The Soviet-Chinese Spy Wars in the 1970s: What KGB Counterintelligence Knew, Part I

Filip Kovacevic analyzes the “subversive activities” of the Chinese intelligence services in the 1970s as seen from the eyes of the Soviet KGB.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Filip Kovacevic analyzes the “subversive activities” of the Chinese intelligence services in the 1970s as seen from the eyes of the Soviet KGB.

Editor’s Note: The following article and analysis is adapted from an earlier posting on The Chekist Monitor, a blog by Dr. Filip Kovacevic providing analyses and translations of Russian-language sources concerning the history of Soviet/Russian state security and intelligence organizations. – Charles Kraus

In her studies of Chinese espionage in Switzerland during the Cold War, Ariane Knüsel points to the fact that there is little archival research on the subject, mainly because most Western countries still keep files on the Cold War activities of Chinese intelligence services classified.

The situation appears to be different in some countries of the former Soviet bloc. In the Baltic states and Ukraine, the files of the vast Soviet state security apparatus and its primary representative, the Committee for State Security (KGB), are increasingly accessible to intelligence historians and other scholars, with many sources having even been digitized and posted online.

One of the organizations engaged in this effort, the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania (GRRCL), has done a remarkable job of making the files of the territorial (regional) unit of the KGB in Lithuania available to the wider public. Its online holdings include the top secret journals of the KGB which shed light both on the internal functioning of the KGB as well as on its methods, sources, and operations. Used for internal communication, the sharing of professional experiences and expertise, and building up the common Chekist identity and esprit de corps, these journals can, metaphorically speaking, be perceived as the “brain of the KGB.”

The journals include the issues of the bi-monthly (later monthly) periodical KGB Sbornik [Review] and the semi-annual volume Trudy [Papers] of the Felix Dzerzhinsky Higher School of the KGB.[1] While the GRRCL collection of these journals is not complete, it is still the most extensive collection available to the public at this time. It contains almost all of the issues of the KGB Sbornik from 1985 until 1990 (No. 101 – No. 146-147) and about half of the volumes of the Papers from 1971 until 1989 (Vol. 2 – Vol. 45).[2]

Most articles in both the KGB Sbornik and the KGB Papers deal with the subject of counterintelligence, though there are some that cover legal issues and intelligence history. The KGB Sbornik had a much wider distribution than the KGB Papers (which printed only 350 copies per volume in the 1980s) and the language of its articles was less bureaucratic. The KGB Sbornik sought to increase the number of its regional contributors and often published short articles on the various issues of the day impacting on the KGB activities across the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, the KGB Papers generally published longer research articles based on the top secret operational files of the KGB. They were typically written by the instructors and graduate assistants of the Higher School of the KGB, or by the high-level officers in the KGB territorial units. My analysis here and in several follow up articles is based on four articles from the KGB Papers published in the four-year time period, from 1978 to 1982.

Casual readers of the KGB Papers might be surprised by the number of articles dealing with what their authors called the “subversive activities” of the Chinese intelligence services, considering that the West (and especially the US) was designated by the Soviet Union as the “main adversary.” However, the prevalence of these articles indicates that after the Sino-Soviet ideological split in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the KGB considered the Chinese Maoist regime just as hostile and threatening to Soviet national interests as Western democracies.[3] In fact, most articles in the KGB Papers are prefaced by the resolutions and statements of the various Congresses of the Soviet Communist Party which, in no unclear terms, condemned the direction of Chinese government’s foreign and domestic policies in the 1960s and 1970s.

