Working in archives sometimes yields unexpected discoveries.

As I was researching the files of the Soviet embassy in Kabul for my upcoming book on the Soviet-Afghan War at the Russian State Archive of Contemporary History (often known by its Russian acronym, RGANI), I came across documents on a different and seemingly unrelated topic: the possibility to organize a chess match between the Soviet grandmaster Anatoly Karpov and the American grandmaster Bobby Fischer in 1976-1977.

Although aspects of that story are fairly well known, thanks to a book published by Dmitry Plisetsky and Sergey Voronkov, several questions remain as to why that title match was ultimately never organized.[1]

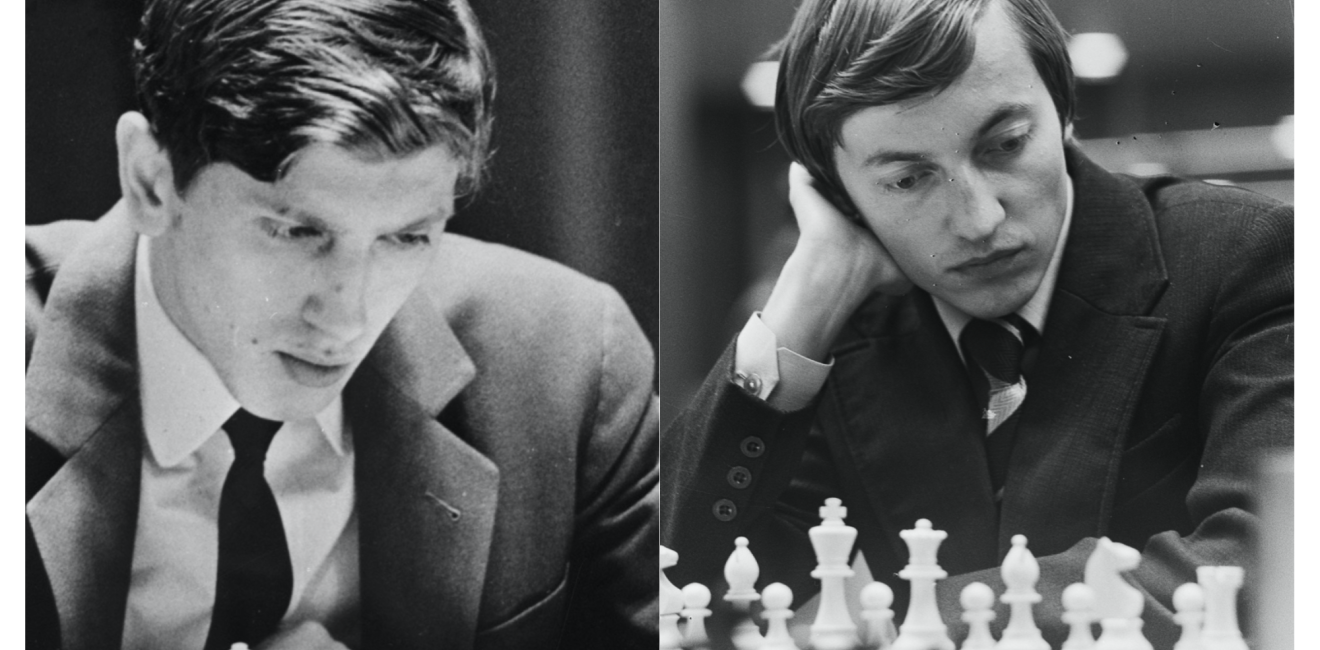

First, some background: In 1975, Karpov returned the title of world chess champion to the Soviet Union after Fischer had captured it from Soviet grandmaster Boris Spassky in the 1972 “match of the century.”

Fischer’s victories over Soviet grandmasters were a monumental blow for the USSR, reverberating through the highest levels of the Community Party (CPSU). A lone and self-made American chess champion, who had perfected his play by studying Soviet and other foreign chess journals, had crushed all of the top Soviet players. While doing so, he had (likely correctly) accused the Soviet players of colluding during chess tournaments to ensure that a Soviet always came out on top.[2] Fischer’s latest accusation had even forced the International Chess Federation (FIDE) to change tournament rules.

Fischer crushed Spassky in 1972, despite Spassky benefitting from the support of the Soviet chess community, by far the largest and strongest in the world.[3] Unlike today when each chess player worries about his or her own career, the CPSU would tell Soviet grandmasters that the title was a matter of national interest – not personal interest – and that they had to support, in whatever way needed, the Soviet player vying for it. This meant sharing, without compensation, their preparation for chess games and analysis of potential foreign opponents (such as Fischer) and helping to train for title matches.

By bringing the title back home in 1975, Karpov became a hero in the Soviet Union. He was young at the time – only 24 years old – and heralded a new generation of Soviet players not beaten down by Fischer. Many observers considered Karpov to be one of the most talented players in history.

Yet, there was a problem with Karpov’s title in 1975. Karpov did not win the title by defeating Fischer, but rather because the American player forfeit the match.

After protracted negotiations, the Soviet and American sides were not able to agree on the conditions for the title match. Thus, Fischer, the defending champion, had tried to impose a new set of rules prior to the match. The new rules proved unacceptable to the Soviets and to most of FIDE, which was itself deeply split over the issue. Ultimately, while many observers doubted that Karpov could capture the title in a match, the Soviet authorities were all too happy to oppose Fischer’s proposed changes. After Fished refused to play the title match based on the old rules, FIDE stripped him of his title in favor of Karpov.

Without debating the particulars of Fischer’s suggested changes, it is clear that the absence of a title match had left chess enthusiasts around the world deeply frustrated. The situation resulted in widespread questions about Karpov’s legitimacy as the world chess champion. It also upset Karpov himself, who wished to play Fischer and prove himself.

