Vladimir Putin’s Stasi ID: A Press Sensation and Its Historical Reality

Why did Vladimir Putin have an East German Stasi ID card? The answer is rather simple, writes Douglas Selvage.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Why did Vladimir Putin have an East German Stasi ID card? The answer is rather simple, writes Douglas Selvage.

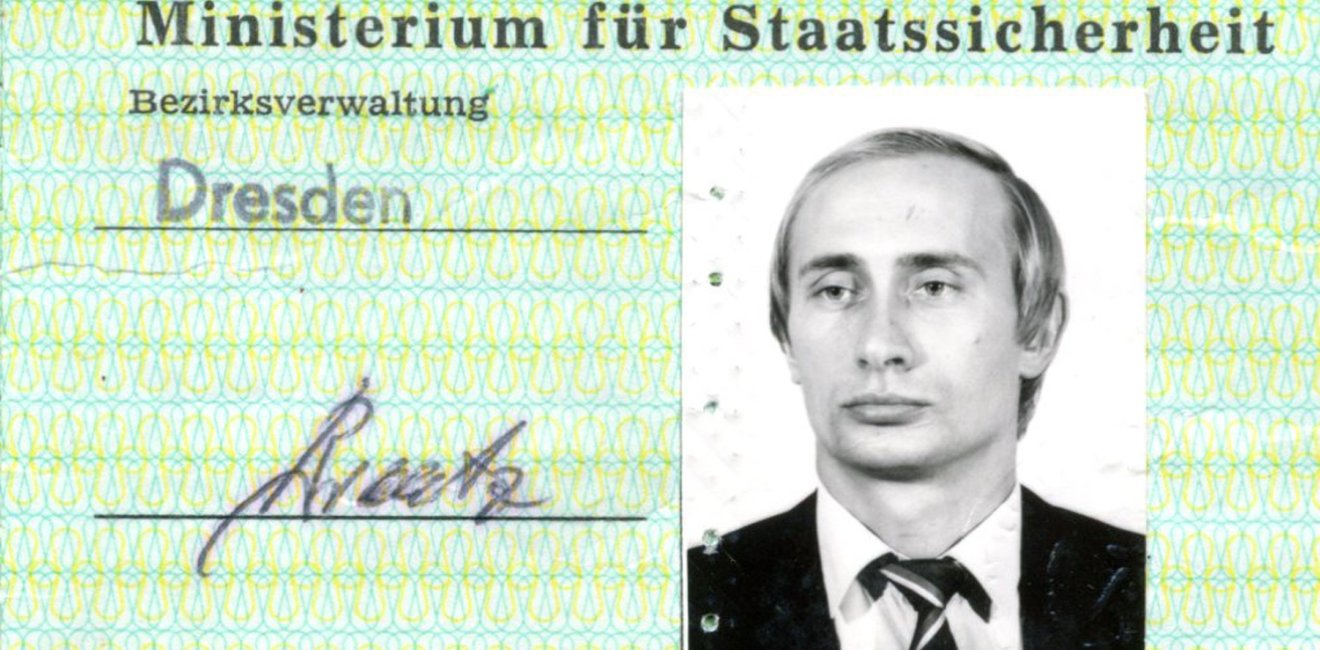

Recently, a press sensation began in Germany and spread across the globe when an identification card from the East German Ministry of State Security (MfS, or Stasi) was found in the Stasi Records Archive with the name and picture of the Russian President Vladimir Putin.

(On a personal note, I did not find the ID card, despite some early press reports to the contrary.)

It has been a well-known fact that Putin served from 1985 to 1990 as a KGB officer in Dresden; now, some journalists decided, he had worked for the Stasi as well!

It turns out, of course, that this was not the case.

As historians know and point out again and again when such “sensations” spread through the press, the situation is usually more complicated than expected. But in this case, the situation is actually much simpler.

A single, very technical, and admittedly boring-looking document brings us closer to the truth than the flashy, colorful Stasi ID with the photograph of a now famous (or infamous) person.

Specifically, I am referring to a document from the Stasi archives that the Wilson Center posted online in English translation in 2012 which bears a very bureaucratic title: “Protocol Regulating the Cooperation between the GDR’s Ministry of State Security and the Representation of Committee for State Security [KGB] of the Council of Ministers of the USSR to the Ministry of State Security of the GDR.” The original file in German is also available on the website of the Stasi archives.

Article V of this 1978 agreement between the KGB and Stasi states:

“Liaison officers from the Representation of the KGB to the MfS of the GDR, as well as other employees from the Representation of the KGB to the MfS of the GDR designated to maintain contacts with directors of units of the MfS of the GDR, will be provided with official documents from the MfS of the GDR. They will allow them to enter office buildings of the MfS of the GDR in order to fulfill the tasks outlined in Article III of this protocol.”

That is, Putin—just like other KGB officers—received a Stasi ID so that he could easily enter the Stasi headquarters in Dresden, where he could discuss “operational matters” with his Stasi colleagues.

The subjects of such potential meetings are described in Article III of the same agreement. They included:

It is possible that Putin, as some press reports have suggested, dropped by for lunch in the cafeteria with Stasi colleagues, but nothing has been found in the Stasi archives to suggest this.

Although one press report citing me suggested that Putin met with his German agents in the Stasi building, this was likely not the case. The KGB had its own “conspiratorial apartments” in Dresden, where its officers could meet with agents. Putin more than likely discussed with his East German colleagues potential targets for recruitment among the local population, foreign students, and visitors to Dresden.

This was typical of mid-level KGB agents – such as Putin – who were stationed in East Germany at the time, especially outside of East Berlin. He was also active on the Soviet side in organizing the activities of the local KGB and Stasi branch of the German-Soviet Friendship Society. This was a likely topic of conversation for him at the Dresden Stasi headquarters as well.

Summing up, it is no surprise that Putin had a Stasi ID, given the day-to-day cooperation between the KGB and Stasi. Its discovery among the last five-percent of the Stasi archives in Dresden still being processed helped provoke more of a media sensation than this story deserved.

Image: A photo ID card issued to a young Vladimir V. Putin by the Stasi. Source: BStU, MfS, BV Dresden, HA KuSch, Nr. 7216, pp. 4a-4b.

Credit

Cr

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more