On 7 June 1981, the Israeli Air Force launched a strike against the Iraqi nuclear reactor Osirak, marking it as the first successful raid conducted against a ‘hostile’ nuclear reactor. The raid has received much attention in academic and political circles, especially in the context of the Iranian nuclear program, yet significantly, some important questions on Washington’s reaction to the raid and its impact on Reagan’s nonproliferation policy were left unanswered. We address these questions by exploring declassified documents from numerous archives in a forthcoming article in the Journal of Cold War Studies.[1]

Iraq’s nuclear program made critical progress in 1979 and 1980, with the assistance of nuclear technology imported from France and Italy. In July 1979, US diplomats told their Italian counterparts that it was an “American strong belief” that Iraq was pursuing a nuclear capability.

When Reagan won the November 1980 presidential elections, Iraq’s nuclear program was not on his agenda. His Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA) transition team called for a clean, dramatic break from the policies of the outgoing Carter administration on nuclear proliferation.

On 7 June 1981, the day of the raid, a policy paper composed by the ‘Senior Interagency Group on Nuclear Nonproliferation and Nuclear Cooperation’ (SIG) was submitted to the NSC. The paper crowned the administration’s nonproliferation efforts as a “key foreign policy objective” and called to revise the existing Carter era legislation, the 1978 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act (NNPA).

When the raid took place, it caught the administration by surprise, leading to an initially harsh reaction towards Israel. Secretary of State Alexander Haig told the Israelis that the raid caused a serious complication for the US, stating, “President Reagan thinks the same.” The Israelis learned from Haig and from another source that Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger was promoting a tough, anti-Israel response. The raid was carried out by American F-16 jets and Israel was legally required not to use them to attack its neighbors, unless as an act of “legitimate self-defense. The administration suspended the delivery of additional jets, pending a legal review of the strike. Israeli ambassador to Washington, Ephraim Evron, informed Reagan that Israel was surprised and concerned by the unexpected suspension.

