Strategic Gossip

Alex Bollfrass gets the story straight on Germany’s nuclear ambitions.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Alex Bollfrass gets the story straight on Germany’s nuclear ambitions.

Getting the story straight on Germany’s nuclear ambitions

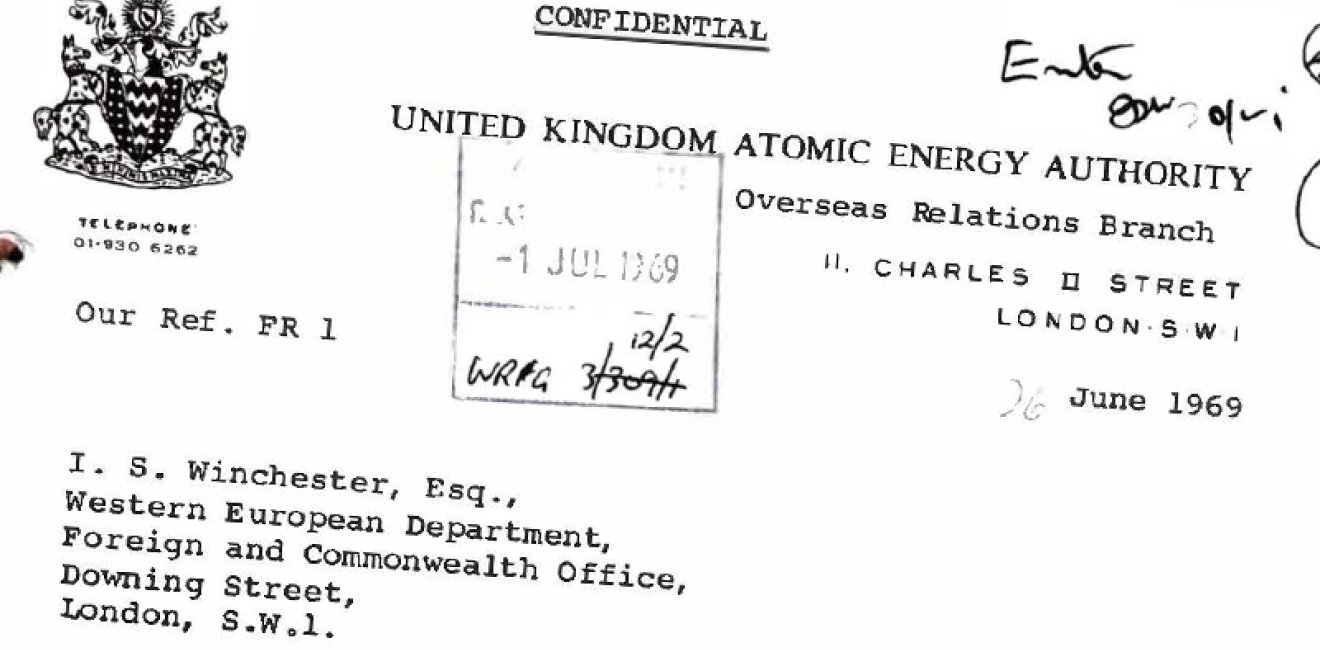

On March 19th, 1969, alarm spread through the British security establishment. Rumors of West German nuclear weapons ambitions could no longer be dismissed as Warsaw Pact propaganda. Highest-level French officials warned of their common ally's secret plutonium reprocessing projects. One advisor of President de Gaulle was quoted:

"I can tell what they are really after, what is really in the back of their minds, is a national force de frappe. Look how keen they are on everything to do with military aircraft, and rockets—all the strategic sectors. It's all part of the same thing. Call it "gaullism", if you like but gaullism in somebody else's country isn't quite so pleasant, alas."

What did the French know that the British had missed? Alarmed, the UK Joint Intelligence Committee tasked the Directorate of Scientific and Technical Intelligence and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office with a bottom-up review of all available indicators that the Germans were preparing to develop their own force de frappe. After months of analysis, the draft technical report concluded:

“There is no evidence that [West Germany] is engaged in a military nuclear programme, and we believe that it would currently be difficult on technical grounds for her to do so, even if she wished, which must at present be extremely unlikely.”

Unable to find even the slightest indication that the Federal Republic was a candidate for proliferation, British analysis turned to speculation about French motivations in spreading these allegations. A diplomat in Bonn expressed his conspiratorial view about the French rumor campaign, arguing that it was a way of preventing British-German cooperation in developing centrifuge technology for uranium enrichment.

Another FCO memo on the false alarm described an "apparent psychological gap in the Elysée mind":

"[O]n the one hand, almost pathologically distrustful of German nationalism, and on the other persists in the very policies likely not only to promote such nationalism—by example of no other way—but also to prevent the obvious means of its containment, the pressure of Britain in a unified Western Europe. If all his intimate minions are equally affected by the particular kind of mental blindness, it is less hard to understand why the obvious is never brought to the General's notice. It does not seem obvious to them either."

But perhaps French smoke did indicate a German fire: recent political science has given French concerns more credence.

The chart below, from a working paper with Darren Lim of Australian National University, contrasts how major contemporary studies of nuclear proliferation have coded the German case, with a 0 indicating no pursuit of nuclear weapons, a 1 its opposite.

Among the above codings, Bleek and Lorber seem closest to the available historical evidence.

After the war, German rearmament was strictly controlled: first by the occupying Allies, then by West Germany's pledge to its NATO allies not to pursue WMD weapons in 1954. American troops in Germany eventually were equipped with nuclear weapons, where some remain to this day. Germany sought greater say in how these weapons would be used in the event of war and may have briefly explored participation in the French nuclear program in 1959.

To preview a work in progress, Lim and I conclude that these exaggerated conclusions of a willingness to acquire nuclear weapons came about for three reasons. First, the researchers only report confirmatory evidence on narrow indicators. Second, they conflate allied nuclear projects with independent ambition. Finally, the studies combine plausible German intent from the 1950s with the nuclear energy capabilities that emerged a decade later.

By contrast, Jonas Schneider’s recent book demonstrates how much of the relevant German documentation is in fact available in the country’s archives. The difficulty political science has in converging on a common coding of the nuclear weapons intentions of a transparent democracy is disheartening.

What's at stake in this academic dispute? Beyond my parochial interest in needing a correct assessment of German nuclear weapons intentions for my dissertation, Germany is one of the most important and widely studied examples of nuclear forbearance in the academic literature. Its history is often evoked in arguments for specific policies the US should use to prevent its allies from building their own nuclear arsenals.

Further, as Marc Trachtenberg shows in his book A Constructed Peace, Soviet concerns about the possibility of nuclear-armed Germany propelled hostility in the early Cold War. These same concerns also paved the way toward the negotiation of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty as a means for locking in Germany's nuclear abstention.

Finally, understanding how the era’s policymakers and today’s academics misinterpreted Germany's proliferation potential in the 1950s and 1960s can help us interpret recent news that some Germans are re-examining the country’s nuclear options. As in the Cold War, these conversations are more about Germany’s security relationship with the United States than early warning signs of a German bomb.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more