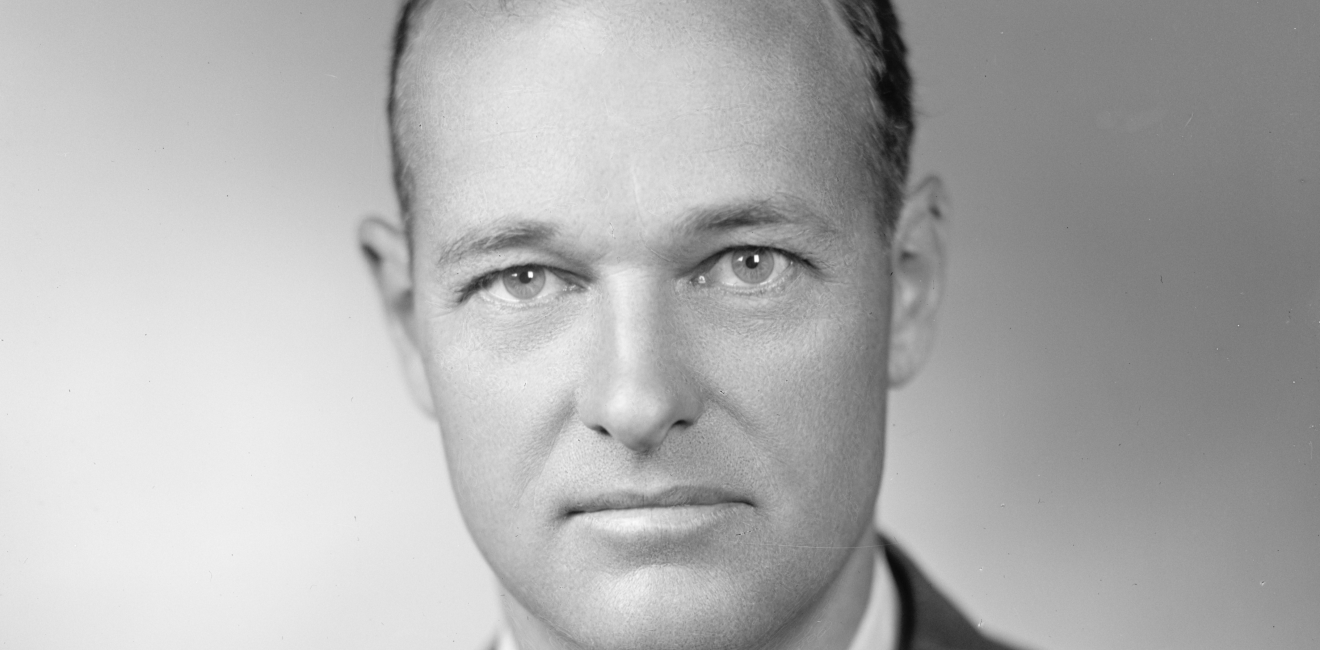

George Kennan is the acknowledged “father” of the Free Europe Committee (FEC), the public-private partnership of the US government and influential Americans that sponsored Radio Free Europe (RFE), distribution in Sovietized Eastern Europe of leaflets and forbidden Western books, and support of East European exiles. Kennan took full credit for his role, writing to FEC Chairman Joseph Grew in November 1954 that “the initial impulse to this undertaking came from myself.” [1] He also played a key role in the establishment of the American Committee for Liberation (AMCOMLIB) and its Radio Liberation/ Radio Liberty (RL) and émigré projects focused on the Soviet Union.

Both projects operationalized Kennan’s conception of political warfare as an offensive element of containment doctrine that he outlined in lectures at the National War College in 1947 and in State Department Policy Planning papers in 1948-1949.[2] Containment included, for Kennan, the “adroit and vigilant application of counterforce” short of military action against the Soviet Union, including exploitation of Soviet vulnerabilities in Eastern Europe – an issue he had identified in 1945 and later regretted not including in his July 1947 “X” article in Foreign Affairs.[3]

