Vietnam’s Misunderstood Revolution

What both advocates for and critics of the Vietnam War got wrong about North Vietnam: its radical commitment to communist revolution.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

What both advocates for and critics of the Vietnam War got wrong about North Vietnam: its radical commitment to communist revolution.

What both advocates for and critics of the Vietnam War got wrong about North Vietnam: its radical commitment to communist revolution

During the 20th century, anti-Western revolutions swept throughout Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Embracing ideologies from communism to Islamism, these revolutions sought to overthrow or roll back Western domination.

Revolutionary states—whether large like the Soviet Union and China, or small like Cuba and Nicaragua—might have hindered the West, but they were never able to defeat it. Many have collapsed, including the once mighty Soviet Union, and most survivors have made peace with their former Western enemies.

Nevertheless, even small revolutionary states had tremendous impact on world politics in their heydays. This is particularly true of communist North Vietnam, or the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, which at one point provoked the United Stated to commit about half a million troops to defending South Vietnam and to fight a long, bitter, and divisive conflict.

North Vietnam’s war profoundly divided American citizens, seriously damaged American credibility around the world, and lent moral support to many radical movements in Africa and Latin America. Some observers credit the conflict for inspiring “antisystemic movements” in the 1960s and 1970s in North America, Europe, Japan, and Latin America; another source counts at least 14 revolutions that ensued in the seven years following US withdrawal of troops from South Vietnam in 1973.

Revolutionary impact aside, America’s failure at hands of North Vietnam also led to changes in US military strategy and caused the US to retreat from nation-building missions abroad in the subsequent two decades—a self-restraint that was only partially lifted with the Al-Qaeda attacks of September 11, 2001.

Given their limited military and economic capabilities, the ability and determination of small but radical states like North Vietnam to inflict such humiliation on a superpower poses a significant analytical puzzle: What were the thoughts of revolutionary leaders in those states? How could they even consider challenging those much more powerful than they were?

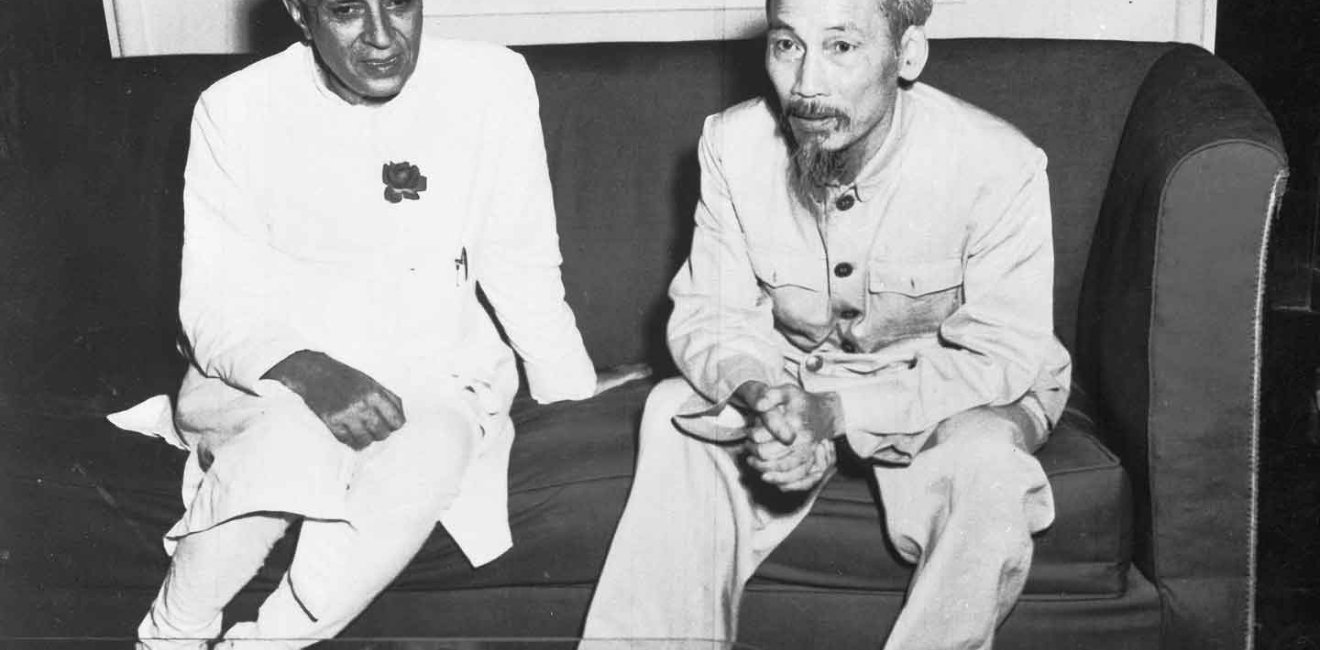

These questions must be asked of all revolutions, but they hold special importance in the Vietnamese case because the nature of this revolution has been widely misunderstood. During the Vietnam War, Vietnamese revolutionaries were commonly portrayed either as dominoes in the game of big powers or as essentially nationalists who inherited a tradition of patriotism and were motivated by national independence—but the North Vietnamese were in fact radicals who dedicated their careers to realizing a communist utopia.

