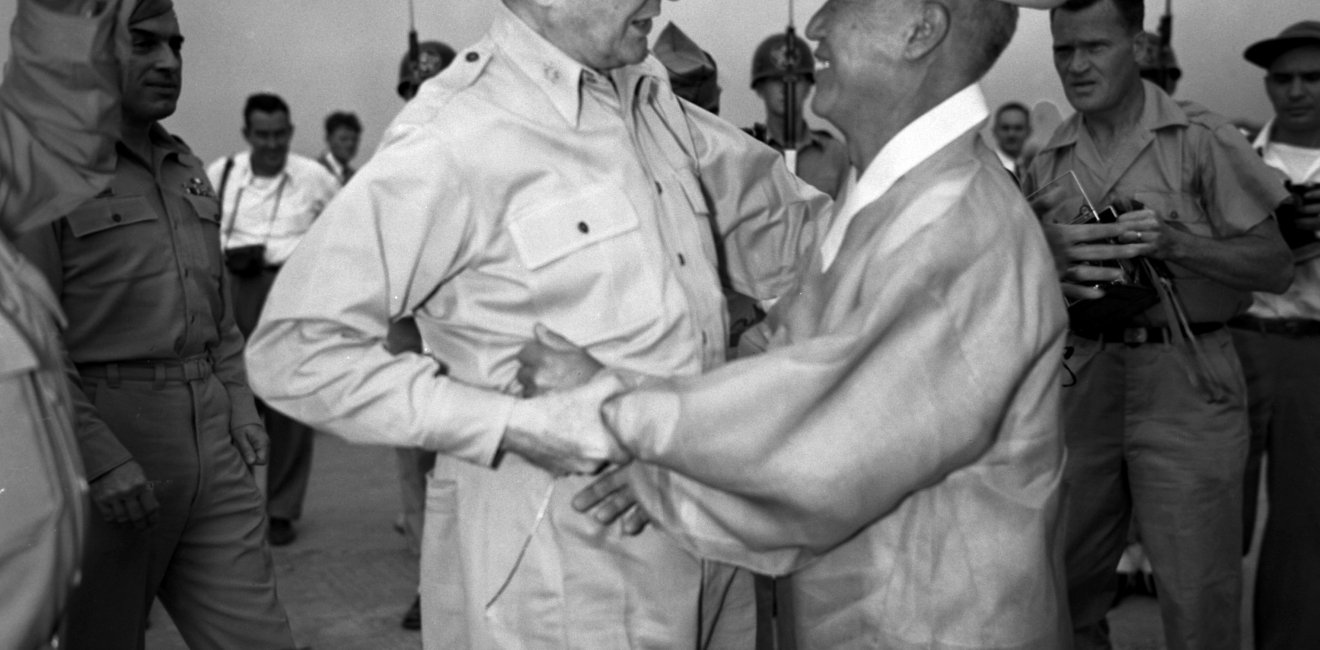

Left, Right, and Rhee

The political views of South Korea's first president betrayed the left-right spectrum. According to David Fields, this means that the Korean War's origins are even more complicated than commonly thought.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

The political views of South Korea's first president betrayed the left-right spectrum. According to David Fields, this means that the Korean War's origins are even more complicated than commonly thought.

The complicated political views of South Korea’s first president reveal the tangled origins of the Korean War

In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen the United States supported during the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945—courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of “righting” a newly liberated Korea that was lurching to the left.

But beneath the weathered façade of one of the Cold War’s more virulent anti-communists was a man whose political views and policies cannot simply be labeled as right-wing. Many of Rhee’s writings and policies reveal a pragmatic, non-ideological man, who could just as easily be placed on the left of the political spectrum as on the right, especially in the realm of economic policy.

More than a few Americans would discover that underneath Rhee’s hard anti-communist shell lay a pink core. American experts examining the first constitution of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1948 commented on how it essentially created a socialist state. A United Nations report compiled pre-Korean War (but published in 1951) on foreign investment in the ROK made grim reading for international capitalists. Nationalizations were rife and the remittance of profits was at the discretion of the finance minister.