Kennan was principal drafter of National Security Directive 4/A of December 1947, which authorized the newly-established Central Intelligence Agency to conduct “covert psychological operations designed to counteract Soviet and Soviet-inspired activities which constitute a threat to world peace and security.”[4] He asked the CIA in early 1948 to recommend whether the mass of refugees from the USSR and Eastern Europe “can be effectively utilized to further U.S. interests in the current struggle with the U.S.S.R.”[5] In May 1948 he submitted to the NSC a paper titled “The Inauguration of Organized Political Warfare” that proposed support of émigré liberation committees, underground activities behind the Iron Curtain, and indigenous anticommunist forces in threatened countries of the Free World. To that end he proposed formation of a public American organization, working closely with government, “enabling selected refugee leaders to keep alive as public figures with access to printing presses and microphones [but] not engage in underground activities.”[6] That paper provided the rational and language for National Security Directive 10/2 of June 1948, which endorsed covert anti-Communist projects, including “assistance to refugee liberation groups,” “propaganda,” and “subversion against hostile states.”[7]

The Office of Policy Coordination, established by NSC 10/2, converted Kennan’s concept into a proposal for a “New York Committee” to support with unacknowledged U.S. government funding a variety of exile activities. An initial focus on Eastern Europe was motivated in part by Kennan’s effort to support East European exiles through an organization separate from the State Department. He wrote later:

The Department of State was beginning to be troubled, by 1949, with frequent visits from various well-known and worthy individuals who were refugees or voluntary exiles from the iron curtain countries. What these people wanted…was mostly sympathy, understanding, and support for their efforts…[to ignite] the spark of hope for a better future in their respective countries. All this they deserved…but it seemed clear to me that the Department of State was not the proper place for them to receive it.…I did not think it proper that geographic desk officers, in particular, who were charged with the responsibility of communication with the official representatives of those governments, should also be entertaining relations with people interested only in the overthrow of the regime in question.[8]

Kennan (along with OPC head Frank Wisner and State Department Soviet expert Llewellyn E. Thompson, Jr.) recommended the OPC plan to Secretary of State Acheson on February 21, 1949. Kennan said it was of “vital importance” and “one of the principal instrumentalities for accomplishing a number of our most important policy objectives.”[9] OPC rented office space in New York and arranged for covert funding, while Kennan joined Wisner in reaching out to attract prominent Americans outside government to the endeavor. Although Kennan failed to enlist Henry Stimson (former Secretary of War) as FEC chairman, he persuaded Joseph C. Grew (former undersecretary of state, ambassador to Japan, and an officer in the U.S. Embassy to Tsarist Russia) to take the position. De-Witt C. Poole (who headed the State Department’s Russia Division in the early 1920s and was later chief of the OSS Foreign Nationalities Branch) agreed to serve as FEC president. Other eminent Americans including Dwight D. Eisenhower and Lucius D. Clay agreed to join the Committee.[10]

The FEC was launched with fanfare on June 1, 1949, with three proclaimed objectives: “to find suitable occupations for those democratic exiles who have come to us from Eastern Europe”; “to put the voices of these exiled leaders on the air, addressed to their own peoples back in Europe, in their own languages, in the familiar tones [and] to get their messages back by the printed word”; and to experience democracy in action in the U.S. and convey that message to their homelands.[11] At Kennan’s request, Secretary of State Acheson informed State Department missions abroad of State’s “unofficial approval” and publicly endorsed the project at a June 23, 1949 press conference: “Yes, the State Department is very happy to see the formation of this group, such a distinguished group. It thinks that the purpose of the organization is excellent and is glad to welcome its entrance into this field and gives it its hearty endorsement.”[12]

With the FEC launched in mid-1949 and focused on Eastern Europe, Kennan, along with Wisner and other State Department and OPC officials, returned to the question of Soviet refugees in Western Europe. Their discussions were informed by a May 1949 OPC paper, “Utilization of Russian Political Refugees in Germany and Austria,” by Robert F. Kelley, a former senior Foreign Service Soviet expert who had mentored Kennan in the 1930s. A Soviet émigré project was defined at a July 1949 State Department–OPC meeting that included Kennan, Wisner, Thompson, and State Department Soviet expert Charles E. Bohlen and authorized in a memorandum to Wisner from Kennan in September 1949; the focus was on émigré welfare until an effective political warfare operation could be organized.[13] A survey of Soviet exiles in Western Europe by Kelley served as the basis for further discussion among Kennan, Wisner, and their associates during the summer of 1950. Following OPC approval on September 28, 1950, AMCOMLIB was launched in February 1951 with the aim “to encourage the establishment in Western Germany by the refugees from every part of the Soviet Union of a central organization embracing all democratic elements.”[14]

Just as for the FEC, George Kennan helped recruit the initial trustees (as AMCOMLIB directors were called), whose roster would include Eugene Lyons (former Moscow correspondent and Reader’s Digest editor, who became AMCOMLIB president); Reginald T. Townsend, who became executive director; William Henry Chamberlin (writer for Wall Street Journal and New Leader and author of a history of the Russian Revolution), Allen Grover (vice president of Time), William Y. Elliot of Harvard, William L. White (journalist and publisher), Charles Edison (former governor of New Jersey), and the Russian-born journalist and author Isaac Don Levine.

