Watching Beijing from Berlin

East German and other socialist bloc officials carefully watched any emerging Chinese rapprochement with West European countries and the United States.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

East German and other socialist bloc officials carefully watched any emerging Chinese rapprochement with West European countries and the United States.

China chose to “lean to one side” in the Cold War and join the socialist camp after the 1949 revolution. Numerous Soviets and East Europeans were in China in the 1950s, not just as diplomats and embassy officials but as advisors, teachers, specialists, and technicians in countless areas of Chinese society and the Chinese economy. Their reports and impressions were informed by a first-hand knowledge of daily life in China, in contrast to those of Western observers.

The early documents in the History and Public Policy Program’s newly published collection of East German (GDR) sources – all of them competently translated by Bernd Schaefer – address leadership politics, the role of the military, violence and economic disruption during the Cultural Revolution, upheaval in the universities, mass rallies and show trials, Sino-Soviet border conflict, Chinese foreign policy in Africa, the cult of Chairman Mao, the Vietnam War, and China’s emerging relationship with the United States.

The East German and socialist bloc discussions were informed by a strong sense of China’s betrayal of the bloc, and China’s tragic deterioration and descent into a Maoist dictatorship. “The CCP leadership exploited experiences and support of the socialist countries for its socialist build-up,” claimed East German official Heribert Kunz in a 29 December 1969 note, paraphrasing a presentation from the Hungarian ambassador. China was now attempting to “isolate and split” the “fraternal socialist countries” from the Soviet Union, shaped by Mao’s ambitions and “great power chauvinism.”

Like many other socialist bloc officials, Kunz warned of “differentiation,” a Chinese effort to challenge Soviet leadership of the bloc by reminding East Europeans of their relationships to China independent of the Soviet Union and of their common struggles with the Soviet system and Soviet “imperialism.”[1] A Czechoslovak report from October 1964 describes the hopeful but unsuccessful efforts of Chinese Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai to court the East Europeans after the ouster that month of Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev, an event sure to have a “positive influence on China’s relations with the Soviet Union and the fraternal countries.”[2]

