Korean War International History since 1995

William Stueck, the author of "The Korean War: An International History," reflects on the literature surrounding the Korean War that has emerged over the past 25 years.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

William Stueck, the author of "The Korean War: An International History," reflects on the literature surrounding the Korean War that has emerged over the past 25 years.

It has been 25 years since publication of my book The Korean War: An International History. I remarked in the introduction that I was humbled by “the realization of how little I know about the Korean War, of how much remains to be done by those who will follow me.”[i] The passage of time has borne out that thought, as numerous scholars since then have taught me much about the topic. My own subsequent research, focused primarily on the broad history of US-Korean relations, has given me some new perspective. In the text below I will offer a few observations on the literature based on a combination of my own research and that of others. In the citations I will acknowledge some additional contributions without any pretense of mentioning all the works from which I have learned since 1995.[ii]

My most enduring satisfaction with the book is that the basic argument—that, although the conflict was terribly destructive to the Korean people and at one point threatened to expand well beyond the peninsula, it ultimately had a stabilizing impact on the Cold War—has been widely if not universally accepted. In his recent synthesis of the early Cold War, Samuel F. Wells Jr. refrains from counterfactuals, but his argument that Western rearmament was necessary and that the Korean War made it possible is very much in line with my own interpretation.[iii]

As with most syntheses, Wells’ book is less original in its overriding argument and its parts than in the way it combines those parts. To some extent the same could be said of Wada Haruki’s book of the same title as mine. Although Wada’s exceptional linguistic skills provide him with access to a wider range of the original documents than any other scholar, his dense narrative is highly traditional in emphasizing what political leaders and diplomats said to each other. Unlike Wells and me, however, he treats the war as more of a regional than a global event and he provides greater coverage of the war’s impact on Japan while reaching the common conclusion that that country, along with the Nationalist Chinese government on Taiwan, was the conflict’s biggest winner.[iv]

Nonetheless, Wada advances a revisionist interpretation of relations among the three Communist powers involved in the war from the summer of 1952 through early 1953. It has long been understood that by mid-1952 North Korea’s Kim Il Sung wanted to accept the US stand on prisoners-of-war so as to achieve an armistice. Wada does not challenge this view, but he does argue, contrary to most other scholars, that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was on board with Kim’s view while China’s Mao Zedong was not. In making his case Wada provides a detailed analysis of the talks between Stalin and Chinese and North Korean leaders during August and September 1952.[v] If his evidence is far from definitive, his argument serves to emphasize that, first, the Sino-Soviet relationship during the war was highly complex and, second, that much contested terrain still exists among scholars regarding that relationship.

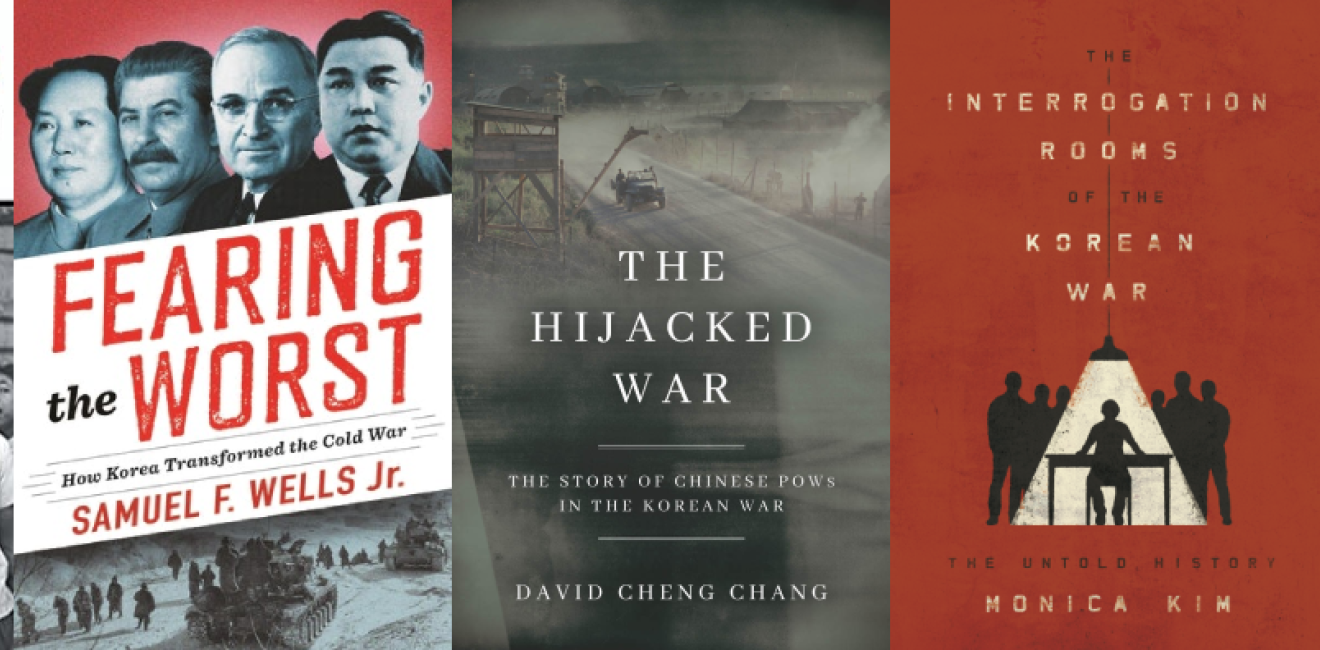

In method and analysis two of the three most innovative books focus on the prisoners-of-war issue. Monica Kim’s The Interrogations Rooms of the Korean War and David Cheng Chang’s The Hijacked War break new ground in both research and analysis.[vi] Kim focuses on Korean prisoners held by the United Nations Command, while Chang concentrates on Chinese prisoners. Kim’s extensive use of postcolonial theory results in some dense and obscure prose, not to mention occasional arguments that stretch her evidence, but her research on three continents, including interviews with former prisoners, and her perceptive accounts of the interaction of interrogators and prisoners offer striking insights into the nature of the war on the ground and the struggle of individuals to negotiate their way through a highly contested postcolonial world.

