India and Flashpoints in Latin America’s Cold War

In India’s Latin American dealings, pragmatism and idealism collided.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

In India’s Latin American dealings, pragmatism and idealism collided.

In India’s Latin American dealings, pragmatism and idealism collide

How did Cold War flashpoints shape India’s relationships with Latin America?

Recent scholarship offers some hypotheses. Historian César Ross claims that the 1954 coup in Guatemala engendered closer relations between India and Guatemala due to New Delhi’s championing of autonomy and democracy. Former Indian Foreign Secretary Krishnan Srinivasan cites “differences” between India and Latin America over the 1973 Chilean coup and the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas War.

Evidence from the Ministry of External Affairs collection at the National Archives of India, however, challenges both of these interpretations.

The paper trail left behind by the Ministry of External Affairs suggests that the “principles” specified by Ross did not determine India’s approach towards the Guatemalan coup. India’s posture towards the Chilean coup and the Falklands/Malvinas War, moreover, aligned with that of many Latin American nations.

In June 1954, US-backed Guatemalan rebel forces overthrew Guatemala’s democratically elected President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. Ross argues:

According to its principles, India gave strong support to [Latin American] countries which saw their autonomy, independence, and democracy threatened… Thus, after [the] US intervention in Guatemala in 1954, India strongly supported Guatemala, which helps explain why Guatemala was one of the countries which most fiercely adhered to India's international agenda in the UN.[1]

Evidence from India’s National Archives challenges Ross’s claims: despite opposition to the US-supported military junta, India still found reason to recognize the new Guatemalan government.

M.A. Husain, India’s Joint Secretary for the Americas Division, did express concern over recognizing a government that had seized power without a constitutional mandate. But lacking formal diplomatic relations with Guatemala or personnel on the ground, Indian officials were confined to American and British versions of events. India learned from British officials in September that the Guatemalan junta was “well established, in complete control of the country, and evidently anxious to adopt a progressive and democratic policy.” Husain limply concluded that, “This view may, perhaps, be accepted at its face value.”[2] If anything, Husain took comfort in the fact that the US “seems determined to ensure the safety of the new regime.”[3]

Other considerations also appeared important to India. Husain hoped that recognition of the emerging Guatemalan regime would lead Guatemala to support future Indian initiatives at the United Nations.[4]

G.J. Malik, India’s charge d’affaires in Buenos Aires, argued that India’s traditional policy of waiting to recognize a government until it had proven itself “stable” was ill advised for Latin America “because then some countries might be permanently without recognition!” As evidence, Malik claimed that the average duration of Bolivia’s government since independence had been less than one year.[5]

Most important, India did not feel “strongly” about the Guatemalan coup. Husain concluded that recognition was no more than “a matter of academic importance” given that India and Guatemala had not established formal diplomatic relations and possessed “no problems of especial importance whose solution had to be sought by special negotiations.”[6] India recognized Guatemala’s military junta in 1955, but India and Guatemala did not establish formal diplomatic relations until the 1970s.[7]

Srinivasan argues that “differences with the [Latin American] region arose from India’s equivocal stand on the Falklands in 1982 and its ambivalence over Pinochet’s coup in Chile” in 1973. Srinivasan fails to delineate these “differences,” their ramifications, or their origins. In fact, archival evidence suggests that India’s posture toward both regional crises aligned with that of many Latin American nations.

On September 11, 1973, Chilean military officers—led by Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army Augusto Pinochet—overthrew democratically elected President Salvador Allende. India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Foreign Minister Swaran Singh condemned the coup and the erosion of democracy in Chile.[8] Gandhi even warned of “big external forces” combining with “internal vested interests” to produce a similar coup in India.[9] Malik, India’s Ambassador to Chile, expressed shock at the human rights abuses committed by the Chilean military. Two months after the coup, he wrote that, “It is hard to believe that the well-educated, civilized Chilean army officer… is responsible for all this. Yet, the evidence cannot be denied.”[10] India subsequently withheld de jure recognition of the Chilean government for the remainder of 1973.

But India was unprepared to forego relations with the Pinochet regime. Malik concluded that the “fact that Chilean Junta is behaving with total disregard for human rights should not stand in way of our recognizing them.” Malik reasoned that India could express its disapproval of the Chilean atrocities “by saying publicly that recognition does not imply any kind of moral judgment.” He believed that “recognition may enable us to help some victims of Junta.”[11] An internal note sent from J.S. Teja, Joint Secretary of the Americas Division, to the Lok Sabha Secretariat encapsulated India’s ambiguity toward the coup: “The Government and people of India have deplored the events in Chile… but it is essentially an internal affair of the Chilean people.” Teja hoped that Indo-Chilean relations would be “strengthened in the future.”[12]

By November, India’s public condemnation of Chile and its agreement to handle the diplomatic affairs of the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia in Santiago made India “unpopular” in the eyes of the Pinochet regime.[13] It is certainly possible that other Latin American military dictatorships in favor of the Chilean coup, such as those in Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, felt a similar antipathy towards India. But India’s position did not place it at odds with many key Latin American nations.

