The “Kindness” of Stalin

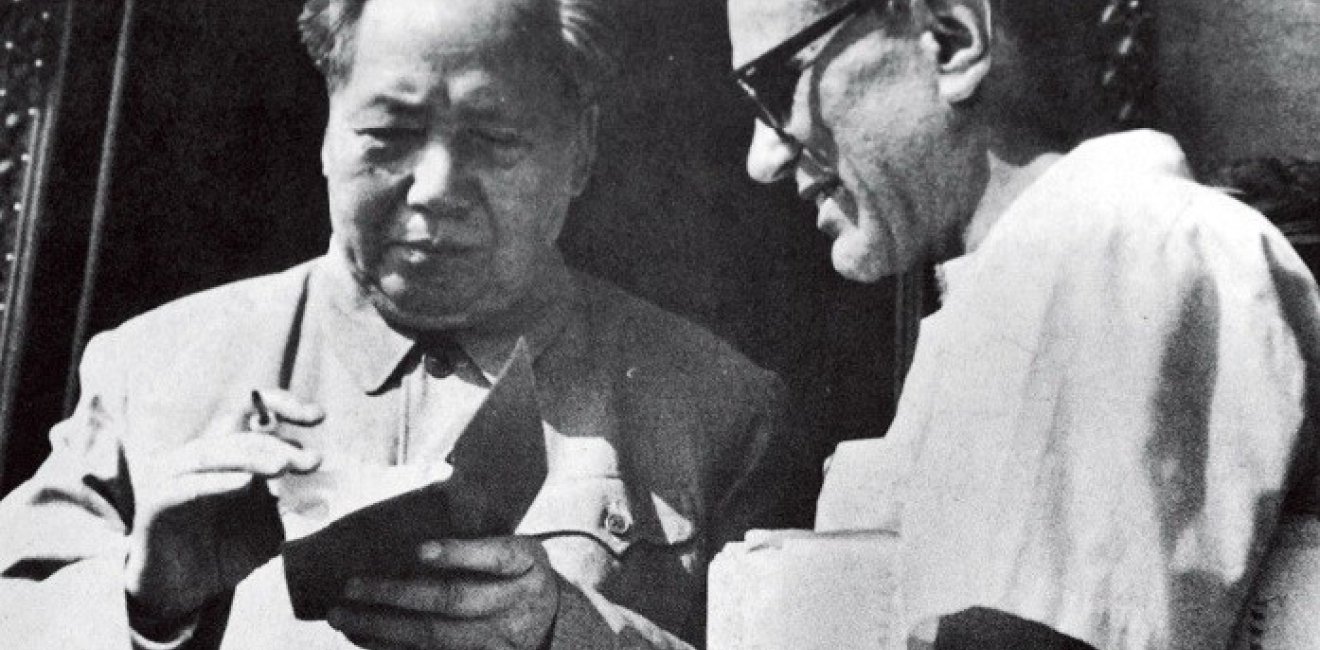

Sidney Rittenberg reacts to Soviet evidence showing it was Stalin who ordered his imprisonment.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Sidney Rittenberg reacts to Soviet evidence showing it was Stalin who ordered his imprisonment.

Sidney Rittenberg reacts to Soviet evidence showing it was Stalin who ordered his imprisonment

We do not doubt that the American Rittenberg…is a vicious American spy. We advise to arrest him immediately and, through him, to expose the network of American agents – Joseph Stalin, February 4, 1949

I always assumed—and I believe the Chinese Communist Party leaders also believed—that I was arrested in 1949 primarily as a close associate of US writer and journalist Anna Louise Strong. Chairman Mao personally confirmed this in Shanghai in November 1965, when he expressed regret about her deportation from the Soviet Union in 1949 as an “American spy.” Mao waved at me, and said to his Chinese colleagues, “And you involved him too, and he sat in the guard house.” (“Guard house,” or ban fang, was a euphemism for prison.)

From the available Soviet archival documents, however, it appears that Stalin's demand to arrest me predated Strong’s deportation. Moreover, in the mid-1980s Mao’s former secretary and Chinese Politburo member Hu Qiaomu was reported to have said that my arrest was not because of Strong, so it seems that he knew something that Mao chose to forget, although Mao’s memory for detail was phenomenal.

Was Strong’s expulsion also part of the same investigation of someone “blabbing” that trapped me? Who knows. What Strong told me after being cleared and returning to China in 1958 was the following: she was on her way through Moscow back to Beijing. The night before she was to continue on to Beijing, she was invited to dinner by her “friend,” a Soviet Vice Foreign Minister. During the casual chit-chat over the dinner table she was asked what she thought of Tito, who had been denounced in the harshest possible terms by Moscow. In the US, Strong had just published a long, glowing anthem to Tito’s socialism. But in Moscow she answered that, in case of a conflict between the USSR and Tito, she would have to support the USSR, because the latter was leader of the socialist camp, while Yugoslavia was a minor player. Then, said Anna Louise, her “friend” asked what her position would be if the USSR should split with Mao Zedong, as it had with Tito. Her answer was that she would have to support Mao Zedong, because the Soviet Union showed signs of bureaucratization and stultification, while the vast social experimentation going on in China was most important for the future of humanity. The next morning, around 5:30, she was arrested, and denounced and expelled a few days later.

A final detail: On the morning of my sudden arrest, I was first summoned to the dwelling of Xinhua News Agency Chief, Liao Chengzhi, a close friend. I was ecstatic at the belief that I was being sent on a special mission to Beijing to help with liaison between Washington and the Communist government. While I was at Liao’s place, one of the editors rushed in excitedly to read aloud the TASS News Agency bulletin about the arrest and expulsion of the “notorious American spy,” Anna Louise Strong.

I was in such a euphoria about my “special mission” that I had no room to emote seriously over the news bulletin, but Liao, when he escorted me to Shi Zhe’s jeep that carried me off, gave me a big hug (not a usual Chinese gesture) and said, as though comforting me, “Don't worry, Little Foreign Devil (my nickname), it’ll all work out in the end. Just don't be like Liu Bei when he entered Jingzhou!”

I wondered briefly why he was saying that something would “work out in the end,” but I am not a suspicious type and the thought that I might be headed for a pitch-black solitary cell never entered my head.

Finally, after one year in solitary darkness, the warden of the prison, Yao Lun, informed me that the charges against me were cancelled, that they understood me, but they couldn't let me go until my case was settled. I could either stay there (with the windows unboarded and the cell lighted) and study, for which they would provide books of my choice and writing materials, or I could go back to America and forget about China. I chose to stay, to study and to work on recovering from severe PTSD. By this time, I understood that it was because my problem was with Moscow, not with Beijing.

As for not being like Liu Bei when he entered Jingzhou, I couldn't for the life of me remember that episode from the “Tales of the Three Kingdoms,” and I didn't know what Liao was trying to tell me until I asked him seven years later. “I was saying, ‘Don't go to pieces’,” was his answer.

I still never dreamed that I had attracted the personal attention of Joseph Stalin, himself.

It was, of course, only because Stalin was kind enough to die in 1953 that I was set free in 1955.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more