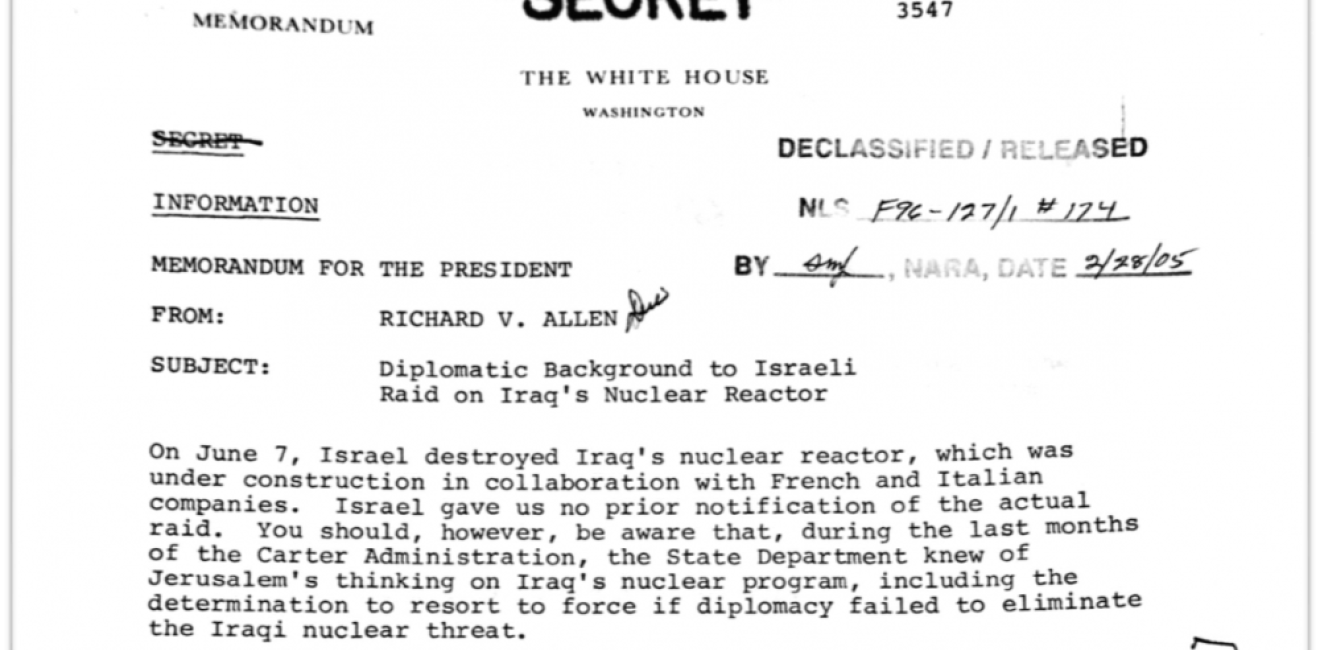

A week after the raid, the US attitude started to change. National Security Advisor Richard V. Allen informed Reagan that the administration was in fact “not required to make a legal determination on whether Israel violated US law,” stating the issue should be treated “as a political rather than a legal question.” Indian diplomats speculated that the suspension was perhaps an American goodwill gesture towards Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, designed to appease him and keep the peace process with him alive.

Administration officials were gradually becoming aware of a “gap” in the administration’s “institutional memory,” as termed by US ambassador to Israel, Sam Lewis. In a diplomatic cable, Lewis explained that the Carter administration had clear indications from Israel on its intention to launch a strike. Realizing that the raid should have been at least somewhat anticipated, the administration now chose to adopt a milder approach.

Within the administration, NSC staffers supported the softest line, stopping short of supporting of the raid. On the other hand, a key, pro-Israeli voice belonged to ACDA Director-Designate Eugene Rostow, who stated that Israel should be given an exemption from the NPT given the dangers of the region.

A few days into the crisis, Haig proposed a new strategy to deal with the raid. According to this strategy, Washington would harshly condemn Israel but would “draw the line on punishment.” Weinberger adhered to his support of a punitive response, voicing his criticism of the Israeli leadership in other unrelated instances in the months to come.

The diplomatic battle spilled over into the IAEA. Israel publicly criticized the agency for its shortcomings in Iraq, while agency officials staged their own counter campaign. In September 1981, the US delegation to the agency’s General Conference (GC) was instructed to anticipate a “severe attack” against Israel, and to “vigorously” object to a vote on the “suspension of technical aid” to Israel. In September 1982, as the diplomatic conflict continued, the delegation was ordered to leave the IAEA’s building, thus withdrawing from the agency, in a response to a vote rejecting the credentials of the Israeli delegation.

In Congress, the administration criticized the agency, raising “questions” on the “credibility and reliability” of its safeguards.[2] But the withdrawal was short-lived and Washington resumed full participation in the agency in February 1983, once Israel’s status was clarified. The administration explained this by underlining the agency’s critical role, and the lack of alternatives for its safeguards system.[3]

Our study underscores the hierarchy of goals within the administration’s foreign policy in the wake of the Osirak air raid. Notably, nonproliferation concerns had a shaky, yet steady, place, as the administration adopted an improvised, cautious approach to non-proliferation, rather than a well-ordered strategy. After some wrangling, Washington ostensibly worked to preserve the existing nonproliferation regime, seen as the only credible option at hand, rather than undermine it completely.

[1] Giordana Pulcini and Or Rabinowitz, “An ounce of prevention - a pound of cure? The Reagan Administration’s non-proliferation policy and the Osirak raid”, Journal of Cold War Studies, vol.23, n.2, Spring 2021.

[2] United States Executive Office of the president, “Report to the Congress Pursuant to Section 601 of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Act of 1978: For the Year Ending December 31, 1981.” (1982), p. 23-24, DNSA.

[3] Report to the Congress Pursuant to Section 601 of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Act of 1978: For the Year Ending December 31, 1982.” (January 1983). p. 5. DNSA.