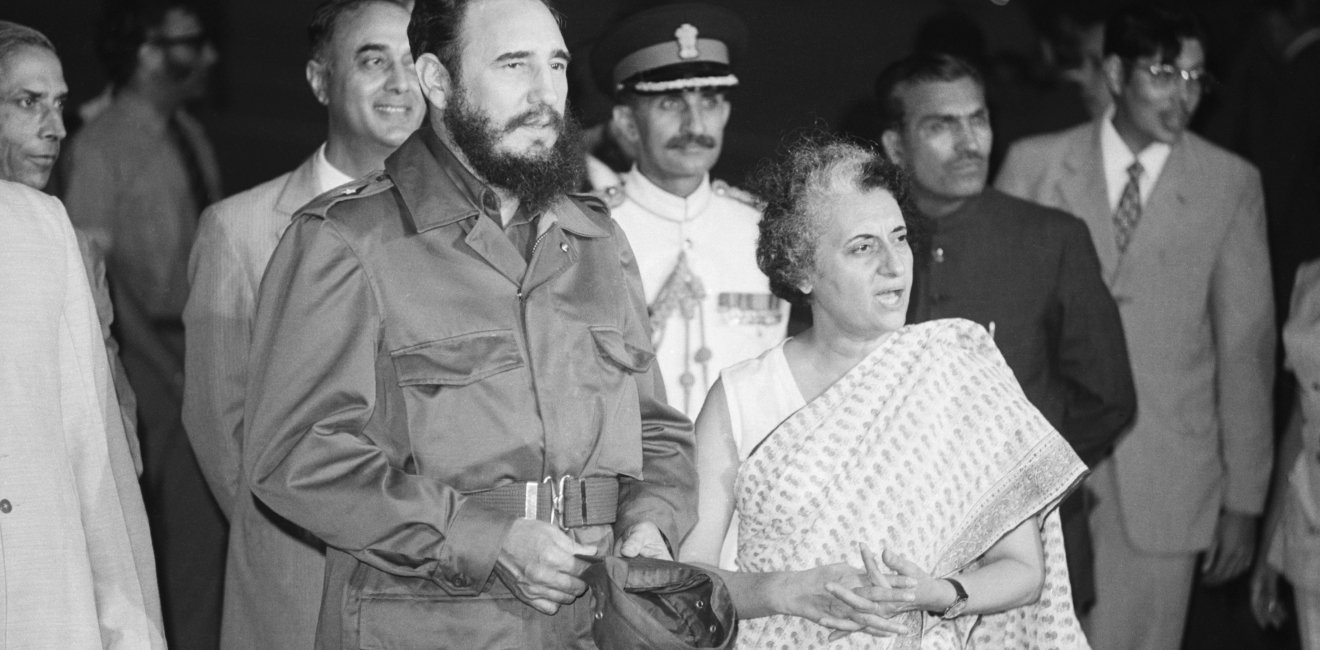

On the day of the coup, Cuban leader Fidel Castro landed in New Delhi and dined with Gandhi. Gandhi toasted Indo-Cuban friendship and Cuban prosperity, after which Castro said, “We offer our sincere friendship and deep sympathy and strongest solidarity in your struggle, in your efforts to overcome underdevelopment.” Six days later, Castro again stopped in New Delhi. On this occasion Gandhi informed Castro that India’s UN delegate would “voice the dangers to developing societies in having the Chilean type of threats to their democratically established regimes,” but that India “would not talk about American involvement as it would unnecessarily strain Indo-American relations.”[14] There does not appear to be any memoranda of these Castro-Gandhi conversations, but neither does there appear any evidence that the Chilean coup altered Indo-Cuban relations.

Meanwhile, Argentina quickly recognized the Pinochet regime, but India’s Ambassador to Argentina M.M. Khurana concluded that it “does not mean that they approve of the coup or the method in which it was undertaken or support the policies of the new government… as neighbors sharing the longest border in the world, they have no other alternative.”[15] If anything, Khurana viewed Allende’s overthrow as a call for India to strengthen its relations with Argentina: “The coup… makes it more important for us to cultivate Argentina because she is now one of the few countries left on the Continent which adhere to the principle of non-alignment and constitute a democratic government based on popular support.”[16]

S.K. Roy, India’s Ambassador to Mexico, agreed. He saw Argentina as “totally isolated” following the Chilean coup, while an “almost equally difficult situation faces Peru” given the socialist policies adopted by its government. Roy concluded that Mexico was also “now virtually isolated.” With the hardline Nixon Administration to the north and US-backed military regimes in Central and South America, the Chilean coup made Mexican President Luis Echeverría “a very worried man indeed.” Like India, Mexico withheld de jure recognition from the Pinochet regime.[17] Finally, Venezuela recognized the Pinochet regime following its policy of “ideological pluralism,” a posture unlikely to condemn India’s position.[18] Overall, India’s cautious approach towards the Chilean coup paralleled that of many Latin American nations.