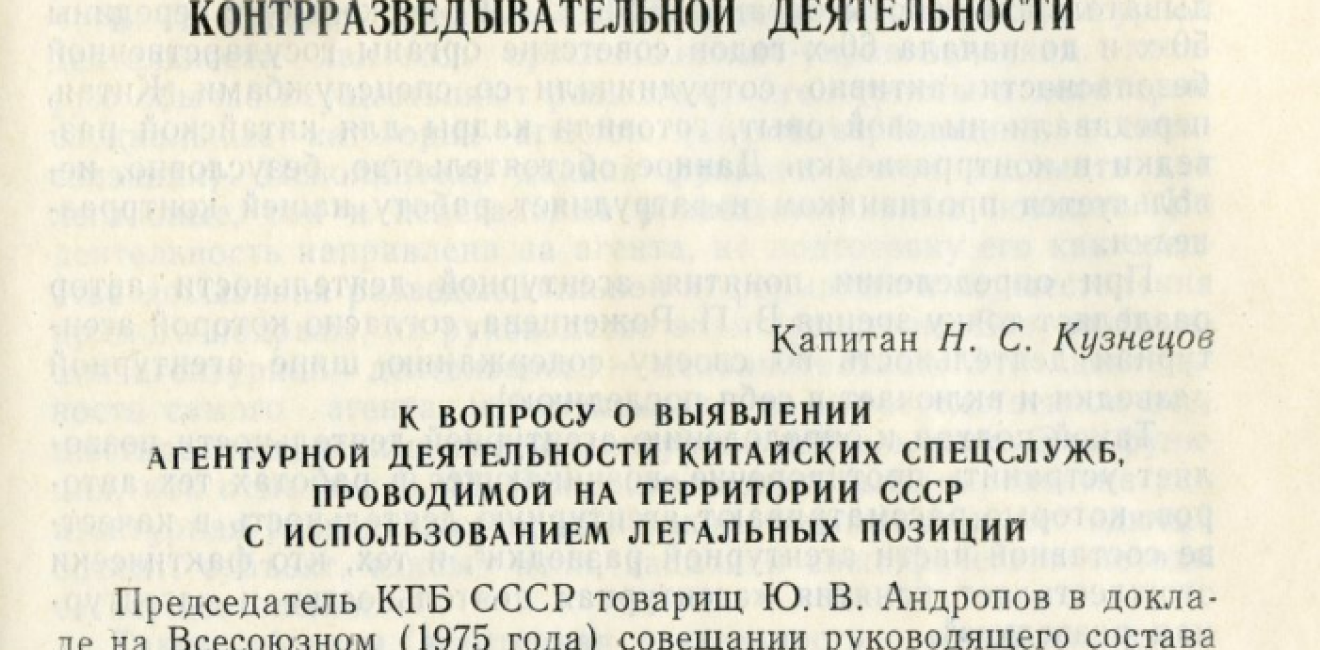

One of the most revelatory articles along these lines was written by KGB counterintelligence officer Captain N.S. Kuznetsov and published in 1980. Titled “Toward the Question of the Detection of the Activities of Chinese Intelligence Services Using the Legal Cover on the Territory of the USSR,” the article presents the KGB’s Second Main Directorate (Counterintelligence) insights about the operations of the legal officers of Chinese intelligence agencies in the USSR in the 1970s.[4]

The article has never been officially declassified by the Russian government and is analyzed here in English for the first time.

Kuznetsov begins by referring to the 1975 speech of the KGB chairman Yury Andropov, who stated that the subversive activities of Chinese intelligence in the USSR represented a threat to state security. Accordingly, Kuznetsov refers to China as the “adversary” throughout the article. (Note that, at the same time, the United States was referred to as the “main adversary.”)

Kuznetsov focuses on the Chinese intelligence officers who operate in the Soviet Union under the diplomatic cover. According to him, these officers are based at the Chinese Embassy in Moscow, the headquarters of the Chinese state news agency (Xinhua), and the Chinese civil aviation office at the Moscow Sheremetyevo airport, which was located in the Siberian city of Irkutsk until 1974. In addition, Chinese intelligence also has its personnel in the trade and border guard delegations in the border towns of Zabaikalsk and Grodekovo as well as on the Beijing-Moscow railway line. However, Kuznetsov stresses that the main controlling post of Chinese espionage in the USSR is the Chinese Embassy, which houses both the officers of the Chinese state security and foreign intelligence service and the Chinese military intelligence service.

Kuznetsov characterizes the Chinese intelligence officers as extremely cautious and circumspect in their dealings with Soviet citizens. He states that they are well-trained in Russian language and often successful in avoiding KGB surveillance. According to Kuznetsov, their favorite recruitment opportunities are the diplomatic events and parties organized by the Chinese Embassy. He notes that, in the period from 1972 to 1976, the Chinese Embassy organized more than 60 events with the participation of about 2,500 foreign citizens, 1,000 Soviet citizens, and 400 Chinese permanent residents in the Soviet Union. The Chinese permanent residents as well as other members of the ethnic Chinese community in the USSR (Kuznetsov estimates their number at 250,000) have traditionally represented the largest pool of recruits for Chinese intelligence. However, he emphasizes that the recruitment only takes place after a lengthy process of checks and controls, including the unannounced visits to the places of residence, and typically takes years.

Kuznetsov enumerates the following signs that the Chinese intelligence has begun paying attention to a particular Chinese permanent resident living in the USSR: frequent invitations to the Embassy events, always being received by the same Embassy official, gifts (national souvenirs, small amounts of money), and inquiries about him or her via other channels. He states that while it is possible for the KGB to dangle its undercover agent from the Chinese community for recruitment, it requires an air-tight cover story, including real-life family connections to China. The KGB agent must also be ready for extensive questioning by Chinese intelligence officers. Kuznetsov also warns that Chinese intelligence officers are very suspicious of all volunteers.

According to Kuznetsov, the most effective way to infiltrate a KGB agent into the Chinese espionage network in the USSR is to use the existing KGB agents among the non-Soviet diplomats and journalists from developing and even “capitalist” countries. He emphasizes that the Chinese intelligence officers have shown themselves to be very active in trying to recruit from this group, in addition to recruiting from the Chinese immigrant community. He also notes that the partner counterintelligence services of Mongolia and East Germany have come to the same conclusion.

