New Sources for the Study of Cold War India

"Ideas of India" is a newly launched database that makes a broad swathe of historical Indian periodicals accessible, sources that show the roots of Indian diplomacy during the Cold War.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

"Ideas of India" is a newly launched database that makes a broad swathe of historical Indian periodicals accessible, sources that show the roots of Indian diplomacy during the Cold War.

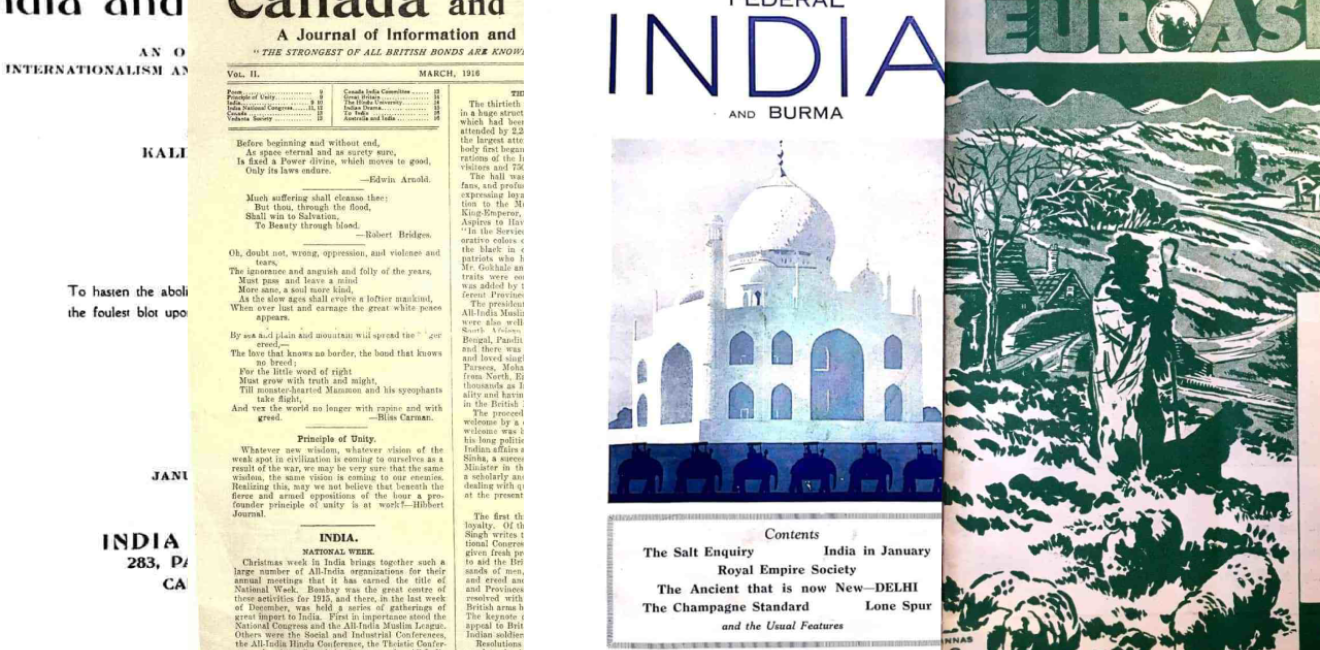

Ideas of India is a newly launched database that makes a broad swathe of historical Indian periodicals accessible. The site currently houses 255 periodicals with 315,000 entries. After March 2020, the site will be updated to include 365 periodicals with some 350,000 entries. The database indicates that the periodicals were published between 1837 and 1947, although some continued even after India acquired independence in 1947. Most of these periodicals are now defunct, but the archive thrives.

The database supplements other online repositories, such as the National Digital Library of India and archive.org, that have digitized the content of Indian periodicals – albeit with terribly inadequate metadata. Ideas of India is impressively indexed and organized; it offers unprecedented access to the vast world of periodicals in India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Rahul Sagar, a Global Network Associate Professor of Political Science at NYU Abu Dhabi and the creator of the database, estimates that when they were in circulation, the average readership for the periodicals was about 600 official readers, which could have meant upwards of 3,000 readers due to the practice of sharing.

These periodicals grew out of the yearning of Indians who had received an English language education to have fora for political and social debate and discourse. They were founded in and around cities that had universities, including Calcutta, Madras, Allahabad, and Bombay, and then later expanded to Lahore, Patna, and Delhi. They received patronage from Indian princely states, particularly from the rulers of Baroda, Mysore, and Travancore, who had themselves benefitted from high levels of education, saving the publications from penury and a threat to their very survival at times of extreme hardship such as during the Great War.

Even though public debating predated colonial rule in India, the British had roused that culture further by imposing English-language education on Indians who were thus far conducting most public discourse in the vernacular. More directly, English intellectual life provided a model for this newly emerging culture to be written and read. Most periodicals were fashioned on an English equivalent. As with the language itself, English periodicals in India came to be seen as a source of modernity, a space for writers to bring their views into sharper focus through interface with an equally highly educated audience. British rulers, by reading such periodicals and describing their contents as valuable sources of opinion in the colony, provided a sense of authority to the publications and validated the debates taking place there within.

The publications with the most visibility - The Calcutta Review, The Modern Review, The Hindustan Review, The Indian Review - enjoyed readership across India, in England and in other colonies in Fiji, the Caribbean, Burma, Sri Lanka, and the Far East. Indeed, as even a cursory glance through the index shows, India had a vast network of transnational relations well before the British had left and India had become a member of the United Nations.

The roots of later Indian diplomacy are to be found in these periodicals; it is these publications that shaped the thinking of modern India about the world around it. Editorials on India’s relations with the world are equal in number to opinion pieces on world political events that have very little direct consequence for the Indian nation or on Indian society. There is a focus on the diaspora too – and not just the Indian diaspora. One of the most interesting entries in the database is The Iran League Quarterly, which is about the Iranian community in India that settled in Bombay.

There is also a remarkable parlaying of views, with an argument being presented in one issue of a journal and being responded to in the next, or indeed, in another journal. In that sense, the periodicals, read collectively, illustrate a level of selfhood taking shape across many national formations within the loose bounds of India and coming together then in 1947 in the form of a clearly marked republic.

This sort of diffuse political debate also gives us a chance to go beyond the biographical focus on personalities, whose politics has proven to be so polarizing in the present day. Indeed, the whole question of what constitutes an archive is germane when competing accounts of history are in circulation.

Letters, memoirs, biographies and government documents have been of immense value to the writing of Indian international history, but they have been lacking in one aspect – they do not offer a plurality of views in the form of a debate. So, the historian runs into the issue of embedding a text with too little or too much meaning. The earliest corrective to this gap can be seen in studies using Indian parliamentary debates, where all political inclinations are necessarily party to the same conversation, and often articulate their arguments in a dialectical form. The precursors to that dialoguing can be found in the pages of the periodicals in Ideas of India.

Finally, the archive points to its own legacy in one way above others – in operating within the confines of colonial censorship, the periodicals often relied on dispassionate argumentation. While the Indian freedom movement was underway, peopled by forceful orators, the flourishing of Indian periodicals was still very much policed by the colonial administration. There emerged, thus, a dichotomy: the use of rhetoric as a performative act by political actors, rather than by political commentators – a crucial segregation that allowed the elevation of public discourse in parallel to but not separate from an increasingly animated politics, both with their own uses. The ideas expressed in the periodicals were often distilled and amplified in political speech, but the coherence of the argument can be analysed in its written form. This makes Ideas of India a vital historical source to understanding India’s views on a world marked by imperial rule and Cold War politics.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more