“Defying Trump, Iran says will boost missile capabilities,” the Reuters headline read. The article, posted on September 22, 2017, went on to describe the military parade held in Tehran earlier that day. Among the soldiers and weapons on display at the exhibition was the Khorramshahr ballistic missile developed for the Aerospace Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC). The missile, Reuters noted, had a range of 2,000 kilometers and was “capable of carrying several warheads.”

So, there you have it. A defiant Iranian show of force staged to flout the authority of the United States and President Trump. A dangerous new missile with a hard-to-pronounce name. Those ubiquitous Revolutionary Guards taking over and militarizing Iran. What more is there to know?

It turns out that nothing about this story can be understood without accounting for the history and context the Reuters report left out.

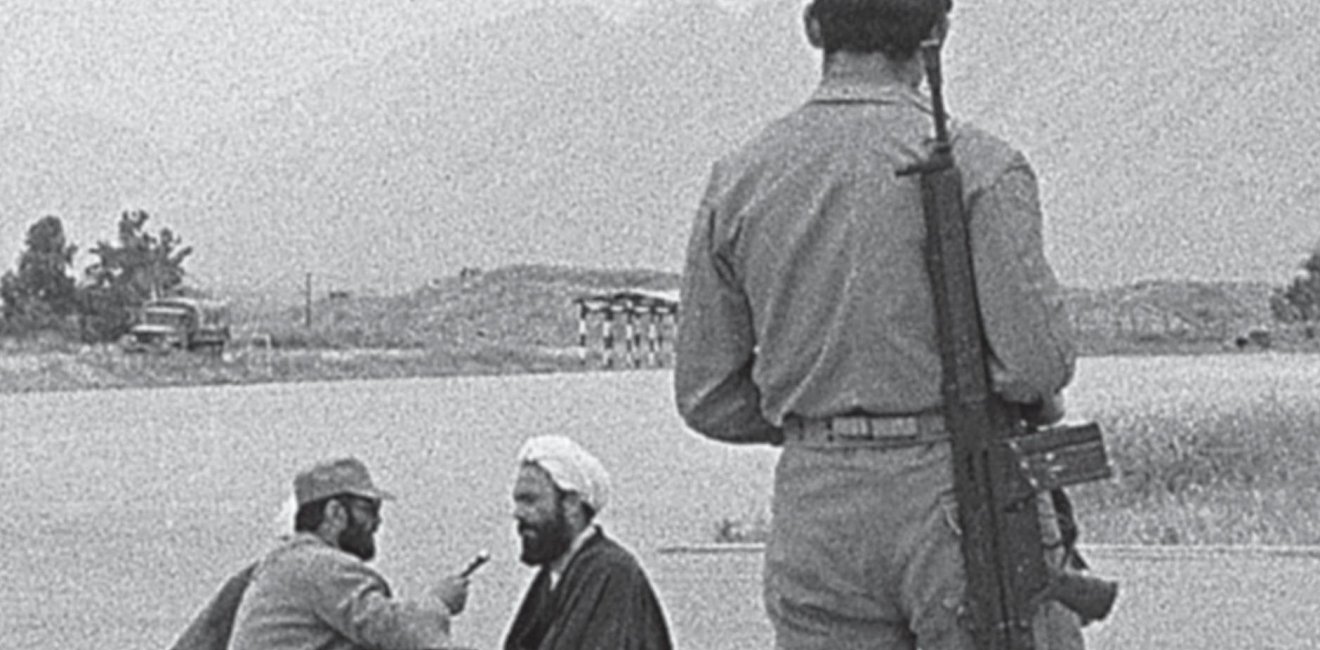

Iran holds a military parade every year on September 22, the date of the Iraqi invasion of Iran in 1980, to mark the beginning of “Holy Defense Week,” the annual commemoration of the Iran-Iraq War. The parade memorializes the country’s resistance against a foreign attack and typically features armed forces marching in formation, tributes to those lost and wounded during the conflict, and the unveiling of new weapons. In their speeches, Iranian leaders address not only the legacies of the war but also contemporary security challenges, as the two are closely and explicitly connected.

And that fact was everywhere on display, yet not for the readers of the Reuters report. While noting the specifications of the new Khorramshahr missile, and that Iran’s development of its missile capabilities represented a “reject[ion]” of US “demands,” the story did not mention that the Khorramshahr missile introduced at a parade commemorating the Iran-Iraq War was named for a city that was captured by Iraqi forces early in that war and that remained under occupation for over a year; or that Iran’s retaking of that city marked the culmination of a months-long campaign to expel the Iraqis; or that it represented a turning point not only in the war but in Iran’s modern history and a declaration of Iran’s determination to defend its independence. As Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said in his speech at the event, “We will increase our military power as a deterrent. We will strengthen our missile capabilities. … We will not seek permission from anyone to defend our country.” Khorramshahr – the city, the battle, the ballistic missile – therefore signifies how the Iran-Iraq War pervades both the form and content of Iran’s security doctrine and how understanding the history of the conflict is essential.

As this incident reveals, however, the Iran-Iraq War is not in fact well-understood outside of Iran, despite its centrality not only to Iran’s security doctrine but also much more broadly. Further, and unfortunately, the Reuters story is but one of many examples of the mischaracterization of Iranian positions and policies that regularly appear in Western media and that gain traction among policymakers and the public. One of the primary reasons for both these mischaracterizations and the failure to fully understand the importance of the Iran-Iraq War can be found in the neglect of Iranian sources and perspectives and the reliance instead on a literalized interpretation of the regime’s rhetoric. Importantly, Iranian voices are very much active and available to researchers and analysts, if we choose to seek them out and listen to what they have to say. And, as the Reuters story and the recent history of U.S.-Iran relations indicate, properly understanding Iran and developing appropriate policies for dealing with the Islamic Republic require that we must.

Indeed, Iranian sources and perspectives challenge many of the prevailing scholarly and popular characterizations of the Islamic Republic, as I discuss in my new book on the IRGC and the Iran-Iraq War. The book’s analysis is based on the massive volume of Persian-language publications on the war produced by top members and units of the IRGC, which provide us with the rare opportunity to go inside the IRGC and to understand Iran’s recent history as the Revolutionary Guards understand it themselves. What we find when we enter upends much of what we thought we knew about the IRGC and the Islamic Republic, in large part because such sources have not been researched or written about by scholars. This oversight can be attributed to several factors. First, much of the existing literature on the Iran-Iraq War was published during or shortly after the conflict and before the vast majority of the IRGC sources became available. Second, there are hardly any traces of the IRGC publications in existing studies, so researchers have little reason to be aware that they exist. Their imperceptibility is compounded by the popular image of the IRGC as an ideological military unlikely to invest in historical scholarship. Finally, all the IRGC sources are in Persian, which many people writing about Iran do not read.

Such shortcomings have too often constrained scholarship and policy-making alike, and have inhibited our understanding of the IRGC, the Iran-Iraq War, and the Islamic Republic as a whole. It’s accordingly incumbent upon scholars and analysts to reject essentialized and sound-bite-driven renderings of Iran, which often promote and are predicated on fear, and to rely instead on critical yet dispassionate analysis of Iranian sources and perspectives.