In addition, no matter how guarded and cautious the Chinese Embassy officials appear to be, Kuznetsov notes that the KGB counterintelligence is on a constant lookout for their potential moral failings and compromising behavior. For instance, he chronicles a visit of two Chinese diplomats known only under the initials “Ch.” and “M.” to Irkutsk in 1969 when one of them behaved immorally (he leaves out the specifics of what the official did). In addition, Kuznetsov mentions that some Chinese trade officials visiting the border town of Grodekovo were observed by the KGB agents stealing money and souvenirs from each other. He underscores that these and similar situations can be used as counterintelligence recruitment tools.

Kuznetsov describes several actual cases of the Chinese recruitment of Soviet citizens. The first case is that of the Chinese language translator codenamed “Monk” trying to recruit the Soviet translator codenamed “Mole” (not a very creative code name, I know). “Mole” worked as a translator in the Chita region from 1954 until 1961 and was demoted for alcoholism. His personal and career failings were used as a recruitment tool by the Chinese intelligence. In the period from 1972 to 1974, “Mole” was asked to supply the Chinese with classified information about Soviet military and industrial infrastructure and was promised monetary gifts and even exfiltration to China. Obviously, “Mole” operated under the control of the KGB and was giving the Chinese intelligence useless information or misdirecting them.

The second case described by Kuznetsov is that of the airport official codenamed “Rogov” whose recruitment was attempted while the Chinese civil aviation office was still located in Irkutsk. “Rogov” was being checked and re-checked by the Chinese for two years while being asked to read Maoist political pamphlets and discuss them with his handlers. He was also asked to write an anti-Soviet article for a Chinese newspaper. Just like “Mole,” he too was under the control of the KGB.

Kuznetsov also discusses the case of the Chinese spy known only under the initial “Ch.” Ch. came to one of the regional KGB headquarters in 1975 and voluntarily confessed that he was spying for China. Already a permanent resident, Ch. stated that he was recruited by the Chinese intelligence before his arrival to the USSR and began spying in 1961. For more than a decade, he performed secret assignments by the intelligence personnel based at the Chinese Embassy. He stated that he would typically meet with them in the Embassy car or that he would be covertly driven into the Embassy compound. Ch. also said that, if needed, he would communicate with the Chinese intelligence officers via phone using coded messages. Kuznetsov does not indicate anything about Ch.’s ultimate fate. It seems likely that Ch. was turned into a double agent and may still have been operating when the article was written.

In conclusion, Kuznetsov admits that the issue of Chinese espionage in the USSR is a complex one and calls for the compilation of all available data (historical and operative) in one place in order to create a general model of Chinese intelligence activities. He claims that the existence of such a model would not only allow the KGB counterintelligence to avoid mistakes in planning its operations but would also make it possible to deal “pre-emptive blows” to the Chinese intelligence services, if and when necessary.

As we can see, the animosity between the Soviet and Chinese intelligence services was running high in the 1970s. The KGB counterintelligence seems to have had notable successes and yet, at the same time, it exhibited a degree of insecurity making it seem as if the Chinese were able to gain some hard to define, but tangible advantage in the spy war. Kuznetsov tries to sound hopeful, but there is hidden anxiety subsumed in his narrative.

The next post analyzes another article in the same volume of the KGB Papers which also focuses on the activities of the Chinese intelligence services in the Soviet Union but includes additional information not provided by Kuznetsov.

[1] About 30 issues of the KGB Sbornik were briefly analyzed by Victor J. Yasmann and Vladislav M. Zubok in their 1998 research study for the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research. See Victor Yasmann, “The KGB Documents and the Soviet Collapse: A Preliminary Report” (Washington, DC: The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, 1998); Victor Yasmann and Vladislav Zubok, “The KGB Documents and the Soviet Collapse: Part II” (Washington, DC: The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, 1998). The most recent research use of the KGB Sbornik can be found in Sanshiro Hosaka (2020) “Repeating History: Soviet Offensive Counterintelligence Active Measures,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence (2020). On the other hand, as I far as I know, the Papers of the Higher School of the KGB have not been analyzed before this study.

[2] The missing numbers of the KGB Sbornik are No. 106 and No. 111, while the KGB Papers collection is missing Volumes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 24, 25, 32, 33, 34, 35, 40, 41, 42, 44.

[3] Zhihua Shen and Yafeng Xia. Mao and the Sino-Soviet Partnership, 1945–1959 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015).

[4]Капитан Н. С. Кузнецов, “К вопросу о выявлении агентурной деятельности китайских спецслужб, проводимой на территории СССР с использованием легальных позиции.“ Труды Высшей Школы 21 [Papers of the Dzerzhinsky Higher School of the KGB, Volume 21]. Moscow, 1980, pages 203-216. Classified as Top Secret.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more