Robert Williams in China: Contesting Race, Class, and Black Nationalism

Ruodi Duan recounts the arrival of civil rights activist Robert F. Williams's trip to China and meeting with Chinese Communist Party officials.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Ruodi Duan recounts the arrival of civil rights activist Robert F. Williams's trip to China and meeting with Chinese Communist Party officials.

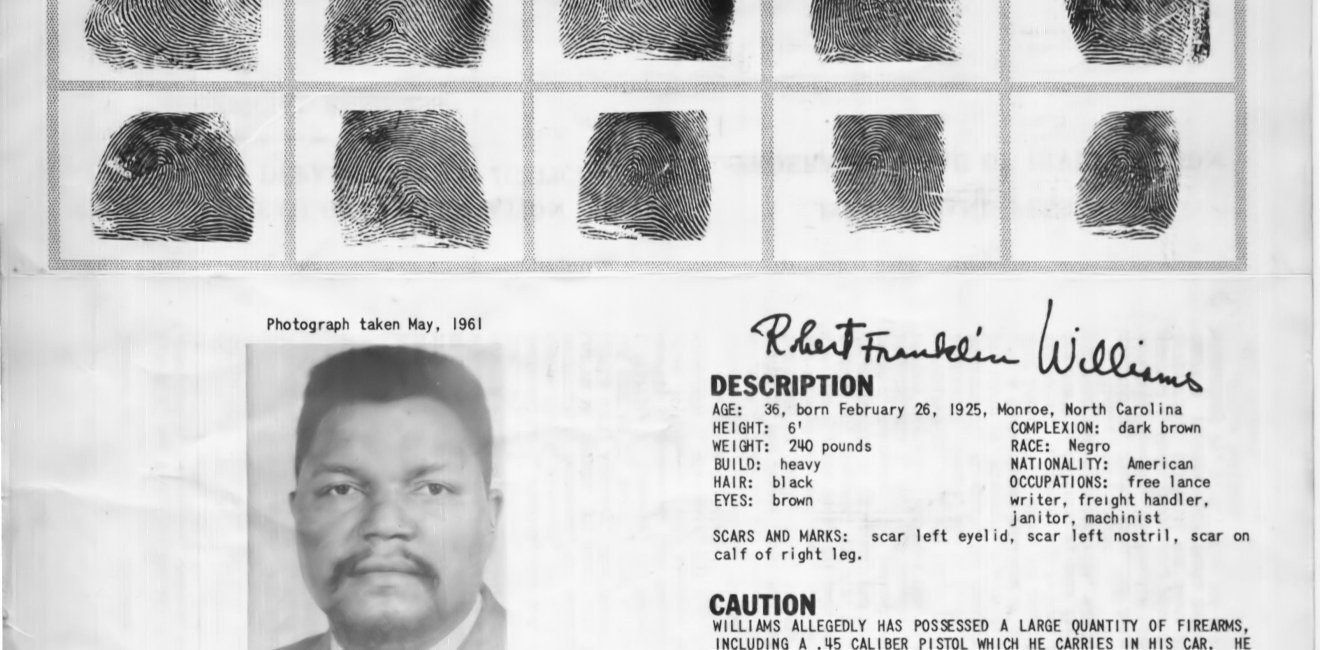

Robert F. Williams, a civil rights activist from North Carolina and advocate of armed self-defense, departed for his first visit to the People’s Republic of China in October 1963 from Havana, where he and his family had lived in exile since 1961. On the eve of Williams’s arrival in Shanghai, a municipal committee charged with his reception gathered to discuss the political objectives of the task ahead. An official in Beijing had passed on the observation about Williams that “[he] doesn’t understand us, and while abroad, has also heard a variety of false Western claims about us… Our conclusion is that we must help him on two fronts. We must emphasize that racial struggle is class struggle and that racial nationalism cannot counter racial nationalism.”[1]

Williams, a black nationalist whose revolutionary politics were anchored in race rather than class, had apparently boasted in Beijing that he convinced the Voice of the Nation of Islam to carry the full text of Mao’s August 1963 “Statement in Support of the Afro-American Struggle” and that his views were increasingly aligned with those of the Nation of Islam (NOI). Disapprovingly, Chinese officials noted that “in discussions…Williams has expressed great interest in [NOI], arguing that they can overturn white supremacist rule [and thereby achieve] black liberation.” [2]

Williams’s insistence that black nationalism alone, especially the separatism that NOI advocated, was the most effective vehicle for African American liberation alarmed his Chinese hosts, who also noted that he had given the cold shoulder to all the white communists from the United States then living in China.