Archival evidence also challenges Srinivasan’s depiction of the Falklands/Malvinas War. In the spring of 1982, Argentina and Great Britain waged war over the Falklands/Malvinas, South Georgia, and the South Sandwich Islands. While India condemned Argentina’s use of force to retake the islands, it supported Argentine sovereignty over the disputed territory.

India’s Ambassador to Argentina K.F. Ernest believed that Argentina had “been inspired by” India’s equilibrium in international affairs and “admired the fact” that India took an independent stance on the War despite its close ties to Great Britain. Ernest noted that when India was selected to host the seventh Non-Aligned Summit in 1983, Argentina was one of the first nations to respond and declared that its President would lead the Argentine delegation for the first time.[19] Moreover, India’s qualified support for Argentina reflected the general consensus across Latin America (with Chile an important exception).

Evidence presented here challenges previous notions of how flashpoints in Latin America’s Cold War shaped India’s relationship with the region. These documents offer insight into perceptions of Latin America by a key nation of the Global South. Like the CWIHP e-Dossiers by Vanni Pettiná, Thomas C. Field, Jr., and Daniela Spenser, this entry helps to foster a more global understanding of Latin America’s Cold War.

[1] César Ross, “India, Latin America, and the Caribbean During the Cold War,” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, Vol. 56, No. 2 (July/December 2013), 26

[2] Telegram No. D.6151/54-AMS From Joint Secretary of the Americas Division (M.A. Husain) to the Prime Minister (J. Nehru), September 15, 1954, SECRET, S/54/1732/73, NAI, Delhi

[3] Telegram From Joint Secretary of the Americas Division (M.A. Husain) to Foreign Minister (R.K. Nehru), September 9. 1954, SECRET, File No. S/54/1732/73, NAI, Delhi

[4] Telegram No. D.6151/54-AMS From Joint Secretary of the Americas Division (M.A. Husain) to the Prime Minister (J. Nehru), September 15, 1954, SECRET, S/54/1732/73, NAI, Delhi.

[5] Letter F.21-4/54/BA From Charge d’affaires in Buenos Aires (G.J. Malik) to Joint Secretary for the Americas (M.A. Husain), October 13, 1954, SECRET, S/54/1732/73, NAI, Delhi

[6] Telegram No. D.6151/54-AMS From Joint Secretary to the Americas (M.A. Husain) to the Prime Minister (J. Nehru), September 15, 1954, SECRET, S/54/1732/73, NAI, Delhi

[7] N.P. Chaudhary, India’s Latin American Relations (New Delhi, India: South Asian Publishers, 1990): 27

[8] Text of Swaran Singh’s Statement at UN Assembly, Ministry of External Affairs Press Relations Section, October 3, 1973, WII/101/20/73, NAI, Delhi

[9] Letter From Joint Secretary for Public Diplomacy (S.K. Singh) to Indian Delegation in New York, September 17, 1973, SECRET, WII/101/20/73, NAI, Delhi

[10] Telegram No. SANT/101/3/73, From Indian Ambassador to Chile (G.L. Malik) to Secretary of the Western Division (A. Singh), November 22, 1973, SECRET, WII/101/20/73 – Vol. II, NAI, Delhi

[11] Telegram No. 59, Indian Embassy in Santiago (G.J. Malik) to Ministry of External Affairs, November 23, 1973, SECRET AND IMMEDIATE, WII/101/20/73 – Vol. II, NAI, Delhi

[12] Self-Contained Note From Joint Secretary for the Americas Division (J.S. Teja) to the Lok Sabha Secretariat (P.K. Patnaik), December 17, 1973, SECRET, WII/162/26/73, NAI, Delhi

[13] Telegram No. SANT/101/3/73 From India’s Ambassador to Chile (G.J. Malik) to Foreign Secretary (K. Singh), November 16, 1973, WII/101/20/73 – Vol. II, NAI, Delhi

[14] N.P. Chaudhary, India’s Latin American Relations (New Delhi: South Asian Publishers, 1990): 163

[15] In fact, at the time the Argentine-Chilean border was second in length to the U.S.-Canadian border.

[16] Letter No. BUE/101(4)/73 From India’s Ambassador to Argentina (M.M. Khurana) to Secretary for the Western Division (A. Singh), September 20, 1973, SECRET, WII/101/20/73, NAI, Delhi

[17] Letter No. MEX/101/18/73 From India’s Ambassador to Mexico (S.K. Roy) to Joint Secretary for the Americas (J.S. Teja), September 24, 1973, SECRET, WII/101/20/73, NAI, Delhi

[18] Letter No. CAR/104/3/71 From India’s Ambassador to Venezuela (A.R. Kakodkar) to Deputy Secretary for the Americas Division (S.K. Arora), September 21, 1973, WII/101/20/73, NAI, Delhi

[19] Telegram No. BUE/101/1/82 From First Secretary, Embassy of India in Buenos Aires (K.F. Ernest) to Ministry of External Affairs, March 25, 1983, WII/101/54/83, NAI, Delhi

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more