While conducting research at the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN) in the Dominican Republic for my dissertation, I came upon documents that described the torture and death of Reyes Florentino Santana, a black university student, and four of his friends in 1971. Enthralled by my findings, I hurried to the hotel to share it with my mother. Her reaction, however, was very unexpected. As she broke into tears at the sight of the documents, she confessed that Santana had been her first teenage boyfriend, whose death she never overcame.

This archival experience that my mother and I confronted is not at all unique in the Latin American scene. Latin American historians are now realizing that archives have a particular kind of individual resonance that goes beyond academic production. The archival work of Greg Grandin, Kirsten Weld, and Steve Stern, as well as my own burgeoning digital collection, attest to the shifting role of the Latin American archive. For Latin American and Caribbean countries that suffered under the Cold War divide, the archive has shifted from a tool of surveillance and repression to an institution where an individual can find political and personal redemption.

In the case of my mother, who currently serves as research assistant for my dissertation, the archive transformed from a place of secrecy and conspiracy to a place of political interaction and healing. During her days of activism in the Dominican Republic, state institutions represented violence, authoritarianism, and political secrecy. The archive was one of many institutions that reified the sense of being watched and surveilled. It was, for many Dominicans, where the secrets of the state lived. The impotence and frustration of being oblivious to who tortured and murdered her boyfriend remained part of her political experience. The vaulted secrets of that massacre seemed impossible for my mother to ever penetrate. In addition, for many poor brown and black Dominicans like my mother taking the time to do research about a massacre of fifty years ago is practically impossible. Archives, at least in the Dominican Republic, are usually in the posh side of town, limiting most people’s mobility to do research. But now, as the mother of a PhD student from an Ivy League university, research is something she does with me almost every summer. Thus, in her lifetime, the archives shifted from an alienated repository of violence to an uplifting source of emotional retribution. We now know who killed Reyes Santana.

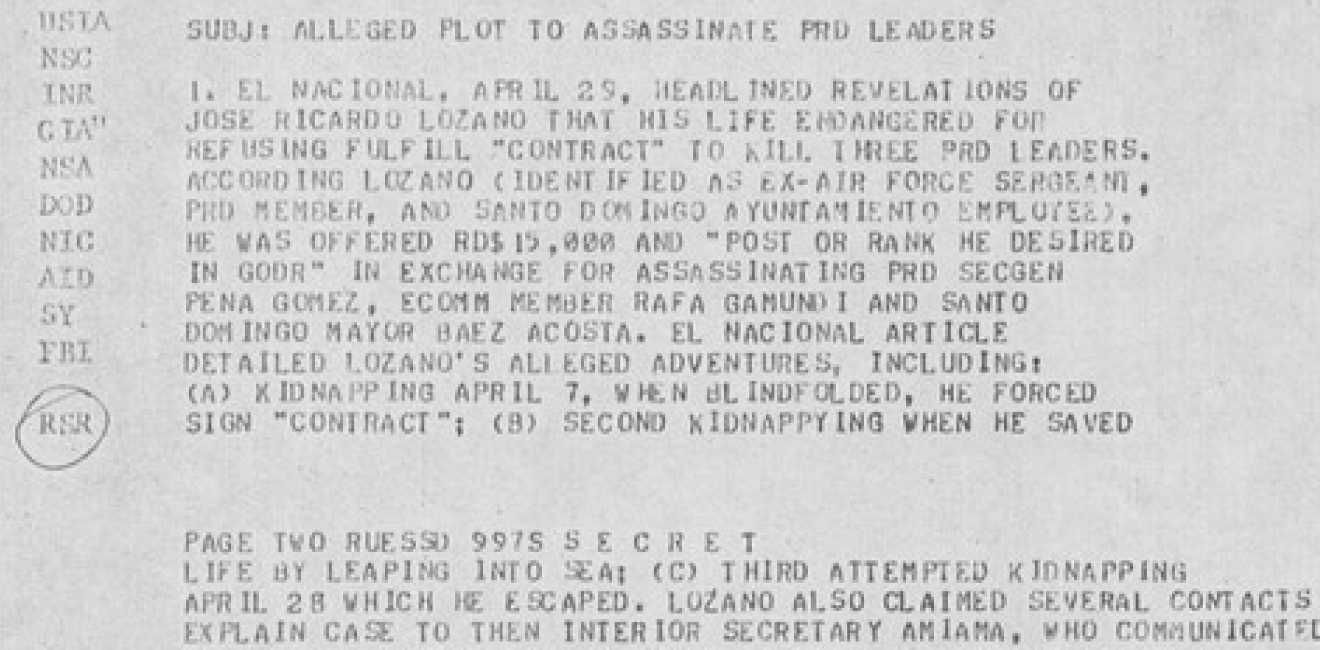

My digitization project, Opening the Archives Dominican Republic Project (OTA), attempts to harness this current shift of the Latin American archive to facilitate accessibility for those shut off from the archive. OTA makes US government documents about the Dominican Republic during the Cold War years of the 1960s and 1970s available and searchable. As coordinator of the project, under the leadership of Professor James N. Green and with the support of a team of researchers, this initiative was designed to encourage Dominicans to have fuller access to information of the history of their country and its relationship to the United States.

OTA presents an opportunity to make archival collections about the Cold War in the Dominican Republic available to children of Dominican immigrants. OTA is based at the Brown University library in Providence, Rhode Island – one of the biggest enclaves of Dominican immigrants, second only to New York. The project is now being pitched to integrate it into secondary school history curriculums. This means that the process of archival redemption is being passed down to second and third generation Dominicans.

We see a similar process in Guatemala, where the sudden reappearance of 75 million police documents is impacting post-Cold War activism. The discovery of these archives, historian Kirsten Weld recounts, renewed the national conversation about historical memory and transnational justice. The internationally funded initiative, the Project for the Recovery of the National Police Historical Archives (PRAHPN), is saving the damaged documents and analyzing their contents with the goal of prosecuting officials for crimes against humanity during the brutal civil war in Guatemala.

In the Guatemala scene, not only is the archive the site of individual redemption but of national reckoning. As Weld puts it, which is both true for my mother and for Guatemala as well as the rest of Latin America, “Documents, archives, and historical knowledge are more than just the building blocks of politics – they are themselves sites of contemporary political struggle.”