Chang’s research is at least as impressive as Kim’s and his avoidance of theoretical constructs makes his prose more consistently accessible. His stories of the backgrounds of Chinese POWs and their fates are truly fascinating. His balanced treatment of the two sides in the Chinese civil war is unusual and commendable. Together, these two books demonstrate the promise of integrating social history with the more traditional focus of diplomatic historians on high-level politics.[vii]

Masuda Hajimu’s Cold War Crucible also demonstrates the potential for linking social history with high-level politics. Masuda views the Korean conflict as a critical event in shaping the post-World War II order, both in international and domestic politics. Focusing on the evolution of public perceptions in the United States, China, Japan, and the United Kingdom, and the efforts of governments in those countries to mobilize their populations to fight what was widely thought could become a third world war, Masuda portrays Korea as a seminal event in shaping both international and domestic politics. In my mind he underestimates the degree to which the Cold War had already caught on in the minds of decisionmakers and the public prior to June 1950, but in research and method there can be no doubt that, along with Kim and Chang, he is on the cutting edge of a new generation of scholars determined to integrate traditional subfields in history.[viii]

Alas, I cannot claim that my own research since 1995 has been nearly as pathbreaking, but it has been extraordinarily rewarding. I confess that, when my international history was published, I knew little about Korea. The book, in fact, focused less on the US relationship with the peninsula than the impact of the conflict there on the evolution of the Cold War. So my concentration since then on bilateral relations going back to the late nineteenth century and moving forward to the present has proved to be a very different and rewarding experience. For one thing, the study of a broader time period has given me a keener sense of change and continuity in the relationship. For another, concentration on bilateral interaction has provided a new appreciation of the impact of the Korean War on that relationship. Were I to be offered the opportunity to write a second edition of my international history, I would devote more space to how the war impacted the psychology and mechanics of Korean-American relations and how that development helped set the stage for a durable if sometimes turbulent alliance that has impacted significantly the evolving politics of Northeast Asia.[ix]

Finally, my work has rewarded me with an ongoing relationship with the Woodrow Wilson Center’s international history projects, which continue to facilitate the interaction of scholars across national boundaries. Both my international history and my subsequent work have been much enhanced by the collection and translation of documents by the Wilson Center and by its hosting of numerous workshops, conferences, and critical oral histories. Thank you!

[i] William Stueck, The Korean War: An International History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), p. 9.

[ii] Let me acknowledge several outstanding works that are not mentioned in the text or in subsequent citations. Allan R. Milletts The War for Korea, 1945-1950: A House Burning (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2005), is particularly useful on South Korean politics prior to the North Korean attack in June 1950. Bryan R. Gibby’s The Will to Win: American Military Advisers in Korea, 1946-1953 (Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2012), highlights the impact of US advisers and their South Korean counterparts in building the ROK army, especially during the war. Steven Casey’s Selling the Korean War: Propaganda, Politics, and Public Opinion 1950-1953 (London: Oxford University Press, 2008) breaks new ground on domestic politics and mobilization in the United States, as does Paul Pierpoli’s Truman and Korea: The Political Culture of the Early Cold War (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1999); Sahr Conway-Lanz’s Collateral Damage: Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity after World War II (New York: Routledge, 2006) greatly increases our understanding of the Korean War’s impact on American perceptions of and justifications for the use of air power.

[iii] Samuel F. Wells Jr., Fearing the Worst: How Korea Transformed the Cold War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020). I hasten to add that other scholars have emphasized how the war served to exacerbate conflict in the Third World. I agree, but I also continue to believe that the war made less likely a direct military conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, which in all likelihood would have led to World War III.

[iv] Wada Haruki, The Korean War: An International History (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014), pp. xxvi-xxvii, 299-301.

[v] Ibid., pp. 234-42, 252.

[vi] Monica Kim, The Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War: The Untold History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019); David Cheng Chang, The Hijacked War: The Story of the Chinese POWs in the Korean War (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020).

[vii] Kim does provide a chapter on the American POWs and their return to the United States after the armistice. In his Name, Rank, and Serial Number: Exploiting Korean War Prisoners at Home and Abroad (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), Charles S. Young provides a more extensive account of the American POWs. In Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea (New York: Norton, 2013), Sheila Miyoshi Jager provides a more limited but important analysis of the experiences of American and South Korean prisoners (see pp. 208-36).

[viii] Masuda Hajimu, Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015).

[ix] For my recent work in this area, the first two co-authored with former graduate students of mine, see William Stueck and Boram Yi, “’An Alliance Forged in Blood:’ The American Occupation of Korea, the Korean War, and the US-South Korean Alliance,” Journal of Strategic Studies 33(April 2010): 177-209; Jun Suk Hyun and William Stueck, “The U.S.-ROK Relationship into Full Bloom: From ‘Little Strategic Interest’ to Alliance Partner, 1947-1966,” Journal of American-East Asian Relations 26(Spring 2019): 103-140; and William Stueck, “Ambivalent Occupation: U.S. Armed Forces in Korea, 1953 to the Present,” in Robert A. Wampler (ed.), Trilateralism and Beyond: Great Power Politics and the Korean Security Dilemma During and After the Cold War (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2012), pp. 13-49.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The North Korea International Documentation Project serves as an informational clearinghouse on North Korea for the scholarly and policymaking communities, disseminating documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that provide valuable insight into the actions and nature of the North Korean state. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more