The Soviet Union and the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Sayuri Romei examines Soviet records produced in the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the continuing importance of Hiroshima to Russian foreign policy.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Sayuri Romei examines Soviet records produced in the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the continuing importance of Hiroshima to Russian foreign policy.

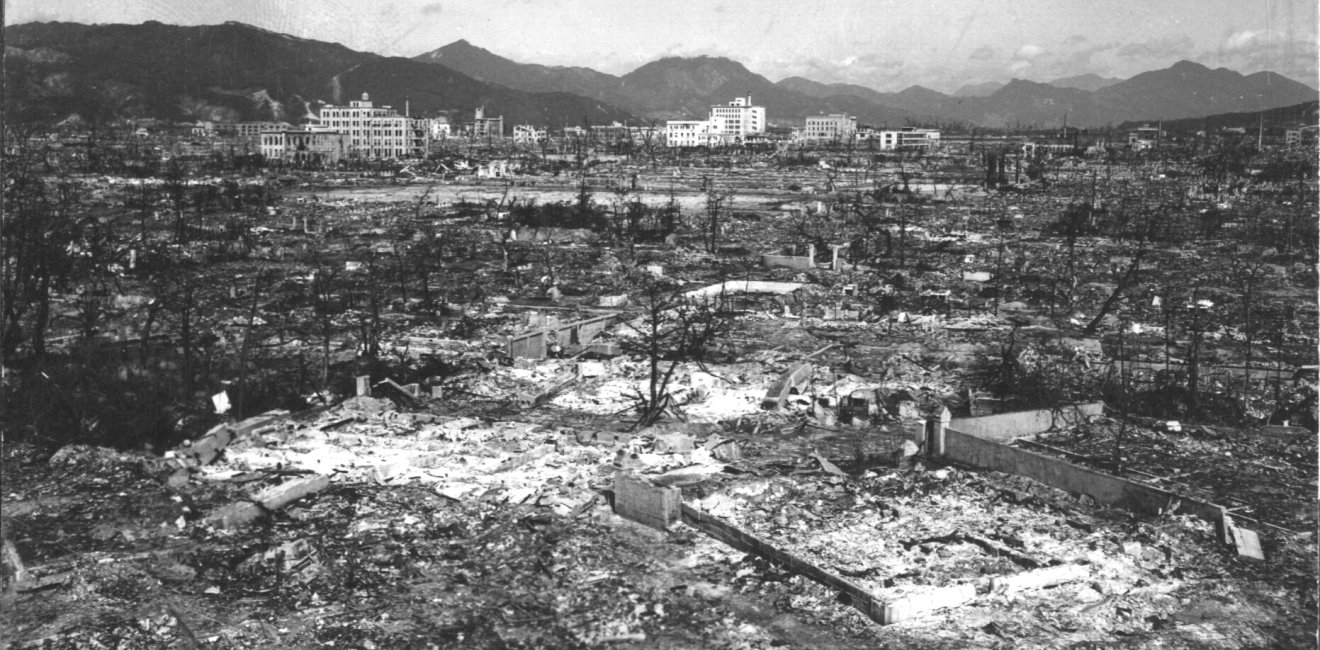

"Nobody should allow themselves to forget the tragedy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki," declared Sergey Naryshkin on August 5, 2015, at an event at Moscow's State Institute of International Relations commemorating the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings on the Japanese cities. Naryshkin, then Chairman of the State Duma and Director of the Russian Historical Society, also added that if those responsible for the bombings were not punished "there could be very, very serious consequences."

As this August marks the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we are once again urged to reflect on the political role of the weapon that inaugurated the Nuclear Age.

The documents introduced here were published in Russian for the first time in 1990, and the English version was included in an issue of the Soviet journal International Affairs (1990, no. 8).

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs brought renewed attention to these documents more recently on August 5, 2015, the same day Naryshkin was pointing a finger at the United States in his speech. Although they have been public for 30 years, new translations of these sources are now freely accessible on the Wilson Center’s Digital Archive. My analysis will provide some historical and political context and offer an initial assessment of these documents.

In writing to the Soviet leadership, Soviet Ambassador to Japan Iakov Malik included a nine-page report resulting from a trip to Hiroshima and Nagasaki by a group of staff members sent by the Soviet Embassy in September 1945. The document was then circulated on November 22, 1945 by Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov to Stalin, Lavrentyi Beria (at that point appointed as head of the Soviet atomic bomb project), and Politburo members Georgy Malenkov and Anastas Mikoyan.

