A Lesson from the 1981 Raid on Osirak

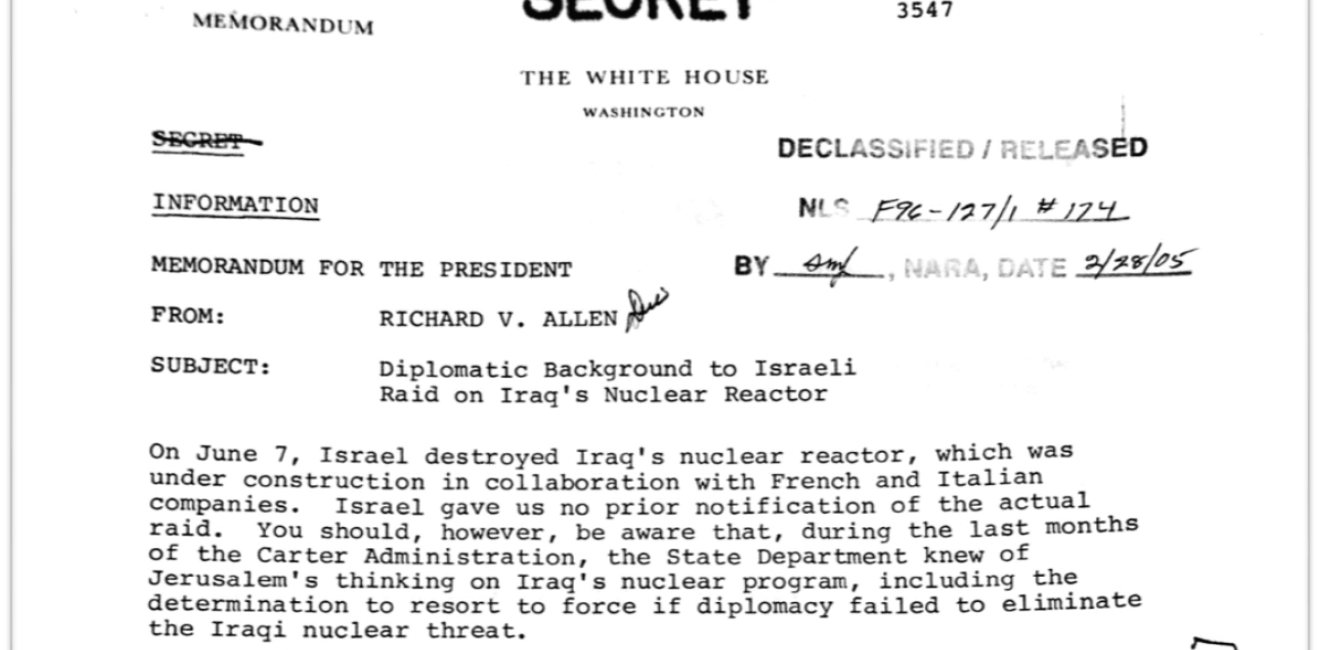

A breakdown of communication between Reagan's White House and the intelligence agencies allowed an Israeli strike on Iraq's Osirak reactor to catch the administration completely off-guard.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

A breakdown of communication between Reagan's White House and the intelligence agencies allowed an Israeli strike on Iraq's Osirak reactor to catch the administration completely off-guard.

On the evening of Saturday, June 7, 1981, US Ambassador to Israel Samuel Lewis received an unexpected phone call from Menachem Begin, the Israeli Prime Minister.

The ambassador’s staff had traced Lewis to the Hilton Hotel, where he was prepping William Butcher, the chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank, for a Ministry of Finance dinner later that night. He accepted the call while perched on the edge of a bed in Butcher’s suite, unprepared for the short, stunning message that Begin delivered. Lewis explained what had occurred in a flash cable to Washington:

At 1940 local (1740 ZULU) Prime Minster Begin contacted me and asked me to convey the following message to you as quickly as possible. Commence text. Today our air force carried out a raid on the atomic reactor near Baghdad. According to the reports of our pilots the target was completely destroyed. All our planes returned safely. End text.

Additional details of Operation Opera slowly trickled in. Fourteen American-built F-16 fighter aircraft had taken off from an Israeli airstrip in the Negev, cutting through Jordanian and Saudi airspace as they raced towards Iraq. With no possibility of an emergency landing, the pilots flew low and evaded detection by US Airborne Early-Warning and Control Systems (AWACS) temporarily stationed in Saudi Arabia.

In less than an hour, they reached their target: Iraq’s Tamuz 1 reactor site, located 10 kilometers southwest of Baghdad. While Israeli ministers tracked the operation from Begin’s home in Jerusalem, eight of the pilots dropped a dozen or so 2000-pound bombs upon the cement reactor shell below. In under two minutes, Iraq’s fledgling nuclear program was destroyed.

In 1991, then Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney praised the “outstanding” Israeli operation for “ma[king] our job much easier in Desert Storm.” Ten years earlier, however, American officials had a much different take on Operation Opera.

