Researching the Global Cold War in South Africa’s Archives

Archives in Pretoria and Bloemfontein offer opportunities for researchers of nuclear and Cold War history.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Archives in Pretoria and Bloemfontein offer opportunities for researchers of nuclear and Cold War history.

Archives in Pretoria and Bloemfontein offer opportunities for researchers of nuclear and Cold War history.

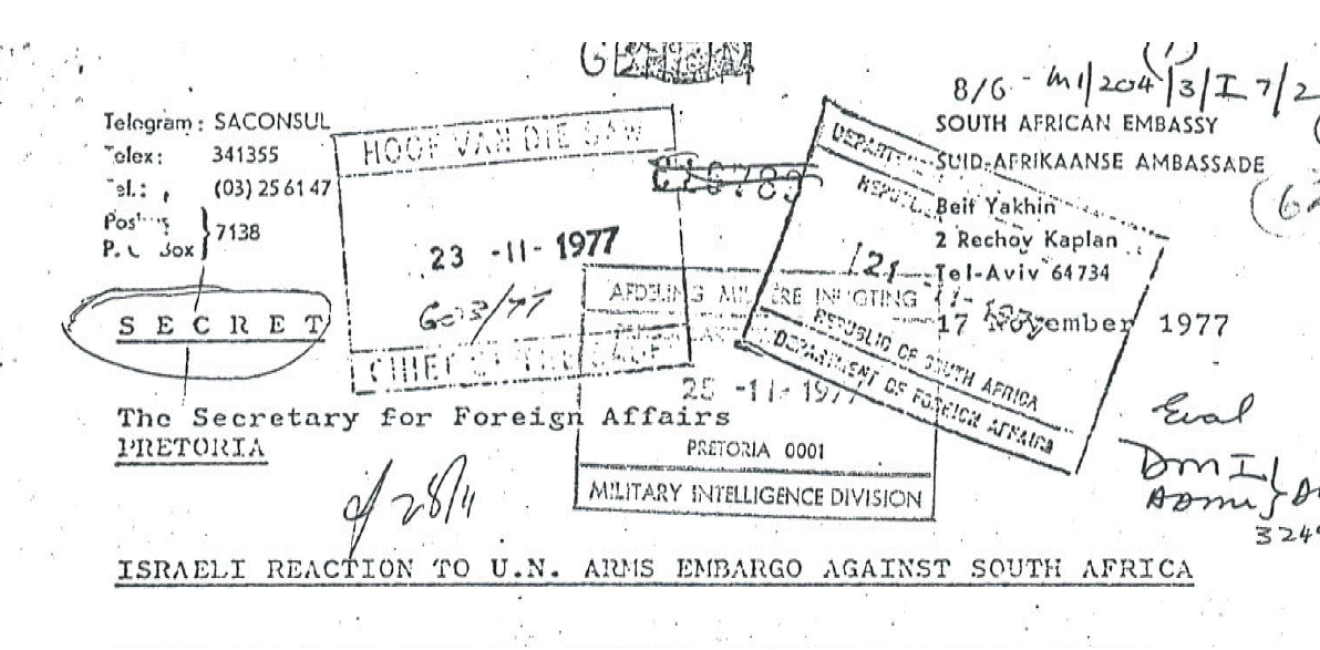

South Africa is the only state to develop and later renounce nuclear weapons. Yet many questions about the scope of the program and the decisions that lead to its termination between 1989-90 remain. As access to archives and primary sources expands, the South African case deserves renewed attention.

Between 2016 and 2017, I spent nine weeks researching the end of the South African nuclear weapons program, first independently and later as a NPIHP fellow and guest of Monash South Africa. In this post, I share some observations and recommendations for researchers seeking South African archival records on the global Cold War.

Before embarking for Pretoria, I found two resources to be very helpful in planning my trip to the archives: Sue Onslow’s research report on the state of South African archives and the background information on the ArchivesMadeEasy website, compiled by Jamie Miller. These two sources are, respectively, six and twelve years old, so I will present some of the new procedural changes below. In addition, I recommend that researchers understand the system for classification in South Africa and the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA)—South Africa’s analogue to the US Freedom of Information Act. The South African Historical Archive (SAHA) website hosts excellent background documentation on this process.

The entrance to the DIRCO Archive, formerly the Department of Foreign Affairs Archive (DFA), is located in the underground car-park beneath the OR Tambo Building in Pretoria. Most important of all: this archive is no longer easily accessible for the public and it is impossible to access the reading room without prior invitation. In addition, the archive has no public website.

To start the process, I recommend contacting the archivist, Ms. Ronel Jansen van Vuuren, with a detailed request indicating what materials you seek. The staff will write back once they complete their procedure—in my case this took three months. If the archivists discover records responsive to your search, you are obliged to pay ZAR 35 (USD 2.63) per PAIA request. They will subsequently grant either access to the reading room or send you the scanned documents via email. In general, email conversation is quick and reliable.

The finding aids are available only in paper form and are organized by country. Visiting researchers rarely have the opportunity to consult them directly—search requests are relayed through the staff, who are friendly and do their best to locate records responsive to the request. This procedure is new, following the retirement of the former head of the archive in mid-2016.

It was not clear how far back in time the DIRCO records reach. Some documents I requested were in transit to the National Archives and could not be accessed.

The Archive of Contemporary affairs holds the papers and records of politicians and diplomats from the Apartheid era, excluding “Pik” Botha, who is believed to hold papers relating to his time as foreign minister (1977–94) in a private collection at his home (currently inaccessible due to his reluctance to host researchers, due to his advanced age).

I mostly engaged with the inventory of the Political Collection at the Archives of Contemporary Affairs and particularly with the papers of former cabinet members and ministers under presidents PW Botha and FW de Klerk. Additionally, I read reports and summaries that had been send to President PW Botha by the head of the Atomic Energy Corporation pertaining to negotiations at the IAEA about South African NPT accession in the mid-1980s.

The archives at Bloemfontein have an electronic finding aid and I was able to order documents prior to my arrival. I was the only researcher working on one of the voluminous wooden desks—there is plenty of space to spread out the documents and delve into them. The archive is located on the campus of the University of the Free State, and a typical South African food court is within walking distance.

The archive staff is supportive and even provided coffee and tea twice a day. Around 10:30am every morning, the three staff members meet for their daily chat over tea while being immersed in knitting. This contributed to the almost family-like atmosphere.

As elsewhere, South Africa’s archives are understaffed. This translates into a processing backlog for the many requests made by scholars from all over the world. On the other hand, the staff of the two archives I consulted were helpful, supportive, and knowledgeable about their holdings.

When I arrived, I was concerned that relying on the archivists to search for my documents would be a barrier—I feared that they would have insufficient background in my subject area to locate relevant records. However, the DIRCO archivists cooperated with staff from other departments to locate files responsive to my requests.

Preserving archival records—especially those from the Cold War era—is not a priority of the current government. In my view, this results from an unfavourable combination of lack of funds and a general indifference regarding records that date back to the Apartheid era. Nevertheless, once you are in the archives and talk to the staff personally, one can much better explain what it is you are looking for.

Language represents a final barrier to using South African records to research the global Cold War. Most government records and personal papers are written in Afrikaans and only partially in English. Dutch-speaking researchers should not encounter major problems, and researchers able to read German should be able to judge if a particular document is relevant to their research. The holdings of the DIRCO Archive, however, are mostly in English, due to its diplomatic nature.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more