Lions, Paper Tigers, and Ghosts: Conversations with Mao from "Long Live Mao Zedong Thought"

Shelley Zhou introduces 58 new additions to the Digital Archive collection, "Conversations with Mao Zedong."

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Shelley Zhou introduces 58 new additions to the Digital Archive collection, "Conversations with Mao Zedong."

What do “tigers” and “ghosts” have in common with each other?

Fifty-eight new Chinese-language documents that have just been published in the Conversations with Mao Zedong collection on the Chinese Foreign Policy Database suggest a connection.

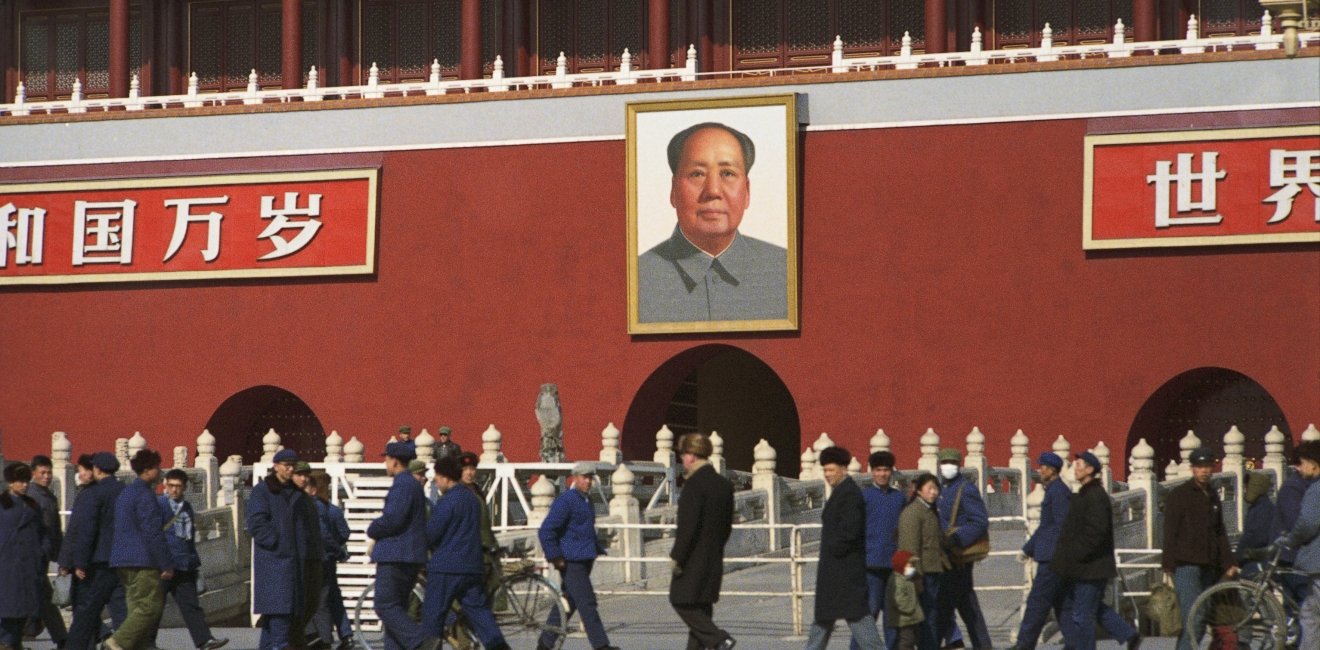

The new documents on the Chinese Foreign Policy Database were originally compiled by Wang Chaoxing (王晁星), an instructor in the Philosophy Department at Wuhan University. During the Cultural Revolution, Wang collected hundreds of Mao’s speeches and writings, which covered the Communist Party Chairman’s life up to 1968. The Second Steel Division (钢二司), a rebel Red Guard faction based at the university, subsequently obtained and printed the collection for internal circulation in May 1968. The publication was comprised of five volumes, nearly 1600 pages in length, and titled Long Live Mao Zedong Thought.[1]

The full texts for this edition of Long Live Mao Zedong Thought are available online through the Marxists Internet Archive, as well as in print from the Service Center for Chinese Publications (Los Angeles).