Embassy staff in the region warned of Arab retaliation. The raid, one official confided to the press, had evoked “institutional memories of what happened in 1967,” when an Israeli attack on Egypt’s air force sparked a major regional conflict and led several states to sever relations with the United States. Some US officials, unsure if the Tamuz reactor had gone ‘hot,’ also scrambled to determine whether radioactive material was leaking from the damaged facility.

In his diary, even President Ronald Reagan voiced extreme pessimism: “I swear I believe Armageddon is near.”

The risk of escalation faded quickly, but the raid’s consequences for the United States did not. The strike occurred three days after an Israeli-Egyptian summit, forcing an increasingly isolated Anwar Sadat, then President of Egypt, to defend himself against accusations of collusion. Similarly, the operation derailed negotiations in Lebanon, where an Arab Conciliation Council was working on the United States’ behalf to de-escalate a dangerous Israeli-Syrian standoff in the Beqaa.

The “chorus of invective,” in one ambassador’s words, quickly focused on the United States’ presumed complicity with the Israeli operation. The effects were wide-ranging. As a July intelligence assessment summarized:

On balance, this attack has hurt US interests. It has complicated the search for a coherent strategic approach in the Persian Gulf area, strengthened the hand of the more radical Arabs, provided more grist for Soviet propagandist, and driven a potential wedge between the United States and its moderate Arab partners.

The Reagan administration was put on the defensive. In an effort to assuage Arab anger, it suspended the delivery of six F-16 aircraft to Israel and voted in support of a UN Security Council resolution condemning the raid, infuriating Israeli officials who insisted that they had acted in self-defense. The administration doubled down on a controversial arms package to Saudi Arabia in the early fall, provoking a bruising congressional battle that deepened the gulf between Washington and Jerusalem.

As a result, the Reagan administration’s influence over Israel’s foreign policies weakened just as Prime Minister Begin embarked on a series of dramatic military operations, including the bombing of PLO headquarters in Beirut in July 1981, the annexation of the Golan Heights in December 1981, and the sudden invasion of Lebanon in June 1982—all of which heightened tensions and weakened the United States’ position in the region.

The June 7 attack on the Tamuz 1 reactor and the subsequent chain of events were not inevitable. The archival record suggests that the Reagan administration should have had sufficient information at its disposal to predict—and perhaps prevent—the Israeli raid. Indeed, as Lewis delicately explained in a cable to Secretary Haig on June 9, Israeli officials had indicated their intention to strike the Israeli reactor multiple times during nearly a year of high-level negotiations with the Carter administration. These talks, the ambassador wrote, “left me with no doubt that before the Iraqi reactor became operational, the Israeli forces would destroy it.”

Lewis highlighted three specific incidents in the year before the attack, and even provided the cable numbers of relevant embassy cables for verification. On July 17, 1980, Begin had summoned Lewis to his home. The Israeli Prime Minister requested that the ambassador transmit an “emotional personal message” appealing to the Carter administration to “do everything possible to stop further enriched uranium shipments to Iraq before it was ‘too late.’” Alarmed, Lewis ended his message to Washington with a prescient warning:

We must anticipate that [Israel] will feel compelled in the not too distant future to take some kind of unilateral action to thwart the Iraq nuclear plans well before the Iraqis actually possess a weapon. And by the ‘very near future,’ I mean within the next six months.

Additional evidence of an impending Israeli operation piled up throughout the fall of 1980, prompting Lewis to warn of “a number of thinly veiled straws” in the wind. In mid-December—three weeks after Reagan’s election—the ambassador received authorization from Secretary of State Thomas Pickering to meet with Begin to stress the need for restraint. The meeting was unsuccessful, and in a summary report to Washington Lewis noted that the Israeli military command was “press[ing] Begin hard” to take military action. “To maintain any kind of influence over the very dangerous possibility for direct Israeli military preventive moves,” he wrote, “it is vital that we continue to carry on a frank dialogue with Begin or his successor. At some point, the new administration should be carefully briefed.”

Lewis’ warning fell on deaf ears. Although he personally contacted the transition team to draw attention to the dangers, his reports were either lost or dismissed by the incoming Reagan administration. Moreover, the president’s selection of Alexander M. Haig, Jr., as Secretary of State isolated many career civil servants and Foreign Service Officers, who eyed the unusually ideological White House and ex-Nixon official with suspicion. The channels of communication linking embassy staff to Foggy Bottom narrowed, limiting the opportunities for senior policymakers to learn of the problem. As a result, consultations with the Israelis lagged. Begin, who felt in the winter of 1981 that he enjoyed the new administration’s natural sympathies, likely viewed Washington’s silence as implied consent.

Had Lewis’ warnings been heeded, the Reagan administration may still have been unable (or unwilling) to dissuade Israeli policymakers from bombing the Iraqi nuclear facility. Yet knowledge of the Carter administration’s negotiations and the warning signs would have—at minimum—allowed US policymakers to influence the timing and nature of the Israeli operation and limit the political fallout for the United States.

Instead, as Lewis noted pessimistically, the Israeli selection ensured the “strike occurred at a moment when it could scarcely have been more damaging.”

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more