Before summarizing the findings of the embassy mission, Malik offered the premise that the report was limited to a recording of conversations and personal impressions “without any kind of generalizations or conclusions.” However, it is clear from the beginning that this report had the objective of minimizing the effects of the atomic bomb. The first paragraph mocks the Japanese press for exaggerating the aftereffects of the explosion, for giving in to “popular rumor” that takes press reports “to absurdity.” The Soviet report suggests that the exaggeration of the Japanese press stemmed from Japan’s attempt to save face in light of the defeat.

In fact, after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, the Japanese military’s Information Division, in charge of media control, intended to announce that the bomb was an atomic one. However, the Department of the Interior opposed the disclosure of the nature of the weapon. That is why, on August 8, Japanese newspapers first reported that “the enemy used a new type of bomb in attacking Hiroshima, but the details are still under investigation.”

The phrasing “a new type of bomb” (新型爆弾 shingata bakudan) was used because the expression “atomic bomb” (原子爆弾 genshi bakudan) was prohibited by the Japanese government during the war. The ban on the public use of the phrase was officially lifted when the war ended on August 15, which prompted Hiroshima’s local newspaper, the Chūgoku Shimbun, to print a few photos of the destroyed city on August 23. The weekly illustrated magazine Asahi Graph also published a brief article on August 25 titled “What is an atomic bomb?”

However, as soon as the Allied occupation of Japan came into force on September 19, the strict press code imposed by the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, as well as the above-mentioned self-censorship imposed by the Japanese press, caused a delay in the way the atomic bombings were reported upon in Japan. Moreover, the atrocities of the bombs were not made graphically public to the Japanese people until August 6, 1952, when Asahi Graph published the issue titled “Genbaku higai no shokōkai” (the first publication of the damages of the atomic bomb). Therefore, it is hard to believe that by November 1945, the Japanese press had any detailed, spontaneous reporting of the effects of the atomic bomb.

The parts that are highlighted in the report with a line on the left-hand margin are noteworthy. None of these sections are about damage to human beings. Rather, they are mostly about damage to inanimate objects. They note large scale destruction of the city and damage to buildings (the hospital, gas storage tanks, the Mitsubishi plant, etc.) and offer details on potential protection (“protective clothing against a uranium bomb includes rubber and any kind of insulation against electricity”). Some of the highlighted parts even emphasize signs of life (“contrary to all the evidence, we saw how in various places the grass was beginning to turn green and even on some scorched trees new leaves were appearing.”).

Such details and information may have been useful for the Soviet atomic bomb project, pushing the internal narrative that the USSR needed its own weapon as soon as possible. However, it is striking that none of the people sent to ground zero in the immediate aftermath of the bombings were scientists or technicians. The embassy teams included GRU members Mikhail Ivanov and German Sergeev in August, and TASS correspondent Anatoliy Varshavskiy, former acting military attaché Mikhail Romanov, and Naval apparatus employee Sergey Kikenin in September. Most of these individuals were bureaucrats, which also explains the lack of scientific terms and technical observations on the effects of radiation. Until 1949, when the USSR succeeded in testing its own bomb, the Soviet Union’s knowledge of the effects of radiation was indeed very poor. The non-specialist staff sent to observe these effects, their biased premise, and the markings on the documents all suggest that the report was from the beginning meant to anticipate and align with Stalin’s intention to downplay the importance of the United States’ atomic bomb while pushing the Soviet Union’s own nuclear project forward.

The timing of the trip to Hiroshima and Nagasaki within 40 days of the bombings illustrates the Soviet race to obtain its own atomic bomb, but the timing of the 2015 re-release of these documents is also significant: it came at a time when US-Russia relations were suffering a major deterioration. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in February 2014 escalated tensions between Washington and Moscow and changed the global perception of Russia’s role in international politics. Russia’s military intervention in Syria and Putin’s speech at the 70th UN General Assembly in September 2015 further aggravated the US-Russia bilateral relations.

In this context, Naryshkin’s words gain a particular nuance: the anniversaries of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were an excellent opportunity for Moscow to revive its relationship with Tokyo, which irritated US officials at a time when the United States sought a united front with its ally in light of Russia’s increasingly aggressive behavior. Moscow’s opening to Japan in 2015 then engendered a shift in Japan-Russia relations, as confirmed by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s visit to Tokyo in April, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s bold visit to Moscow in May and Naryshkin’s visit to Tokyo in June 2016, right after President Obama’s historical visit to Hiroshima at the end of May.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki represent the point of no return in the history of world politics: they mark the dramatic culmination and end of the war, while symbolizing the beginning of an era of nuclear fear. The message that the bombings sent to the world was that whoever possessed those special weapons would prove to be politically superior, thus turning such weapons into the passport to survive and potentially win the Cold War. Seventy-five years later, and with the Doomsday Clock closer to midnight than ever, it is essential to keep exploring the meaning of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and how these tragedies still shape current global politics.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more