What Defines An Archive? Ask a Jewel Thief

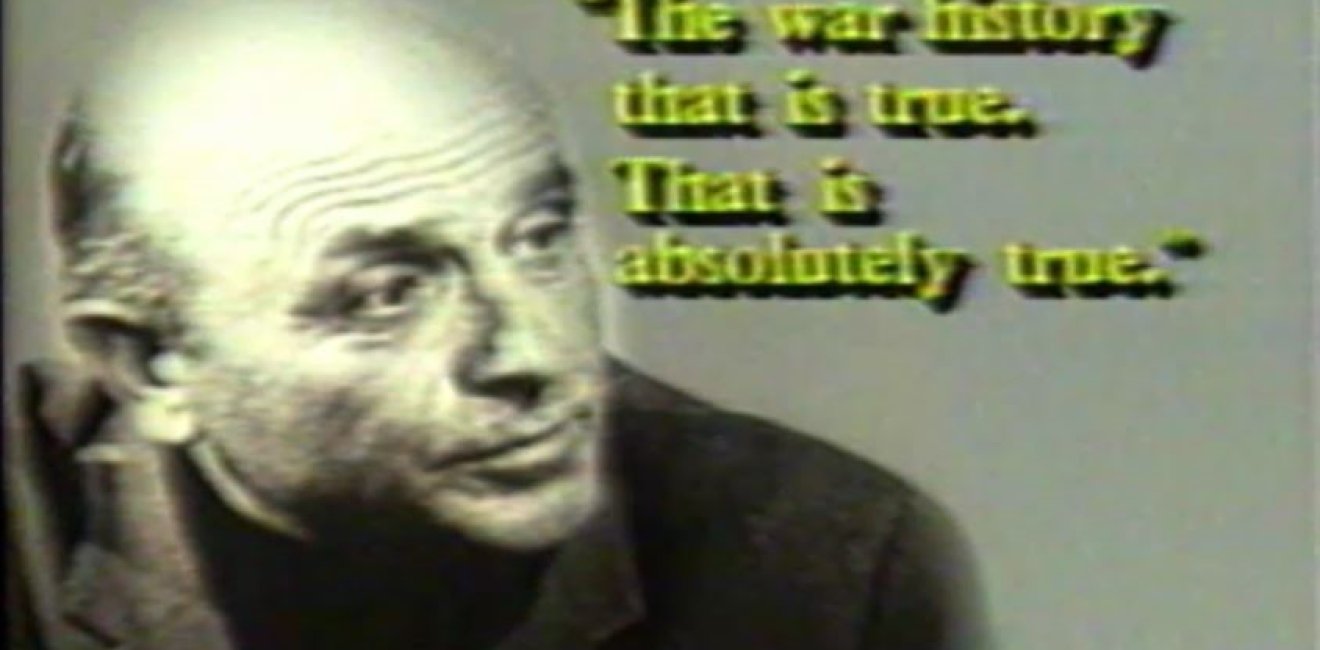

Klaus Barbie, World War II Gestapo Chief in Lyon, France, admitted wartime atrocities in audio tapes uncovered by ABC News after his arrest in 1983.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Klaus Barbie, World War II Gestapo Chief in Lyon, France, admitted wartime atrocities in audio tapes uncovered by ABC News after his arrest in 1983.

Klaus Barbie, World War II Gestapo Chief in Lyon, France, admitted wartime atrocities in audio tapes uncovered by ABC News after his arrest in 1983.

Thirty-four years ago this month, on August 16, 1983, the United States Government issued a formal apology to the government and people of France. It came with a shocking admission.

Early in the Cold War, the Justice Department revealed, US Army officers secretly helped Klaus Barbie, a notorious Nazi war criminal, avoid French prosecutors and flee to South America, escaping trial in the torture and murder of 4,000 French Jews and Resistance fighters in Lyon.

American complicity in Barbie’s 1951 escape came to light 33 years later thanks partly to documents, photographs, and recordings stored in archive-style caches, some conventional and some highly improbable.

As it happened, the US Government’s Barbie investigation nearly never happened. “We are not the department of history,” said Attorney General William French Smith, resisting calls for action by nine members of Congress.

The stir on Capitol Hill came after a report on the ABC Evening News of February 11, 1983, exposing evidence of American assistance in Barbie’s escape.

As a correspondent acting on a tip, I had flown from New York City to western Canada. Sitting in a cramped living room in Vancouver, I listened to Robert Wilson, an admitted international jewel thief, play audio tapes of conversations he recorded with Barbie in 1975 in preparation to write a book.

Wilson’s files included a collection of photos that showed the two fugitives had become close friends in Bolivia, where Wilson, too, had taken refuge.

“I have a criminal background, of some 30 years,” Wilson told me, “and he’s [Klaus Barbie] obviously a very cultivated criminal. We felt very comfortable around each other.”

