Visions of World Order in the "Medina of Muslims": New Avenues for Research on Iran, Afghanistan, and the Legacies of 1979

Historian Timothy Nunan goes beyond the state archives to understand the true legacy of 1979 for Iran and Afghanistan.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Historian Timothy Nunan goes beyond the state archives to understand the true legacy of 1979 for Iran and Afghanistan.

The fortieth anniversary of the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 2019 invites us to reflect on the legacies of 1979 for today. The overthrow of the Shah’s regime and establishment of an Islamic Republic turned Tehran from America’s regional gendarme to one of its most bitter enemies; and American support for the anti-Soviet Afghan jihad turned the Afghan-Pakistan borderlands into a crucible for international jihadism. The opening of Soviet archives since the 1990s has given us a much better sense of Moscow’s intentions in invading and withdrawing from Afghanistan, but with few exceptions, histories of the region’s 1980s written from the inside out—from the point of view of Iranians and Afghans themselves—remain something of a work in progress

Granted, conditions in both countries can make archival research there challenging. A Princeton PhD student researching 19th century Iranian history in the Iranian National Archives was arrested in 2016, and while the National Archives of Afghanistan contain many riches, many files related to the PDPA regime were apparently destroyed in the chaos of Afghanistan’s civil war in the 1990s.

Yet for the historian willing to think beyond just state archives, there are ample opportunities to begin to think about the legacies of 1979 for the region itself. Members of the Afghan Communist regime, such as ‘Abdulwakil, the Foreign Minister from 1986-1992, have written memoirs that provide insight into the workings of the regime in Kabul; while the Islamic Revolution Documentation Center in Tehran has produced hundreds of “memoirs” (in reality, often guided interviews) from members of the Iranian Islamist opposition movement who took on positions within the Islamic Republic following the collapse of the Shah’s regime. The Afghanistan Center at Kabul University has digitized thousands of Afghan periodicals from the anti-Soviet jihad, while in Berlin, the Center for Iranian Oral History has produced hundreds of hours of interviews with members of the Iranian Communist Party and other leftist groups. All of these documents contain obvious silences and elisions. However, read in combination with one another and other sources, they can allow historians to begin to capture the range of transnational actors that transformed the Middle East in the 1980s.