Kennan’s interest in Soviet émigré projects was personal as well as professional. Some of the impetus came from knowledge of the “Committee of American Friends of Russian Freedom” established by his great uncle and namesake in the late 1800s.[15] AMCOMLIB efforts in 1952 were devoted not to starting radio broadcasts but to attempting to unify the Soviet emigration. This was seen as the priority by all who were involved in the project—including Kennan, who had left the State Department for Princeton but who was consulted regularly by OPC and CIA officers. But by then Kennan’s interest had shifted to support of Soviet émigrés in the United States through the Committee for the Promotion of Advanced Slavic Cultural Studies and the Free Russia Fund/East European Fund.[16] By the time RL began broadcasting in March 1953, Kennan had given up hope of uniting the Russian emigration (let alone the all-Soviet emigration) and in consequence downplayed the importance of broadcasts to the Soviet Union, which he thought could be conducted by RFE and might serve a later purpose as a bargaining chip with Moscow.

Critic of Covert Action (but not FEC and AMCOMLIB)

In the 1970s and 1980s, after extensive CIA covert activities around the world were publicized, Kennan disavowed much of his earlier advocacy of covert operations by the US government. Yet his reappraisal was more nuanced than is often assumed. As Pricilla Roberts has written in her biography of Kennan’s friend Frank Altschul, “Kennan’s subsequent reflections on the variegated fruits of his advocacy of covert operations would indeed be mixed.”[17] Writing in Foreign Affairs in 1985, he described how, faced with the Soviet threat in Western Europe and elsewhere,

“Our government felt itself justified in setting up facilities for clandestine defensive operations of its own… As one of those who, at the time, favored the decision to set up such facilities, I regret today, in light of the experience of the intervening years, that the decision was taken. Operations of this nature are not in character for this country. Excessive secrecy, duplicity and clandestine skullduggery are simply not our dish … because such operations conflict with our own traditional standards and compromise our diplomacy in other areas.[18]

In this 1985 article, Kennan made a blanket criticism of “secret operations,” but earlier he had drawn a distinction between clandestine para-military operations and secret American funding of political or psychological warfare ventures. Writing to Michael Josselson of the Congress for Cultural Freedom in the late 1960s, after press reports had exposed that much of its funding originated in the CIA, Kennan described “[t]he flap about CIA money” as “quite unwarranted,” telling his correspondent: “I never felt the slightest pangs of conscience about it.…This country has no ministry of culture, and the CIA was obliged to do what it could to fill the gap. It should be praised for having done so, not criticized.”[19] Testifying to the Church Committee of the US Congress in 1975, he explained his advocacy of covert operations as resulting from fears of Russian influence in Western Europe but lamented that: “The political warfare initiative was the greatest mistake I ever made. It did not work out at all the way I had conceived it or others of my associates in the Department of State. …..”[20]

While we lack specific references by Kennan to the Committes and their Radios in his reappraisal of political warfare during these years, there is no indication that he regretted his role in their founding. He remained in touch with his former mentor Robert Kelley, by then an AMCOMLIB executive, who hosted him in a private visit to Radio Liberty in Munich.[21] Looking back in 1989 at the founding of FEC, Kennan wrote in a private letter:

I feel that much injustice has been done in sections of American opinion to those of you who took upon yourselves this difficult and often thankless task [...] suppose the [Free Europe] Committee had never been set up at all (as we must suppose many of its critics would have liked). What would have been the results? Would there not have been, on the part of these refugees, a general sense of coldness, indifference and abandonment at the hands of American society? And would that not have been exploited by the Stalinist forces then predominant in the Soviet Union and in other countries? Obviously, those of you who addressed yourselves to the task of helping these people found yourselves up against the reflection of all the unsolved national and ethnic problems of eastern Europe. But did not your efforts teach many people to put these frictions into better perspective and to recognize the importance of trying to overcome them by the means of mutual understanding and compromise? And did not some of this communicate itself, at least in some degree, back into the homelands?[22]

[1] FEC Letter to Joseph C. Grew from George Kennan, November 4, 1954. FEC and AMCOMLIB corporate records are included In the RFE/RL Corporate Collection, Hoover Library and Archives.

