North Korea, the Smuggler State

In the fall of 1976, North Korean diplomats were expelled from Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden for smuggling alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

In the fall of 1976, North Korean diplomats were expelled from Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden for smuggling alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.

If the international community really wants to halt the North Korean nuclear program, it may need to catch more than a few boats.

The United Nations Security Council passed its strongest sanctions yet against North Korea on September 11, 2017. Resolution 2375, a response to North Korea’s 6th and most powerful nuclear test, will shrink the country’s exports, reduce its overseas worker programs, and curtail how much petroleum it can import if properly enforced.

None of this bodes well for the North Korean economy, but there’s yet another piece to the UN resolution that could sting Pyongyang. The new sanctions also give greater power to states to stop and inspect ships suspected of smuggling banned items—such as arms, textiles, and coal—from the DPRK.

In the past, lax enforcement from China, Russia, and other key “investors” in North Korea has softened the actual impact of UN sanctions. But Pyongyang’s resilience, as this resolution acknowledges, is also in large measure due to its diverse criminal economic activities.

According to the research of Sheena Greitens and other experts, North Korea has relied on smuggling and other illicit activities to help shore up its moribund economy since at least the 1970s. Pyongyang has furnished drugs, alcohol, tobacco, weapons, and other unsavory items to criminal gangs, warlords, illegitimate regimes, and even affluent buyers in the developed world.

The first well-known case of North Korean smuggling occurred in the fall of 1976, not long after the DPRK established diplomatic relations with Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Norway.

The opening of four embassies in Scandinavia was a coup for North Korea at the time, giving the regime greater diplomatic legitimacy and, it hoped, new trade partners and investors for its already struggling economy. But in an embarrassing turn of events, the governments in Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Norway all announced in quick succession that they had uncovered evidence of accredited North Korean diplomats smuggling alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.

Until recently, files on North Korea’s botched smuggling operations were inaccessible in Scandinavian archives—an unusual state of affairs given how much time has elapsed and these countries’ track records for transparency. But the details are now coming to light following successful declassification petitions that I made on behalf of the North Korea International Documentation Project (NKIDP) to the ministries of foreign affairs in Oslo and Helsinki. (Similar requests to the authorities in Denmark and Sweden are still pending as of writing.)

1,000 bottles of beer on the wall…

News of the smuggling scandal broke in October 1976 after more than a month of police investigations in all four countries.

On October 18, police in Oslo submitted evidence of crimes committed by the DPRK mission to the Norwegian Foreign Ministry. The North Koreans were certainly carrying out a “large-scale” operation to smuggle alcohol and cigarettes into Oslo, the police wrote, while criminal confessions from Norwegians strongly suggested that the North Koreans were also trafficking drugs into the country. The police identified North Korea’s non-resident ambassador, Gil Jae-gyeong (then stationed in Sweden), as well as the Charge d’Affaires in Oslo, Pak Gi-pil, as leaders of the smuggling ring and suggested all North Korean embassy staff in Norway immediately be declared “persona non grata.”

A subsequent Norwegian police statement called the illegal activities of the North Koreans “extensive”—over 4,000 bottles of liquor and 7,000 packs of cigarettes were smuggled into Norway using diplomatic pouches and then sold on the black-market. Police in Finland tallied a sale of over 3,000 bottles of liquor and over 2,500 bottles of beer.

The Norwegian Foreign Ministry acted quickly following receipt of the police report. It issued a press release that same day announcing that North Korean embassy staff were “unwanted” and had less than one week to depart the country. Days later, Finland also announced that North Korean diplomats had “violated regulations related to alcoholic beverages” and were being asked to leave the country immediately.

Several of the newly declassified files suggest that all of the affected countries shared information about North Korea’s smuggling operations in September and October and coordinated their responses.

Further investigations by Norwegian intelligence concluded that the operation in Scandinavia was part of a larger criminal network run by DPRK embassies in the Eastern bloc. Finnish authorities pointed to Poland as the “center of the illicit trade.” Newspapers in West Germany claimed DPRK agents in East Berlin, including the North Korean military attaché, coordinated the smuggling in Northern Europe, in addition to engaging in arms sales and other criminal activities.

