The history of decolonization, of South-South cooperation, of the Global Cold War, and of the North-South conflict cannot be grasped without understanding the crucial impact and changing fate of the Non-Alignment Movement.

Despite opposition from the former European colonial powers and the superpowers of the East-West conflict, governments from nearly all Asian, African, and Latin American countries—with very different political and economic systems—still banded together in the Non-Aligned Movement.

In my recent book, The Non-Aligned Movement: Genesis, Organization and Politics (1927-1992), I expose how the NAM became a new actor in international politics. Institutionalized in the 1970s, it played a significant role in both the North-South conflict and the development of South-South relations. Until today, it claims to champion the interests of the “Non-Aligned,” or the “Global South”, on the international political stage. The movement induced a permanent expansion in the ensemble of actors participating in international relations and, after the United Nations, represents one of the largest international organizations of our time.

In The Non-Aligned Movement, I examine the history of the NAM since the interwar period as a special reaction of the “Global South” to changing global orders. Against this background, the study recovers the ruptures and continuities in the history of twentieth century globalization by approaching the history of international relations from a non-western perspective that allows for problematizing Eurocentric interpretations of the 20th century.

The book takes up ideas that have been discussed for around a decade, since the discipline of international history has tilted on its axis and a global historiography has begun to get off the ground—not only “bringing the South” in, but challenging established assumptions about centers and peripheries in international relations. This book puts these claims into practice through an empirical analysis that inquires when and why the Non-Aligned Movement was established and emerged as a new international player.

In contrast to previous research that has largely been fascinated with the history of non-aligned countries in the 1950s and 1960s, the book shows that it was not until the 1970s that the NAM actually emerged as an institutionalized movement.

Even more so, the NAM actually had its heyday during the North-South conflict, when it arose as an important actor in international politics.

The NAM was thus not merely the product of an era during which many new international institutions came into being, but also a protagonist that precipitated further international institutionalization.

The book furthermore demonstrates that the global context in which the NAM emerged was that of the conflict between North and South and not between East and West. In this confrontation it claimed to speak on behalf of the Global South and advance its interests. And indeed, the West recognized its role in this regard.

The lack of a consolidated archive of the NAM posed a particular challenge for this study. Empirical research for the book was undertaken in Germany, Great Britain, Indonesia, Russia, Serbia, and the United States.

To trace early efforts to institutionalize anti-colonial resistance across or beyond empires’ boundaries (in particular in the League against Imperialism), the holdings of the Antiimperialističeskaja Liga in the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI) in Moscow were particularly valuable. In addition to the League Secretariat’s correspondence with anticolonial activists from all over the world, such as Mohammad Hatta, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Jomo Kenyatta, this archive provides numerous internal reports and discussion papers and hence manifold insights into the League’s structure and strategy.

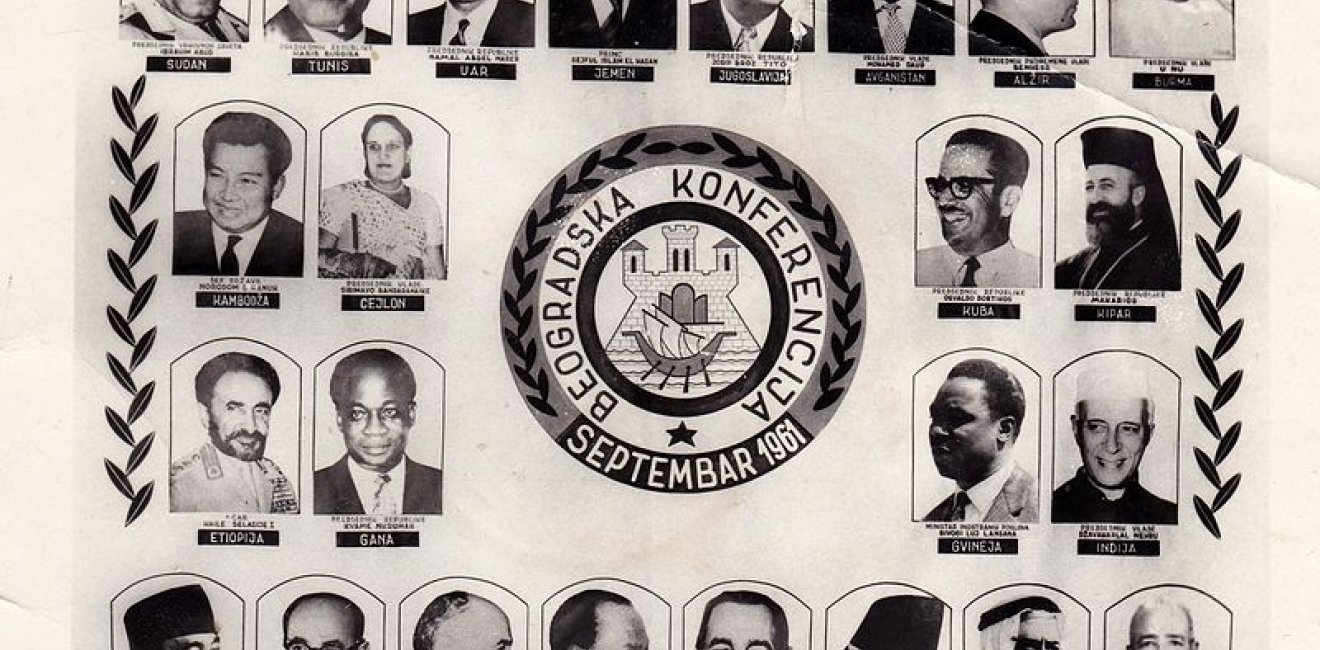

Following the anti-colonial, Afro-Asian, and non-aligned conferences from Brussels in 1927 through Bandung in 1955 to Jakarta in 1992, I analyzed many of the published speeches and resolutions passed at these conferences. The most comprehensive collection for these type of sources being the 12 volume series edited by Odette Jankowitsch, Karl P. Sauvant ,and Jörg Weber, The Third World Without Superpowers, which documents conference speeches along with all declarations and resolutions between 1961 and 1992.

Additionally, my study draws on the archival holdings of the Museum Konferensi Asia Afrika in Bandung, which includes many visual materials such as posters, maps, photographs, and films, and the Arhiv Jugoslavije (AJ)/ Kabinet Predsednika Republike in Belgrade.

Finally, in order to capture the perspective of observers to the NAM, my study integrates material from the Political Archive of Germany’s Federal Foreign Office (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes or PAAA); of the British Foreign Office at the National Archives (TNA) in Kew; of the U.S. State Department at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC; and of the United Nations Archives (UNA) in New York.

These holdings—like the Kabinet Predsednika Republike—include press clippings, minutes, ambassadors’ reports and a whole number of discussion, position and strategy papers on the NAM authored and collected by foreign policy experts, diplomats and ambassadors in Belgrade, Bonn, London, Washington, DC, and New York. Such material gives vivid insights into how the staff of foreign ministries and international organizations sought to make sense of this novel phenomenon in international relations, that confronted them with a crucial provocation.