We combed through the complete edition to identify all conversations that Mao held with non-Chinese individuals after the founding of the PRC in 1949. We then developed descriptive metadata for each record. Synopses with authorship, subject, and geographic tags provide important context for each record, enhancing discoverability and orienting individual documents in relation to others. This way, users may search for alternate versions of Mao’s encounters with foreigners, which are already accessible on the Database, and then verify and/or question the authenticity of the records as they are documented in the 1968 printing of Long Live Mao Zedong Thought.

The post-1949 conversations with non-Chinese individuals that we found in Long Live Mao Zedong Thought date from 1956 to 1967. In those 11 years, Mao Zedong met with a variety of public figures from throughout Asia, Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe. He not only received official delegations of politicians and diplomats but also engaged with educators, journalists, and writers, like the Cuban poet Félix Pita Rodriguez. Furthermore, he received guests from countries that were often at odds with China, like the United States, Great Britain, Australia, and Japan. For example, Mao met with Bernard Montgomery, a British Field Marshal and the Viscount of Alamein, for the first time in May 1960.

The documents vary considerably in length. Many are brief excerpts of Mao’s remarks. Others feature complete or nearly complete conversations, including the back-and-forth dialogue between Mao and his foreign guests. When the American journalist Edgar Snow interviewed Mao in 1965, he recorded that their conversation was quite unusual because it lasted for four hours.

Mao’s choice of conversation topics ranged from politics to the role of intellectuals at home in China. He often called for states in the socialist bloc to unite with their anti-imperialist counterparts in Asia, Africa, and Latin America so that they could defeat American imperialism together. Documents from later periods also feature Mao urging his anti-imperialist and socialist visitors to guard their countries and respective communist parties against Soviet revisionism. According to Mao, the Soviet revisionists were “proceeding toward the restoration of capitalism” while the imperialists and reactionaries of the world were “ghosts” and “paper tigers” (or sometimes "tofu tigers").

As presented in Long Live Mao Zedong Thought, from the late 1950s and into the early 1960s, nearly every one of Mao’s conversations with foreign guests declared his stance against American imperialism and Soviet revisionism.

In terms of support for anti-imperialist and socialist movements around the world, Mao urged everyone to take action. He considered his visitors as friends and allies as long as they opposed American imperialism and Soviet revisionism. Whenever Japanese socialists tried to apologize for the Second Sino-Japanese War, he would argue that the Japanese invasion in fact helped to unify the Chinese people. Then, he would steer the conversation back to the problem of American imperialism in their country.

For Mao, there were two sides to everything (一分为二), including the Second Sino-Japanese War, and this meant that he saw two sides to the issue of American imperialism as well. Several of the documents presented in Long Live Mao Zedong Thought show that Mao knew about the US civil rights movement and that he expressed support for African Americans throughout the mid-1960s.

Other documents highlight ways that Mao thought about domestic issues in relation to geopolitics. During a meeting with East German officials in 1959, Mao cited the student protests that stoked the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 when offering reasons for China to both use and control intellectuals. From Mao’s perspective, the Hungarian protest offered a significant lesson for communists around the world, which the Hundred Flowers Campaign also confirmed in late 1956 and 1957. When the intellectuals rebelled, it almost seemed like the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would perish. Mao’s distrust of intellectuals often surfaced in conversations with foreign educators or experts, and this skepticism would become especially apparent once he began explaining the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) to foreign guests.

By examining these 58 Chinese documents, we can see that although Mao received a variety of foreign guests from many different countries and territories over 11 years, his convictions never changed. His ideology, “Mao Zedong Thought,” remained consistent throughout this time.

[1] “1968 年武汉版《毛泽东思想万岁》,” The Chinese Marxists Library (中文马克思主义文库) (Marxists Internet Archive, 2005), https://www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/1968/; Gang er si Wuhan daxue zongbu et al, eds., Mao Zedong sixiang wansui (Long Live Mao Zedong Thought) (Wuhan, internal circulation, May 1968).

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more