Upon reading West German allegations that East Berlin was the “headquarters” of North Korea’s “smuggling organization….and intelligence activities,” GDR officials pledged to thoroughly investigate the matter without commenting on the validity of the claims. In contrast, Soviet personnel made no effort to dispute the allegations. In one candid talk, an unnamed Soviet official admitted to the Norwegian Ambassador in Moscow that the North Koreans engaged in illicit activities even in the USSR. “Some North Koreans had left Moscow,” the official reported, “as a result of their involvement in drug smuggling.”

Weathering the storm

Why was North Korea willing to contravene the laws of Scandinavian countries, and even a close socialist ally? Kim Il Sung, North Korea’s founding leader, had a “Napoleon complex,” the Soviet interlocutor remarked.

The US intelligence community offered less colorful explanations: with limited operational funding provided by Pyongyang, the embassies often had to fend for themselves. “The illegal actions in Scandinavia,” read one daily report, “were part of a systematic effort by the North Koreans to exploit their diplomatic status for profit.”

Norwegian police concurred with this analysis. Pyongyang had set “revenue targets” for the embassies in Scandinavia, in part to fund the missions and, probably to a lesser extent, to generate remittances for the Korean Workers’ Party.

Unsurprisingly, North Korea flatly denied the allegations from Finnish and Norwegian police, as well as those coming from Denmark and Sweden. Shortly after news of the smuggling operation broke, North Korea’s ambassador in Beijing, Hyeon Jun-geuk (Hyun Jun Guk), called on Torleiv Anda, Norway’s non-resident ambassador to Pyongyang, to “[express] doubts about the validity” of the Norwegian police investigation.

The DPRK Ambassador could “hardly believe that members of North Korea’s Embassy had been engaged in illegal activities.” If any smuggling had in fact taken place, Hyeon explained, then it was “individuals acting against the will of the North Korean government.” He again denied the conspiracy several days later during a follow-up meeting with Anda.

In Helsinki, the North Korean chargé similarly proclaimed that the allegations were baseless. “We do not admit anything,” he said.