[2] This discussion of Kennan’s role in the founding of the FEC and AMCOMLIB is condensed from my book Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty: The CIA Years and Beyond (Woodrow Wilson Center and Stanford University Press, 2010), Chapter One. Key declassified US government documents are available in Wilson Center Cold War International History Project Digital Archive E-Dossier 32, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

[3] Measures Short of War: The George F. Kennan Lectures at the National War College, 1946–1947 (National Defense University Press, 1991); George F. Kennan, Memoirs. 1925–1950 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1969), 357; Kennan, “Russia’s International Position at the Close of the War with Germany,” May 1945, reprinted in ibid, 532–46.

[4] “NSC 4A, December 17, 1947,” reproduced by Michael Warner, ed., CIA Cold War Records: The CIA under Harry Truman (Washington, D.C.: Center for the Study of Intelligence, 1994), 173–75.

[5] Policy Planning Staff paper 22/1, “Utilization of Refugees from the Soviet Union in U.S. National Interest,” March 11, 1948, in The Department of State Policy Planning Papers 1948 (New York: Garland, 1983), vol. II, 88–102.

[6] “Policy Planning Staff Memorandum,” May 4, 1948, document 269, in U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, various years), 1945–50, The Emergence of the Intelligence Establishment. The final draft of this memorandum, dated April 30, 1948, was released under the Freedom of Information Act with fewer redactions to Douglas Selvage, who kindly made a copy available to the author.

[7] NSC 10/2, June 18, 1948, copy reproduced by Warner, CIA Cold War Records, 213–16.

[8] FEC Letter to Joseph C. Grew from George Kennan, November 4, 1954.

[9] OPC memorandum to Wisner, “Notes on Discussion of New York Committee with Mr. George Kennan, February 18, 1949,” The memorandum is signed by Kennan, Wisner, and Thompson.

[10] Kennan to Bohlen, April 18, 1949, Records of Charles E. Bohlen, box 1, record group 59, NARA, as cited by Michael Wala, The Council on Foreign Relations and American Foreign Policy in the Early Cold War (Providence: Bergham Books, 1994), 215.

[11] FEC memorandum, “Portions of Introductory Statement by Joseph C. Grew”, June 1, 1949.

[12] Department of State airgram, June 21, 1949, excerpt in RFE/RL Corporate Collection; press conference of Secretary of State Dean Acheson, June 23, 1949, American Foreign Service Journal, September 1949.

[13] Department of State memorandum to Wisner from Kennan, September 13, 1949.

[14] AMCOMLIB press release, March 7, 1951.

[15] OPC memorandum, “Cinderella Discussion with Mr. Kennan of 21 August 1950,”August 21, 1950; Kennan interview with Robert T. Holt, Radio Free Europe (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1958), 233.

[16] Pricilla Roberts, Frank Altschul, 1887-1981: A Political and Intellectual Biography , chapter 11, 163-167.

[17] Roberts, Frank Altschul, 1887-1981: A Political and Intellectual Biography chapter 11, 7. This section draws on Roberts’ discussion.

[18] George Kennan, “Morality and Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs 64 (Winter 1985-1986), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/1985-12-01/morality-and-foreign-policy

[19] As quoted in Scott Lucas, Freedom’s War; the American Crusade against the Soviet Union (New York University Press, 1999), 69, as cited in Roberts, op. cit.

[20] As quoted in Peter Grosse, Operation Rollback: America’s Secret War behind the Iron Curtain (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 98-99 and Stephen E. Ambrose, Ike’s Spies: Eisenhower and the Espionage Establishment (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981), 167, as cited by Roberts, op. cit.

[21]Communication from James Critchlow (RL Munich executive) to the author, March 5, 2009.

[22] George F. Kennan to J. F. Leich, September 19, 1989, Private Papers of John Foster Leich, as obtained by Anna Mazurkiewicz and quoted in her forthcoming book Voice of the Silenced Peoples in the Global Cold War: The Assembly of Captive European Nations in the American Political Warfare, 1954-1972. Leich, assistant director of the FEC’s Exile Relations Division in the 1950s, had asked Kennan for comments on a draft article, subsequently published as John Foster Leich, “Great Expectations: The National Councils in Exile, 1950–1960,” Polish Review 35, nos. 3–4 (1990).