The State Department and American businessmen waited in vain for Rhee’s administration to pass legislation creating legal protections for foreign direct investment in the ROK. Such legislation would not be passed until two years after Rhee’s forced resignation. Dismayed US Congressmen tried twice in 1954 to pass legislation that would have prevented aid to Korea from being used to “continue the present socialized status” of the Korean economy.

Knowing that Rhee’s politics cannot be mapped easily on a left-right spectrum is crucial to understanding the tangled origins of the Korean War. For too long, the dominate narrative of the origins of the Korean War has been that the United States foisted a reactionary regime of collaborators on a newly liberated population looking for radical change. The notion that Rhee was “installed” by the United States appears regularly in literature on Korea written by scholars who are not specialists in this period.

Far from being installed by the Americans, Rhee began alienating the American military government in Korea almost as soon as he arrived. He attacked the policy of trusteeship for Korea and demanded nothing less than immediate independence. This infuriated American General John R. Hodge, but endeared him to the majority of Koreans who viewed trusteeship as a continuation of colonialism under a different guise.

Although Rhee had no qualms about accepting money from wealthy and landed Koreans, some of whom were collaborators, he was never beholden to them. Such individuals were key supporters of Rhee during the American occupation, but he refused to include even one of them in his first cabinet and then executed a sweeping land reform over their objections and the objections of their party, the Korea Democratic Party.

Rhee’s land reform, which began in 1950, but was not completed for many years because of the Korean War, is probably the most important legacy of his administration, and also the one that is least remembered. In 1945, two-thirds of arable land in Korea was owned by just 3 percent of the population and 80 percent of rural Koreans owned no land at all. By 1957, war and land reform had nearly reversed that statistic: 88 percent of rural Koreans owned land.

By providing rural Koreans with a modicum of social security, Rhee earned a broad base of support that no external power could have given him. Land reform was Rhee’s proof that he was not a reactionary, even as he carried out a campaign of extermination against communists.

My purpose in arguing that Rhee’s political ideas were left-of-center is not to rehabilitate him or absolve the United States of responsibility for its many mistakes in Korea. It is important to be critical, but to be critical for the right reasons. Rhee was a deeply flawed leader for many reasons; being a reactionary was not one of them.

Likewise, American policy in Korea lurched from disaster to catastrophe, but not because it was committed to imposing a right-wing, capitalist ideology on Korea. Most of the mistakes of the American military government in Korea—starting from initial announcement that Japanese colonial officials would be retained—spawned from the hasty decision to embark on a major occupation without much of a plan.

Unware of why they were in Korea in the first place, American policymakers were eager to leave, and reluctant to give any assurances to the Koreans that they would return, even in the event of communist aggression. Rhee spent his first two years as president begging for reassurance that the United States would defend the ROK from external aggression. Had he received it, the whole history of the Cold War might be different. Stalin was only willing to approve Kim Il Sung’s invasion once he was convinced that the United States did not intend to intervene.

These and many other flaws become apparent when we acknowledge the limits of imposing a left-right paradigm on post-liberation Korea. As those on the ground in the CIA and the State Department observed, and as historians such as Allan Millett have argued, virtually all Koreans in post-liberation period where leftist. They all supported sweeping land reform, the nationalization of industries, a large centralized state, and a robust social safety net. While Korean society was certainly leaning to the left, it was also deeply divided. Setting aside the left-right paradigm allows other, more fundamental, divisions to come into relief.

The more scholars acknowledge the shortcomings of the left-right paradigm in Korea and find their own paths through the various archives of post-liberation Korea and the Korean War, the richer our understanding will become. An under-utilized resource for this period are the Papers of Syngman Rhee housed at Yonsei University, in Seoul, South Korea. Despite being over 100,000 pages and mostly in English, this collection has seen shockingly little use. It was while working in this collection and editing Rhee’s diary that I became aware of Rhee’s left-of-center associates, policies, and writings. Surely many more discoveries await researchers there.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

The North Korea International Documentation Project serves as an informational clearinghouse on North Korea for the scholarly and policymaking communities, disseminating documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that provide valuable insight into the actions and nature of the North Korean state. Read more