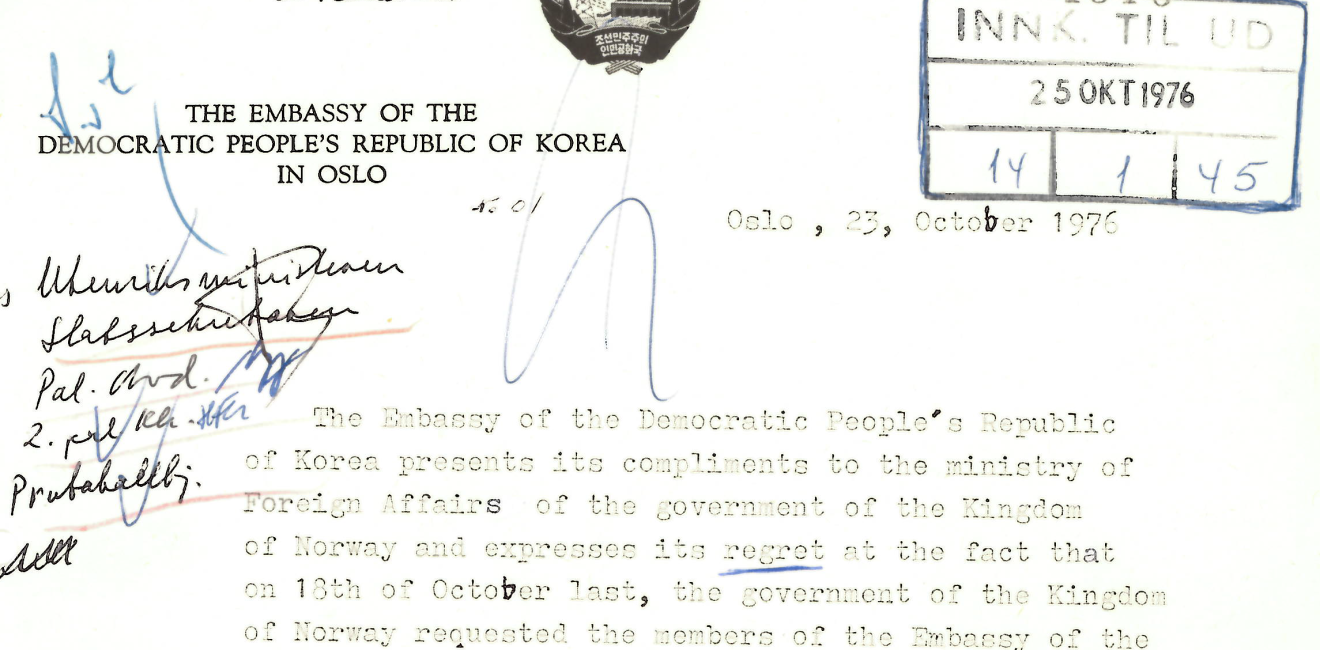

On October 23, the DPRK mission in Oslo formally repudiated the allegations in a statement. The embassy called the expulsion of its diplomats “unexpected,” a blow to the “friendly relation [sic]” between Norway and the DPRK, and entirely “unjustified.”

Norway’s Foreign Ministry did not waver. In a response to the October 23 statement, the Ministry insisted that the evidence of criminal activity was “incontrovertible” and the decision to expel the diplomats “fully justified.” As a result, “the Norwegian Government cannot bear any responsibility for possible negative effects on the relations between our two countries.” Rather than continue to protest, the North Koreans were encouraged to replace the staff declared persona non grata.

In Finland, North Korean officials not only complained about the expulsions, but also about the bad press that the smuggling incident generated. When prompted by a DPRK official to take action, Finland’s Secretary of State dismissively remarked that “it is not possible for the Foreign Ministry to prevent such writing” about North Korea in local newspapers.

Yet, bad press aside, North Korea largely weathered the storm. The government of Finland, stressing that it was “crucial to maintain a good continuing relationship” with North Korea, opted not to shutter Pyongyang’s mission entirely. The Finnish Government also stopped short of directly labeling the North Korean diplomats as “smugglers.” Authorities in Helsinki instead emphasized that the North Korean Embassy had violated the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations because it did not pay customs taxes on the alcohol brought into Finland.

By 1978, the North Korean embassies in Scandinavia appear to have resumed operations at full staffing levels, with ambassadors present.

The smuggler state, then and now

North Korea’s ability to overcome this scandal in Scandinavia can, of course, be credited to a political environment particular to the Cold War. Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland— eager to transcend East-West barriers and stake out a middle ground between Cold War camps—controlled their outrage at North Korea’s illegal activities and allowed the country to retain its embassies.

Scandinavian acquiescence to North Korean misbehavior may have encouraged the DPRK to continue its smuggling operations abroad. Ample evidence shows that, all the way to the present, North Korea has continued to use its embassies to raise hard currency, through both legal and illegal channels. Only recently, with the passage of UN Resolution 2321 following North Korea’s fifth nuclear test, has the international community taken a stronger stand against these money-making operations. And now with Resolution 2375, North Korea’s broader smuggling capabilities are coming under greater scrutiny.

These are promising developments, but it is worth bearing in mind that North Korea is a nuclear-armed state that abhors international norms (it even ignored socialist norms during the Cold War) and is relentlessly seeking to perfect its missile delivery systems. The novice behavior of North Korea's diplomats in 1976 bears little resemblance to the expert criminality of the country today. No doubt, if it is helpful to Kim Jong Un’s nuclear ambitions, the DPRK will continue to smuggle and will find new ways to do so.

If the international community really wants to halt the North Korean nuclear program, it may need to catch more than a few boats.

Special thanks to August Myrseth and Ulla-Stina Henttonen for assisting in the translation of, respectively, the Norwegian and Finnish files--all of which are now freely accessible on DigitalArchive.org.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The North Korea International Documentation Project serves as an informational clearinghouse on North Korea for the scholarly and policymaking communities, disseminating documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that provide valuable insight into the actions and nature of the North Korean state. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more