A collection of documents from the Central Archive of the Russian Ministry of Defense (TsAMO), available in English for the first time on the Wilson Center Digital Archive, offers fascinating new details of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

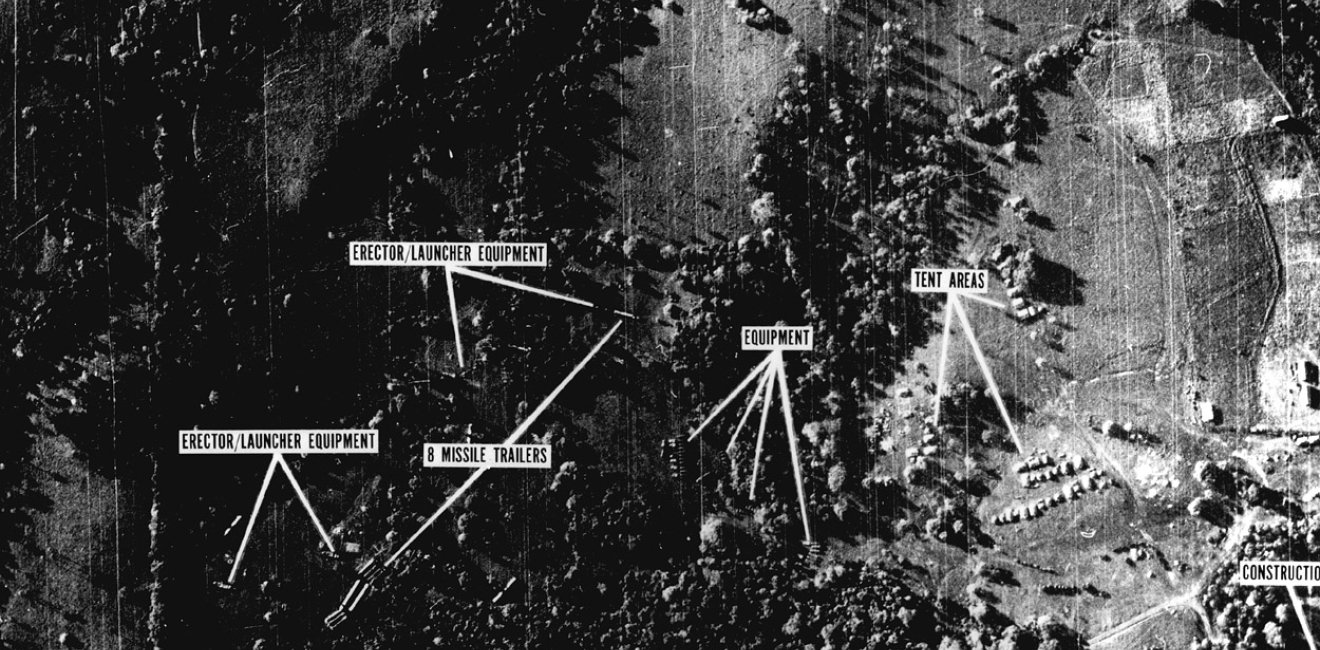

The collection consists of over 30 formerly top-secret documents from the spring, summer, and fall of 1962. Joining an already large body of archival records on the Cuban Missile Crisis (over 600 documents, as of writing), these new sources provide exceptional insights into Soviet military planning during the secret “Anadyr” operation (the deployment of Soviet ballistic missiles and troops to Cuba), including information regarding the personal conduct of Soviet troops stationed in Cuba, instructions for interactions with foreign vessels, and the composition of troops.

The documents were declassified by the Russian Ministry of Defense in May 2022, a somewhat surprising decision given Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine and the deteriorating political situation within Russia.

Many of the documents have already been put to good historical use by Cold War scholars. Sergey Radchenko and Vladislav Zubok relied on these documents for a recent article in Foreign Affairs titled “Blundering on the Brink: The Secret and Untold History of the Cuban Missile Crisis.” Radchenko and Zubok make clear that the Soviet intervention in Cuba was not the meticulous plan that Khrushchev made it out to be, but rather “a remarkably poorly thought-through gamble whose success depended on improbably good luck.”

The new materials on the Wilson Center Digital Archive gives credence to Radchenko and Zubok’s claim, as evidence of Soviet ineptness abounds throughout the collection.

The lack of even modest expertise on Cuba among the Soviet military leadership stands out as a flagrant example of Soviet failings. Documents from the collection reveal that Soviet troops arrived in Cuba severely underprepared, apparently not realizing that the island’s tropical climate would wreak havoc on their weapons and equipment. Fuse failures, excessive corrosion, overconsumption of oil, and generator blackouts were just some of the complaints made by troops on the ground. Recommendations as to how to counter the effects of a warm climate and requests for new equipment were made throughout the spring and summer of 1962, but no action was taken by Moscow until August.

Other findings from the collection are probably less significant when it comes to analyzing the USSR’s strategic blunders, but still offer interesting details into the “Anadyr” operation. One memorable report describes the cigarette rations for secretly deployed Soviet troops – 25 a day – and the fact that servicemen were prohibited from visiting any place of entertainment in Cuba or taking walks for pleasure. All aspects of the mission, no matter how big or small, were “performed in strict secrecy under the pretense of the cover stories.”

Visits to cultural and education institutions, such as theatres and museums, were, on the other hand, “limitedly” permitted, as long as all Soviet troops proved themselves to be “models of Soviet socialist ideology” when interacting with Cuban citizens.

The new documents also include a report submitted to Khrushchev by R. Malinovsky on the October 27 shootdown of a U-2 aircraft piloted by American pilot Rudolf Anderson; reports on other close-calls between US and Soviet ships and aircraft; and the rescinding of the “increased combat readiness” status for the Soviet fleet following the resolution of the crisis.

In “Blundering on the Brink,” Radchenko and Zubok are careful to highlight the present-day importance of these Soviet-era documents. Drawing parallels between the hubris that drove the Cuban Missile Crisis and that hubris is driving Russia’s war in Ukraine today, Radchenko and Zubok note that the documents offer potential lessons to keep us safe during a time of pronounced nuclear saber-rattling. Realizing that he was without a winning hand, Khrushchev walked back from the brink, capitulated, and withdrew Soviet missiles from Cuba. It remains to be seen if Putin will also be able to know when enough is enough in Ukraine; if he will then have the capacity to stand down is another question entirely.

Click here to view new documents on the Cuban Missile Crisis from the Central Archive of the Russian Ministry of Defense (TsAMO).