Sino-Soviet Nuclear Relations: An Alliance of Convenience?

China backed Soviet disarmament proposals in exchange for technical assistance in nuclear weapons development. When Soviet aid stopped, so did China’s support.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

China backed Soviet disarmament proposals in exchange for technical assistance in nuclear weapons development. When Soviet aid stopped, so did China’s support.

China backed Soviet disarmament proposals in exchange for technical assistance in nuclear weapons development. When Soviet aid stopped, so did China’s support.

On December 10, 1957, the Government of the Soviet Union proposed that the United States, Great Britain, and the USSR halt nuclear weapons tests for the next two to three years. In an official statement released days later, the Chinese Government expressed its full support for the Soviet proposal, stating that a temporary test ban would help reduce mounting tensions worldwide.

Yet only three years later, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs disputed a similar Soviet proposal. At the 15th General Assembly of the United Nations held in September 1960, Nikita Khrushchev stressed the urgency of complete global disarmament. In a cable dispatched to the embassy in Moscow and copied to all Chinese missions abroad on October 14, the Foreign Ministry claimed that China could not possibly agree with Khrushchev’s proposal for complete disarmament while “imperialism” still existed in the world. The 180-degree turn in China’s tone toward the Soviet disarmament proposal—as revealed by these two Chinese documents cited above and now accessible on DigitalArchive.org—reflects overall changes in Sino-Soviet nuclear relations in the late 1950s.

From the outset, Sino-Soviet nuclear cooperation was marked by political expediency on both sides. From 1949 through the late 1950s, the People’s Republic of China saw the danger of nuclear war escalate as the United States issued atomic threats against China during the Korean War and the Taiwan Strait Crisis from 1954 to 1955. Moreover, since its victory in the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese Communist Party had been fighting against the West’s refusal to accept the PRC as the legitimate representative of China at the United Nations. Mao assumed, according to Nicola Horsburgh Leveringhaus, that having nuclear weapons would raise China’s standing on the international stage and protect it against Western “imperialist bullying.”

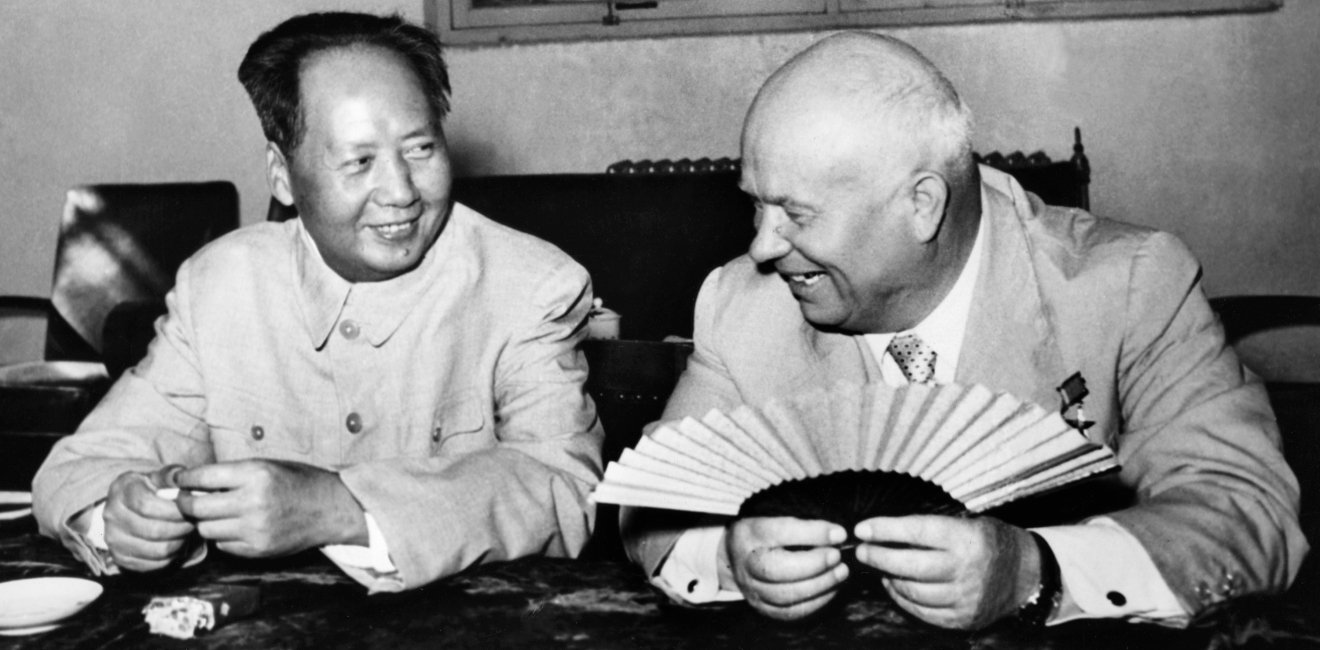

As China’s interest in developing nuclear weapons grew, it sought technical expertise and assistance from its chief ally, the Soviet Union. Nikita Khrushchev was initially reluctant to share nuclear technology with China, since it could have eroded the Soviet Union’s military superiority within the socialist bloc. But in 1954, as Zhihua Shen and Yafeng Xia argue, Khrushchev ultimately agreed to assist China with the development of an atomic energy program because he needed Mao’s political support in the post-Stalin struggle for leadership inside of the CPSU. In return, China publically aligned with the Soviet Union’s stance on disarmament and nuclear non-proliferation. Thus, until the late 1950s, China publicly supported the Soviet Union’s disarmament proposals, even as it sought to push its own nuclear weapons program forward.

However, the relationship between the two socialist allies soured in the latter half of 1950s. The PRC’s confrontational stance in its international dealings, evident in its assault on the islands of Quemoy and Matsu in 1958, provoked tensions with the United States as well as with the Soviet Union. As the United States increased its military presence in the Taiwan Strait, the Soviet Union grew concerned over a potential conflict in the region.

The fact that the Chinese Government did not consult with the Soviet government prior to its attack on the islands—and that the Moscow had to share responsibility for Chinese actions, whatever the outcome—displeased Khrushchev greatly. Mao Zedong’s pursuit of domestic and foreign policies which clashed with Soviet advice and interests, such as launching the Great Leap Forward and escalating the Sino-Indian border dispute, further strained the Sino-Soviet alliance.

The growing schism between Beijing and Moscow in the late 1950s prompted the latter to steadily reduce its technology transfers to China, culminating in the recall of all Soviet experts from China in 1960. The Soviet Union’s assistance to China’s nuclear weapons program likewise came to an abrupt halt.

The Chinese Government’s 1957 statement and the Foreign Ministry’s October 1960 cable encapsulate changes in Sino-Soviet nuclear relations in the 1950s and 1960s. While China was receiving nuclear technology from the Soviet Union and developing its own nuclear weapons program, it publicly supported the Soviet Union’s calls for disarmament. When Soviet aid ended in 1960, the Chinese Government no longer felt obligated to support Moscow's proposals for test bans and arms reductions.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more