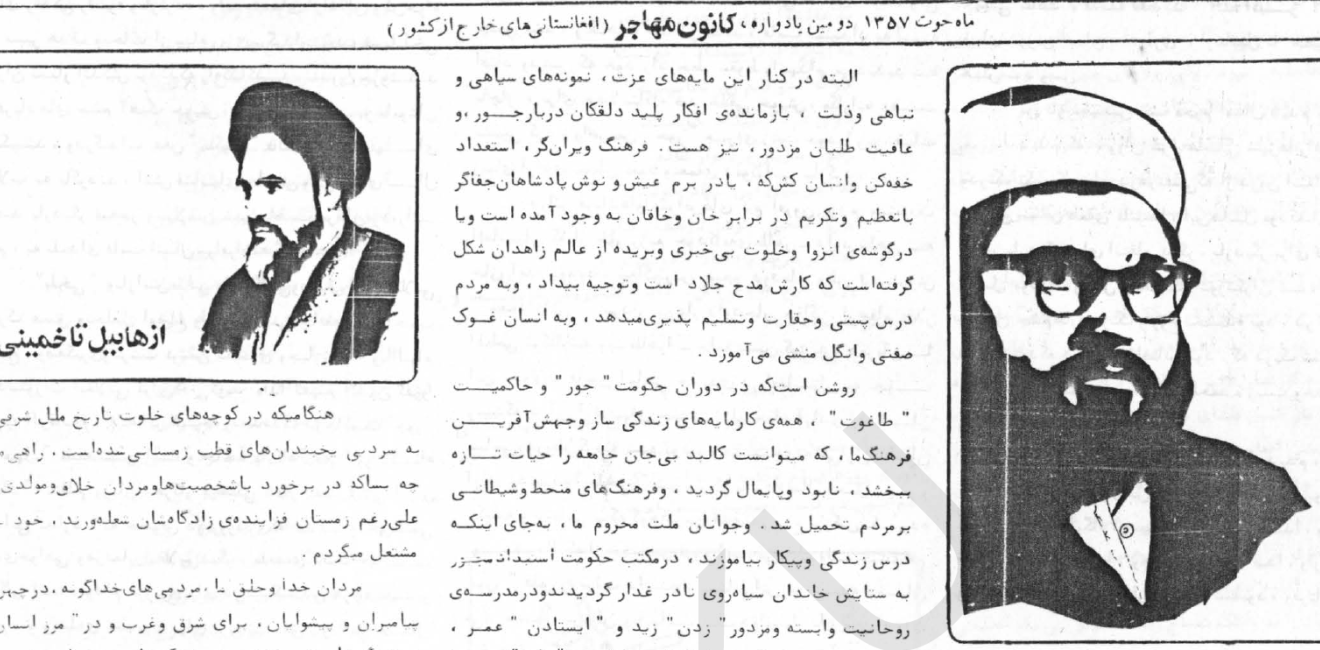

To provide a sense of some of the possibilities out there for scholars of international history, I would like to focus on one recent documentary finds from my work with this eclectic source base, namely the newspaper The Migrant’s Message, a newspaper produced from 1978-1983 by Afghan intellectuals based in the Iranian city of Qom. Even the best narratives of the Soviet-Afghan War in the 1980s focus on decisions made in Moscow and Washington, and when they do focus on Afghans, it is usually mujahidin actors in Pakistan or the Communist regime in Kabul. Yet Afghans were on the move long before the Soviet invasion. Afghan Shi’i scholars and political Islamists traveled to centers of religious scholarship like Qom in Iran and Najaf in Iraq long before the Soviet invasion. As former editors for the newspaper like Sayyid Mohammedreza Alavi explain, the dissolution of Pahlavi regime gave Afghans a free hand to print newspapers that envisioned a cultural revival for their homeland – particularly pressing in light of the Marxist-Leninist regime that had seized power in Afghanistan in April 1978. In late 1978, several Afghans in Qom founded the Migrants’ Chamber for Afghanistanis Abroad (Kānūn-e Mohājer-e Afghānistānīhā-ye Khārej az keshvar), a coordinating body for anti-imperialist Afghan Shi’i living in Qom.

Thanks to the curatorial and digitization work of archivists at the Afghanistan Center of Kabul University, we can see how the authors for the Migrant’s Message engaged with the thought of Ayatollah Khomeini, the late Afghan poet Sayyid Ismail Balkhi, and the late Iranian intellectual ‘Ali Shariati. For me, however, one recent intriguing theme in the magazine has been its engagement of other Islamic and national liberation movements. Until the death of the Iranian Islamist internationalist Mohammed Montazeri in 1981, groups like the Chamber of Migrants possessed a certain freedom to use the Islamic Republic as a platform for their causes.

The diverse social world of what one Turkish Islamist called the “Medina of Muslims” (i.e. revolutionary Tehran) found expression in the pages of The Migrant’s Message. Banners at the bottom of the newspaper’s page proclaimed solidarity with Palestine, Eritrea, and the Phillippines. Afghans—at least these Afghans—were internationalists, and they saw their struggle against Soviet imperialism as entwined with those against the Israeli occupation of Palestine, Ethiopian domination of Eritrea, or the lack of self-determination for the Moro people. Even more intruiging were a series of poems from other liberation movements in Tehran that the magazine had translated into Persian. One poem from the Polisario movement in the Western Sahara, went as follows (appearing in Persian, with my rough English translation):

می توانی شکنجه بدهی

می توانی دست راست، و دست چپ مرا قطع کنی

می توانی پاهایم را با ارههای ساخت آمریکائی ات از تن جدا کنی

می توانی شکمم را با کارد سلاخی اهدائی اسرائیل پاره کنی

می توانی قلب را از درون سینه ام بیرون آوری

و در میان چنگالهایت بفشاری

و، می توانی زبانم را قطع کنی …

اما، قلب من در دست تو دژخیم! خواهد گفت:

