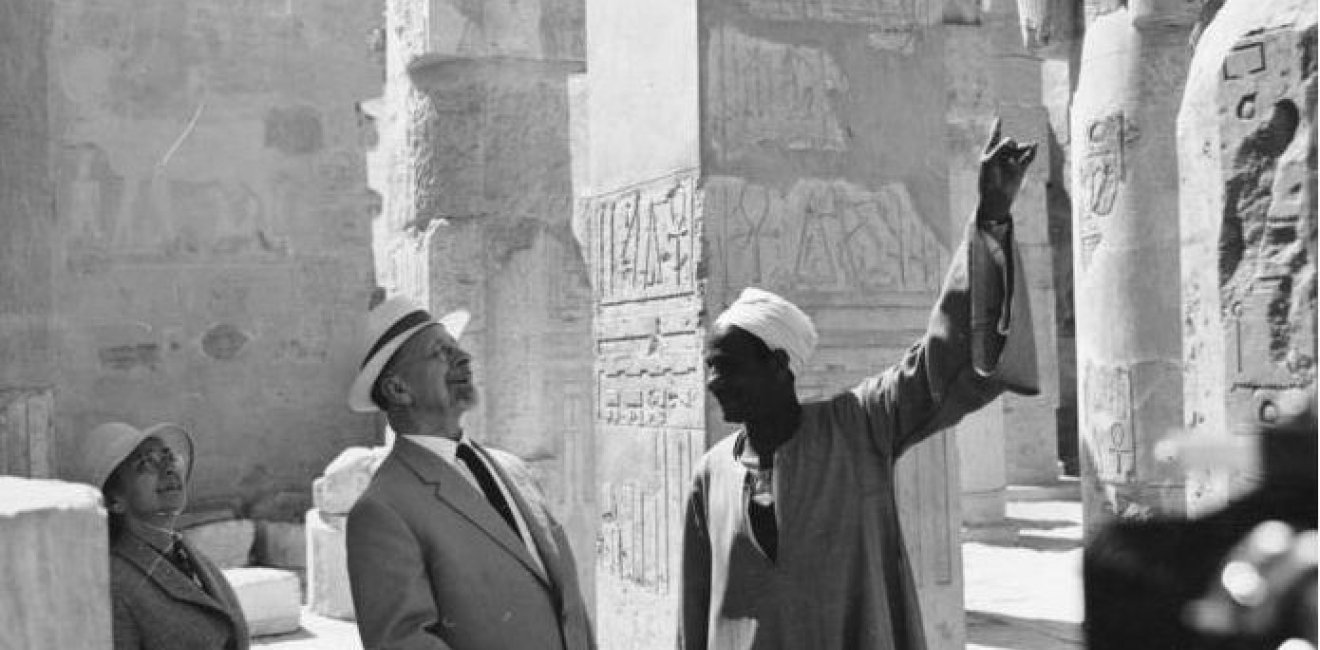

The tougher prize, for the GDR, was getting diplomatic recognition from the Arab states. The East German regime had seemed very close to achieving this goal on several – ever more frequent – occasions: most importantly, when the East German leader, Walter Ulbricht, was invited to visit Egypt in 1965, and was welcomed by Nasser himself; or when, shortly thereafter, six Arab countries broke off relations with West Germany in retaliation for Bonn’s exchange of ambassadors with Israel.

Yet the prospect of gaining diplomatic recognition from the Arab Middle East remained elusive, as the Arab capitals feared that their diplomatic recognition of East Germany would prompt the much more prosperous West Germany to retaliate by cutting off its economic ties to the countries of the region.

Soviet and East German efforts to soothe this fear in the run-up to the Six-Day War seemed to have had little effect. In March 1967, Moscow telegrammed several Arab capitals promising that, in case of their diplomatic recognition of East Germany, the Soviets would step in and counterbalance any resultant economic harm inflicted by West Germany. Two months later, East German Foreign Minister, Otto Winzer, embarked upon a tour of the region, visiting Egypt, Syria, Algeria, Lebanon and Iraq. However, in that case, too, Winzer went back to East Berlin with little to show for his effort. Soviet reassurances seemed to have fallen on deaf ears.

Coming just a few weeks after Winzer’s diplomatic fiasco, the Six-Day War also represented an excellent political opportunity for the GDR – one that could be used to boost East German credentials in the region. The GDR quickly stepped up any level of material support it could give to the Arab states. As war raged in the Middle East, the GDR intensified its deliveries of tanks, jet fighters, and other weapons to the region, as well as sending over pilots, military advisors and medical equipment. The arms deliveries continued well after the war ended, marking a turning point in the GDR’s level of engagement with the region.