In opposing American intervention in Vietnam, contemporary critics and antiwar activists typically claimed that the Vietnamese revolution was aimed at achieving national self-determination. Vietnamese revolutionaries were said to be reenacting the patriotic tradition of their ancestors through the millennia. Because that tradition had historically been directed against China, Vietnam would not be a menace to the US and could even serve as an American ally to contain Communist China. Senator William Fulbright, an early critic of American policy, stated as much:

Ho Chi Minh is not a mere agent of Communist China…He is a bona fide nationalist revolutionary, the leader of his country’s rebellion against French colonialism. He is also…a dedicated communist but always a Vietnamese communist…For our purposes, the significance of Ho Chi Minh’s nationalism is that it is associated with what Bernard Fall has called “the 2,000-year-old distrust in Vietnam of everything Chinese.” Vietnamese communism is therefore a potential bulwark—perhaps the only potential bulwark—against Chinese domination of Vietnam.

Dr. Martin Luther King, in a famous address in 1967, similarly took issue with the US government for rejecting

a revolutionary [Vietnamese] government seeking self-determination, and a government that had been established not by China (for whom the Vietnamese have no great love) but by clearly indigenous forces that included some communists. For the peasants, this new government meant real land reform, one of the most important needs in their lives.

While Senator Fulbright and Dr. King were correct that the Vietnamese revolutionary government was led by indigenous forces, they underestimated its internationalist commitments to world revolution. While giving priority to their own revolution, Ho Chi Minh and his comrades did not ignore revolutions elsewhere. They supported them in Indochina, Siam, and Malaya in the 1930s, China in the late 1940s, and Laos and Cambodia in 1975. Vietnam continued to train sappers for, and send surplus weapons to, Algeria, Chile, and El Salvador in service of foreign revolutions even after 1975. The internationalist spirit of the Vietnamese Communist Party is still alive today, a quarter century after the collapse of world communism, as evidenced in Party chief Nguyen Phu Trong’s trip across the globe to Cuba in 2012 where he preached the merits of socialism and the evils of capitalism.

Dr. King’s characterization that the Vietnamese had “no great love” for China also misses the awe and veneration Vietnamese communists showered on Chinese leaders in the 1950s and the slavish deference the Vietnamese leadership today expresses toward China. North Vietnamese leaders did implement a “real land reform” by redistributing large amounts of land to landless peasants, but they also executed about 15,000 landlords and rich peasants in the process. For all that bloodshed and fanfare, barely five years later most peasants were coerced into giving up their land and joining Maoist-style cooperatives. Forced to stay in cooperatives, the free farmers of North Vietnam were turned into a kind of serfs or indentured workers. They were chronically hungry and occasionally threatened by famines.

Antiwar activists misunderstood the nature of the Vietnamese revolution, but proponents of intervention fared no better. To justify American involvement in the conflict, US leaders frequently put forward an opposite image of the Vietnamese revolutionaries, claiming they were pawns in the hands of Moscow or Beijing. Portrayed in this manner, the Vietnamese communists did not possess their own beliefs nor were they capable of independent action.

Then-Assistant Secretary of State Dean Rusk testified before a Congressional committee in 1951 that Vietnamese communists were “strongly directed from Moscow and could be counted upon…to tie Indochina into the world communist program.” A decade later, when he sent American troops to Vietnam, President Lyndon Johnson pointed to Beijing as the real culprit:

Over this war—and all of Asia—is another reality: the deepening shadow of Communist China. The rulers in Hanoi are urged on by Peking. This is a regime which has destroyed freedom in Tibet, which has attacked India and has been condemned by the United Nations for aggression in Korea. It is a nation which is helping the forces of violence in almost every continent. The contest in Vietnam is part of a wider pattern of aggressive purposes.

This domino theory justified US intervention in Vietnam. As Senator Hubert Humphrey spoke in 1951, “We cannot afford to see southeast Asia fall prey to the Communist onslaught…If Indochina were lost, it would be as severe a blow as if we were to lose Korea. The loss of Indochina would mean the loss of Malaya, the loss of Burma and Thailand, and ultimately the conquest of all the south and southeast Asiatic area.”

In retrospect, however, it is clear that the Vietnamese communists were no stooges of Moscow or Beijing. At the height of the war, Hanoi’s leaders in fact challenged both their Soviet and Chinese comrades for not daring to stand up against US imperialism. After their victory in 1975, they thought of themselves as the vanguard of world revolution and snubbed not only Washington, but also Moscow and Beijing.

Hanoi attempted to defend the international communist camp even when Moscow and Beijing had abandoned it. In 1989, when Eastern European communist regimes were about to fall, the General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party prodded the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to convene a conference of all communist and workers parties to discuss strategies to save the socialist camp from the coming collapse.[1] When Gorbachev turned a deaf ear to the Vietnamese request, Vietnam asked China to create an anti-imperialist alliance (Beijing also said no).[2]

In the end, Vietnamese communism stopped short of exporting revolution beyond Indochina because its radical character had created enemies everywhere around it, from Vietnamese peasants who resisted collectivization, to China and Cambodia which resented Vietnam’s arrogance. The pro-intervention camp widely exaggerated the security threat of the Vietnamese revolution to the US. That threat did not materialize—not because the Vietnamese communists were not real communists, as the antiwar camp claimed, but because their fanaticism was self-destructive and engineered their own demise.

Both sides in the Vietnam War debate misunderstood the nature of the Vietnamese revolution because they failed to grasp Vietnamese leaders’ profound commitments to communism. As this debate continues today, the same misunderstandings are frequently found in the literature.

[1] Huy Duc, Ben thang cuoc [The winning side], vol. 2 (Osinbook 2012), 63-67.

[2] Tran Quang Co, Hoi uc va suy nghi [Memories and thoughts] (Unpublished, 2003).

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more