A close reading into the enduring conflicts—as well as the moments of solidarity—between Robert Williams and the Chinese leadership suggests that definitional clashes about race, class, and minority nationalisms posed a major challenge to the Cold War relationship between African American radicalism and Maoism. It also demonstrates that this iteration of Afro-Asian unity was articulated in competition with other formations of anti-imperialist solidarity, especially those centered in Havana and Moscow.

A certain paradox defined Chinese engagements of African American radicalism in the 1960s: while black nationalists like Williams were drawn to China because they viewed its social and economic achievements through the lens of racial nationalism, the Chinese leadership courted African American activists as the vanguard of a broad-based, class-oriented revolution in the United States.

After the Chinese detonation of an atomic bomb in October 1964, Williams celebrated the occasion as a victory for African Americans on the basis of racial confraternity. As he wrote in his newsletter The Crusader, “China’s dehumanization of the past, like the Negro’s today, was based on a system of exploitation master-minded by the same racist savages… [China’s bomb] is also the Afro-American’s bomb, because the Chinese people are blood brothers to the Afro-American and all those who fight against racism and imperialism.”[3]

Here Williams engaged liberally in a politics of analogy that paralleled the Chinese past with the African American present, a line of reasoning often expressed by the Chinese leadership. But taking a different tack, Williams underscored racial co-identification as the basis of African American support for the achievements of Chinese socialism.

Chinese records of Williams’ return visit in October 1964 indicate that camaraderie between the two camps was reinforced with facetious reminders that they shared common political foes. Given the pretext of the Bay of Pigs Incident, Williams joked to Chinese officials that he wanted to ask the Cubans, “Where is your Khrushchev now?” A few days later, when Khrushchev’s resignation came up in discussion, Williams remarked that perhaps, he had stepped down not due to “health reasons” as the Soviet media claimed, but rather, “ill political health.”

Williams also laid out the discontents of his relationship with Fidel Castro. He revealed that before his departure from Havana, Castro personally requested information from him about his visit to China. In response, to the chagrin of Cuban officials, Williams had denounced Soviet “false sympathies” for the experiences of African Americans and praised Chinese socialism. Ultimately, he concluded, though Cuba supported him in his personal endeavours, its “internal revisionism” prevented an endorsement of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), the underground African American nationalist organization that had elected him president. Castro, it turned out, ignored Williams’ ask of $24,000 each year to fund the guerrilla activities of the RAM.[4]

Thus, in spite of his convictions in black nationalist politics, which ran counter to Mao’s insistence that class struggle was the only viable solution to racial oppression, Williams’s condemnations of “Soviet revisionism” garnered him a degree of trust from his Chinese hosts. In reference to a brief stay in Moscow, Williams expressed that “the people there knew very little about [our] struggle, and in speaking with African students in the Soviet Union, we found that they hadn’t heard of the murders in Birmingham. The Soviets moved news of this struggle to the backburner.”

As a result of his differences with Cuba, Williams relocated his family to Beijing, where they lived from 1966 to 1969. During this period, conflicts between Williams and the Maoist vision of race, class, and minority nationalism surfaced time and again. They were, in a sense, a reiteration of the fraught relationship between black liberation and socialist internationalism since the early twentieth century. Black Power activists like Williams grounded their visions of anti-imperialist solidarity in racial nationalism and co-identification. But while Chinese officials sought to distinguish themselves from perceived Cuban and Soviet shortcomings on the question of race, they deployed their comparative sensitivities to racial issues only to legitimate their advocacy of class struggle as the bottom line.

[1] “美国黑人领袖罗伯特威廉接待工作小组谈论提要 [Discussion Notes from Working Group for Receiving African American Leader Robert Williams],” File No. C36-2-175-195, Shanghai Municipal Archives (SMA), Shanghai, China.

[2] “中国人民保卫世界和平委员会上海分会关于接待罗伯特威廉夫妇的计划, 主要问题请示决定记录, 日程, 情况汇报, 新闻报导, 小结讨论摘要等 [Plans, Record of Decisions Regarding Important Questions, Itineraries, Reports, News, and Summaries of the Chinese People’s Association for World Peace, Shanghai Commission’s Reception of Robert Williams and His Wife],” File No. C36-2-175, SMA.

[3] Robert Williams, “Hallelujah: The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth,” The Crusader (October 1964), p. 9.

[4] “接待美国黑人领袖罗伯特威廉全家的计划 [Plan for Receiving African American Leader Robert Williams and His Family],” File No. C-36-2-215, SMA.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more