The intensified East German-Arab cooperation following the Six-Day War was a great improvement for East Berlin. Just over a decade earlier, during the Suez Crisis, the Soviets under Khrushchev’s leadership had repeatedly discouraged the GDR from reaching out to the countries of the region. Now, with Brezhnev in the Kremlin, the East Germans were finally given the opportunity to show that they, too, could be important geostrategic partners for the countries of the Arab Middle East.

As a letter from Ulbricht to Brezhnev shows, the East German leader was keen to demonstrate to the Soviets how proactive and eager the GDR was in support of the Arab cause, and of the Bloc. In it, Ulbricht called for ‘effective, [Soviet Bloc-] coordinated, fast, political and material support for overcoming the consequences of the [Israeli] aggression,’ which would include ‘solidarity measures towards the Arab countries,’ as well as initiatives to fully exploit the visibility provided by the UN and the other national and international platforms from whence to denounce the Israeli aggressor.

East German support for the Arab cause was in fact not confined to the exchange of material goods only. As usual, in the GDR words were just as important as deeds, and the East German propaganda machine quickly mounted a sustained vicious attack against Israel.

The main thrust of the propaganda campaign revolved around East German leitmotifs. First, Israel was ‘following the tracks of the Hitlerist-fascist aggressors’.[1] Second, the root cause of Israel’s aggression was to be found in Western imperialism, with special blame being attached to West Germany. This was a message East German propaganda had insisted upon since the early 1950s, when West Germany had agreed to pay restitutions (Wiedergumachung/Shilumim) to Israel in the aftermath of the Holocaust, while East Germany had not.[2]

“The connection between … years of extensive supply of tanks and other munitions from West Germany to Israel, and Israel’s aggression, is clear,” denounced the East German Council of Ministers on June 8, 1967 – though neither did most of the weapons used by Israel in the war come from West Germany nor did the later cooperation between the Federal Republic and the Jewish state have anything to do with the post-Holocaust restitutions agreement.[3] Nonetheless, Ulbricht tried to drill the same message into the UAR, Syrian, and Yemeni representatives with whom he met on the same day, contrasting West Germany’s support to Israel, with the ‘total solidarity’ that East Germany devoted to the Arab cause instead. As a 1966 memo of the GDR Foreign Ministry makes clear, vehemently attacking Israel, and emphasizing the close relations between West Germany and Israel, was considered essential to capture the interest of Arab audiences, steering them towards the GDR.

In 1967, therefore, the East German regime did its best to capitalize on the Middle East conflict. Within the Eastern Bloc, the GDR used the Six-Day War to reiterate East Berlin’s loyal commitment to the Soviet superpower, at a time when this was challenged by other junior allies, such as Romania. Indeed, Bucharest had not only gone it alone in January 1967 by establishing diplomatic relations with West Germany (something that was not taken lightly in East Berlin), but in the wake of the war it also refused to follow the Soviet directive to break off relations with Israel.

Within the Middle East, the conflict provided the GDR with the opportunity to support the Arab states to an extent that been impossible for East Berlin until then. In fact, however, East German provisions to the Arab Middle East would remain torn between the ‘willingness and readiness of the GDR to provide assistance’ on the one hand, and the ‘limits of its actual capacities’ on the other, as Stasi officials would put it. Nonetheless, within two years of the Six-Day War, Iraq, Sudan, Syria, South Yemen and Egypt (as well as Cambodia) finally fully recognized the GDR. As the East Germans had by then long understood, there was much to be gained from conflict in the Middle East.

[1] Neues Deutschland, ‘Aufrichtige Freundschaft mit Araberstaaten,’ 12 June 1967, p.1.

[2] Herf, J. Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in the two Germanys (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

[3] The Council of Ministers’ statement was reprinted in Neues Deutschland, ‘Erklärung des Ministerrates der Deutschen Demokratischen Republick zur Aggression Israels,’ 8 June 1967, p.1. On West German-Israeli relations, see Jelinek, Y. Deutschland und Israel 1945-1965: Ein neruotisches Verhältnis (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2004); on the security cooperation see, for example, Shpiro, S. ‘Intelligence Services and Foreign Policy: German-Israeli Intelligence and Military Cooperation,’ German Politics 11:1 (2002), pp. 23-42.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more