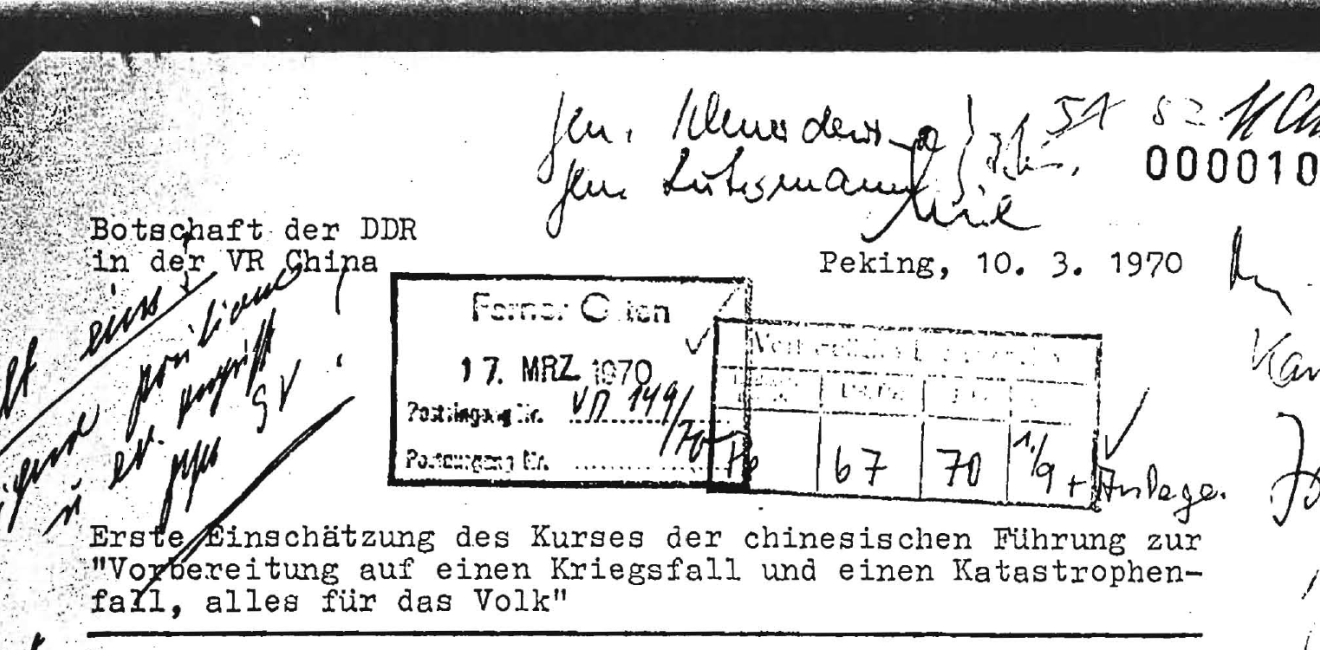

Instead the East European, and especially the East German, search for security and legitimacy remained tied to the alliance with the Soviet Union, soon to be realized in the end of the West German “Hallstein Doctrine” and the signing of the Basic Treaty between Both German States of 21 December 1972.[3] The Chinese effort to weaken the socialist bloc led by the Soviet Union would ultimately serve the interests of the United States, complained East German official Dr. Bettin in a 10 March 1970 embassy report. The United States was already taking advantage, he suggested, attempting “to exploit the Maoist policy for implementation of their own global strategy.”

As the materials here suggest, East German and other socialist bloc officials carefully watched any emerging Chinese rapprochement with West European countries and the United States, fearful and apparently well aware of the likely long-term consequences for the socialist world of the emerging “tacit alliance,” as Danhui Li and Yafeng Xia put it, between the United States and China.[4] The Sino-Soviet split, writes Julia Lovell, “initiated the slow death of the Soviet bloc.”[5]

[1] See James G. Hershberg, David Wolff, Péter Vámos and Sergei Radchenko, “The Interkit Story: A Window into the Final Decades of the Sino-Soviet Relationship,” Cold War International History Project Working Paper Series 63, or 31 January 1969, “Protokoll,” SAPMO DY 30/11929, 1-64.

[2] "Telegram z Pekingu," Křístek, October 30, 1964, NA KSČ--AN--II, krabice 84, folder "Telegramy, sífry, depresè, zpravy."

[3] Werner Kilian, Die Hallstein-Doktrin: Der diplomatische Krieg zwischen der BRD und der DDR, 1955-1973 (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2001).

[4] Danhui Li and Yafeng Xia, Mao and the Sino-Soviet Split, 1959-1973: A New History (Lexington, Massachusetts: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018). See also Evelyn Goh, Constructing the U.S. Rapprochement with China, 1961-1974: From "Red Menace" to "Tacit Ally" (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

For similar East German fears about the consequences of the “anti-Soviet conceptions” of the “Mao-Group” in China, see 20 July 1971, Schneidewind to Lothar Strauss; 19 May 1971, Liebermann to Gustav Hertzfeldt, MFA PAAA C 1083/73, 23-27; 5 May 1970, “Informationsbericht des ADN-Korrespondenten in Hanoi,” Feldbauer, MFA PAAA C 1083/73, 64-68; 8 February 1971, “Vermerk über ein Klubgespräch der Botschafter und Geschäftsträger, Lothar Strauss, MFA PAAA C 504/75, 10. On the various “cards” played by the United States and China, see Margaret MacMillan, “Nixon, Kissinger, and the Opening to China,” in Fredrik Logevall and Andrew Preston, eds., Nixon in the World: American Foreign Relations, 1969-1977 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 107-124; Yafeng Xia, “China’s Elite Politics and Sino-American Rapprochement, January 1969-February 1972,” Journal of Cold War Studies, vol. 8, no. 4 (Fall 2006), 3-28.

[5] Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2019), 147.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more