مرگ بر استعمار

مرگ بر امپریالیسم آمریکایی حامی استعمار

و فریاد خواهد زد:

زنده باد آزادی

You can torture me

You can cut off my right hand and my left hand

You can separate my legs from my body with your American saw

You can tear apart my gut with an Israeli butcher knife

You can remove my heart from my chest

And crush it under your pitchforks

And you can cut out my tongue

And yet my heart, in your hand, you hangman, will say:

Death to colonialism

Death to American imperialism, the patron of colonialism

And it will scream: long live freedom.

Analysis of poetry may not be in the toolkit of every diplomatic historian, but a few themes emerge even from this short poem from Sahrawi liberation fighters. This poem, like the others, had little to do with visions of Islamic liberation per se, reminding us of how fluid boundaries between “Islamist” actors like the Afghans and “secular” actors like the Sahrawis were. Many contributions to The Migrant’s Message focused on thinkers with perhaps a limited resonance to non-Shi’i, but at least in the early 1980s, they were keen to emphasize to their readership (Afghans in Iran and, to a lesser extent, Iranians interested in the Afghan cause) how the Afghan struggle fit into global networks of solidarity. The poem shows an awareness of how American and Israeli expertise and technologies of torture circulated among independent post-colonial states, even those in the Muslim or Arab world. And it shows how subnational political actors in Tehran—the Sahrawi revolutionaries behind Polisario or Afghan Shi’i Islamists–adapted Iranian slogans like “Death to America” for their own causes. Afghan Shi’i Islamists would use the slogan “Death to Global Imperialism Led by America, Russia, and China” throughout the 1980s, for example.

This is just one poem from one issue of The Migrant’s Message, but readers of Persian are invited to consult the other poems from Dhofar, Palestine, and Algeria here, or a longer poem written by Afghans on Latin America from a later issue here.

Sources like The Migrant’s Message have much to offer to scholars of international history. For those interested in the Soviet-Afghan War, they remind us of how the conflict involved Shi’i Afghan actors based in locations like Quetta, Mashhad, Tehran, or Qom not often adequately studied in treatments of that conflict. They also remind us of how Afghans were not just fighters but also intellectuals, interested in poetry and international affairs. Indeed, one theme that emerges from studying these Shi’i Afghan sources is their deep regret about the way in which the Soviet intervention and subsequent American/Saudi/Pakistani aid to the Afghan resistance militarized what had been a non-violent struggle for cultural hegemony.

For scholars of the Cold War, they remind us of how actors beyond the superpowers sought to appropriate that conflict for their own ends. Some scholars of American foreign relations have been overeager to reduce twentieth century international history to a tale of American ascendency. But not only the Soviet Union, but also less powerful actors like China, India, or the Afghan resistance had their own ideas about international order that were not reducible to anti-Americanism. Incorporating voices like those of these Afghans is essential therefore not just for historians of Afghanistan or Islamism, but also international history writ large.

Finally, the voices of Islamist actors have much to add to the conversation about anti-colonial internationalism. Recent scholarship has reexamined the role of projects like the New International Economic Order that attempted to create a “welfare world” of states, only to crash upon the rocks of neoliberalism. Yet Islamists were also internationalists, and they sought to redeem what they viewed as an illegitimate international system well into the 1980s. Not only did Tehran sponsor liberation movements seeking to overthrow existing regimes (like in Afghanistan) or carve out their own states (like in Western Sahara); its message also resonated with intellectuals critical of how the new politics of international debt and structural adjustment made it impossible for peoples to rise up against imperialism, whether in Turkey or Poland.

Future research on Islamist internationalism might contribute to all of these conversations, helping us to reconstruct the contested legacies of 1979. A rich set of sources is out there, waiting to be engaged by scholars willing to learn languages like Persian, Arabic, Urdu, or Pashto.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more