Wilson’s interview and papers suggested strongly that Barbie was, indeed, a war criminal (“Butcher of Lyon”) hired at war’s end, perhaps unwittingly, by U.S. Army agents to run a spy ring in East Germany. Then, in 1951, to avoid embarrassment, they helped him escape through Italy.

“The war history, that is true; that is absolutely true,” said the voice identified as Barbie’s. “I go to kill…to Lyon. I have been ordered to fight the Resistance. And these orders have been very strict, to kill.”

Had Barbie said he escaped with help from the Americans?

WILSON: “They became very friendly and according to him he struck a deal with them.”

MARTIN: “Did he ever tell you he had continuing contacts with the American intelligence…”

WILSON: “Oh, he told me that on a number of occasions, yes.”

MARTIN: “What did he say about that?

WILSON: “Well, he just used the term, ‘I’m on very good relationships with the Americans’ and have been; he mentioned the fact he’d been in New Orleans; he loved San Francisco.”

Barbie was captured and returned to France in early February 1983. My tip and story came several days later. Nevertheless, the Justice Department still balked at looking into what it saw as a mere question of “history.”

That’s when a second archive came into play. At the suggestion of a sympathetic agent of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (now Homeland Security), I requested a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) search of INS visitor entry-exit forms filed by Barbie or a Bolivian businessman named Klaus Altman (Barbie’s alias).

Within days, the results turned up at my office in New York. When I told the Justice Department that ABC News was about to broadcast images of documents that all but proved Barbie had visited the United States, the Attorney General changed his mind and ordered an investigation.

Over the next several months, as US government investigators peered into conventional archives at the CIA, Pentagon, State, and Justice Departments, I found traces of Barbie through documents and photos stashed in less conventional places.

The first set of papers should have existed in La Paz at the Bolivian Interior Ministry. But when I arrived, Barbie’s files were empty, ransacked, the staff said, by officials of the previous regime whose leaders had protected Barbie for many years.

Here I struck out. But help was on the way.

Thanks to another tip, a batch of papers was offered to me on a sidewalk in La Paz. They were photostats of Barbie’s 1951 travel documents issued in Rome.

The young man who was offering to sell them to me for $3,000 said he had bought them a decade earlier and wanted only to recover his investment. He accepted $300.

This “street archivist” had been sent to me by Allan Ryan, the Justice Department’s Special Investigator who had flown to La Paz to gather information. He said department finances (and a sense of caution) prevented him from buying them himself.

When I showed him the papers, his reaction was immediate:

“I quickly saw that they were originals,” Ryan wrote later in a memoir, “extremely important to the case, and obtainable nowhere else.”

One page showed Barbie had used an Allied High Commission passport to reach Italy under a false name. His Bolivian visa listed his sponsors as a Catholic priest in Rome and a Franciscan leader in Bolivia. He claimed assets of 850 dollars.

In a typewritten 1973 affidavit, Barbie denied that he used an alias to become a Bolivian citizen or that he worked for American intelligence in Germany.

As I sifted these papers, I saw Barbie shedding an old identity and escaping Europe with the help of American army officials desperate to avoid blame for their dubious decision to employ someone who turned out to be a heinous war criminal.

Yet, as far as I could tell, nothing directly connected Barbie to the CIA in South America, which was the persistent and tantalizing rumor that had brought us all to Bolivia.

Still another cache of documents arrived from a Bolivian lawyer who had served Barbie prior to his capture and expulsion to France. For reasons not clear to me, he held dozens of the fugitive’s personal photos, including images not even seen by his jewel thief friend Robert Wilson, who introduced us.

I paid the lawyer a few hundred dollars and we videotaped them all, creating a vast collection placed in ABC News warehouse in New Jersey. For all I know they are still there.

The final trove of documents rested in Langley, Virginia, at the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters. In March, 1983, ABC News filed a lawsuit to restore the ocean of words blacked-out by out by the CIA on documents mailed us under our FOIA request.

In early August, trying to persuade us to drop our lawsuit, the agency offered us an unusual compromise: If we agreed to withdraw our suit, CIA archivists would allow us to visit a room at their headquarters where they would bring the documents and answer our questions – but not display them.

It turned out to be a farce, a kind of verbal pin-the-tail on the donkey. Metaphorically blindfolded, I stumbled around for a couple of hours before surrendering and leaving.

Days later, Ryan stood at a microphone in the Justice Department to announce his findings.

US Army officers had obstructed justice three decades earlier, he explained calmly, but there would be no punishment because the statute of limitations had run out.

Then he delivered a note of grace for the United States government, explaining its decision to make a formal apology to the French.

“Justice delayed is justice denied,” he said, echoing the 19th Century English jurist William Gladstone. “If we are to be true to that principle and we ought to be true to it, we cannot pretend that it applies only within our borders and nowhere else,” Ryan said, “We have delayed justice in Lyon.”

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more