The documents I located at RGANI were produced in this context and show how Karpov and others reached out to the CPSU to try to organize a title match with Fischer in 1977.

In October 1976, Karpov wrote a letter to Sergei Pavlov, the Chairman of the Committee for Physical Culture and Sport to the Council of Minister of the USSR. An influential apparatchik, Pavlov had ended up in charge of sports in the USSR for 15 years after having headed the powerful Komsomol for nine years. A close ally of Alexander Shelepin (a member of the hardline faction in Nikita Khrushchev’s era), Pavlov was sent to handle Soviet sports after Shelepin lost the battle for power to Leonid Brezhnev in the late 1960s.

In his letter, Karpov made several interesting points. He first explained how he had met Fischer in Tokyo in July 1976 on, he insisted, Fischer’s initiative. Fischer had then suggested that they play a public chess match against each other. To appease CPSU officials, Karpov immediately noted that he “understood perfectly well not only the sports, but also the other aspects that such a game would entail,” and, therefore, while not refusing in principle, he did not give Fischer any answer.[4] Yet, as he moved to explain his thinking about Fischer’s offer, it is clear that Karpov was himself very much in favor of such a game.

Karpov reminded Pavlov that he had already committed in front of Soviet and foreign journalists to play a game with Fischer when he was awarded the world chess champion title in 1975. Besides, the game would be “unofficial,” Karpov argued, because Fischer would not have gone through the challenger selection process.[5] Though a loss might affect his legacy, it would not cost Karpov – or the Soviets – the official title.

Beyond this, Karpov contended that a match against Fischer was inevitable. If Fischer was back on the world chess stage as it then seemed (Fischer had played virtually no competitive chess since winning the title in 1972), he would quickly dispose of the older generation of grandmasters that he had already crushed before; only Karpov could stop him.

Karpov then went on to detail his impressive record since becoming world champion. “There is no reason for me to avoid meeting the American behind the chessboard,” he declared. “Our motherland needs a chess king, and not, as the foreign press writes, - ‘a prince, with the prerogatives of a king [nadelennyi korolevskimi polnomochiyami]’”.[6]

The comment was telling of Karpov’s frustration at the challenges to his legitimacy, despite having beaten many top chess grandmasters and building a streak of tournament victories that would continue into 1977. Karpov hence appealed to the Soviet authorities by suggesting that they too should be interested in a champion whose legitimacy was beyond doubt. The bottom line was, Karpov added, that he had to play Fischer to prove himself against the best grandmaster of the past decade. It was better to do it sooner than later because Fischer was not at his peak after coming out of semi-retirement. Karpov, though, did not find any support in the CPSU.

Yet, the story was not over. Prominent FIDE officials and even a foreign leader took the lead in trying to organize a new “match of the century”. Florencio Campomanes, a Filipino national who would become FIDE’s president in 1982, travelled to Moscow to personally appeal to Brezhnev on this issue in December 1976. As reported by Pavlov to the Central Committee of the CPSU, Campomanes was one of these people “who showed excessive persistence in their attempts to organize the [Fischer-Karpov] game.” To this end, “he had organized in 1976 two unofficial meetings between R. Fischer and A. Karpov” in the Philippines.[7]

Putting pressure on the Kremlin, Campomanes had even passed a letter from the President of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos, to Brezhnev.[8] Marcos assured Brezhnev that he would be willing to support any type of arrangement to have the game in Manilla. Campomanes even told the Soviets that the Philippines were ready to guarantee a $3,000,000 prize fund for the game. This was an enormous amount for a chess match, and much more than the $250,000 prize fund of the Spassky-Fischer game in 1972. The massive prize fund was certainly another factor that (understandably) raised Karpov’s and Fischer’s interest in the match. In passing, Campomanes’ mission and Marcos’ letter both suggested that Karpov had been more involved than he had reported in the negotiations regarding a potential game with Fischer.

Yet, the Soviet answer did not change. While reporting on Campomanes’ visit, Pavlov clearly explained that, “based on the principled position adopted by CC CPSU,” Campomanes was informed that it was impossible to hold such a chess game for various reasons.[9] Pavlov resorted to the old argument that Fischer’s conditions were unacceptable for Karpov, a weak retort given that Karpov himself had pushed for the game just weeks prior and met with Fischer. The decision to not move forward with the game was confirmed by the Department of Propaganda of the CC CPSU. It had already argued against a Fischer-Karpov match in summer 1976 by deeming it “impractical.”[10] The bottom line seemed to have been that, at this point, the Soviet leaders felt that there was no reason to risk the hard-won world chess champion title. A victory by Fischer, which many international grandmasters anticipated, even in an unofficial game would have raised the question of Karpov’s legitimacy. It may have resulted in pressures from FIDE and the international chess community to have an official title match.

The idea of a Fischer-Karpov game resurfaced in late 1977 after another meeting between Karpov and Fischer. The Soviet grandmaster reached out again to the Soviet leadership to suggest a match, if he managed to successfully defend his title against the official FIDE challenger in 1978. According to one account, Pavlov this time agreed to the game, receiving the support of Mikhail Suslov, the chief Soviet ideologist.[11] Both seemed to believe in Karpov’s chances of winning by that point, probably due to Karpov’s string of tournament victories.

Yet, the much-awaited match never happened. To this date, it is unclear why Fischer, who had become increasingly erratic in his behavior, and the Soviets proved unable to organize it.

This short essay illustrates how chess was a prime field of the cultural Cold War, much more than a game for the Soviets and Americans. In Moscow, it was seen as an example of Soviet intellectual dominance and a key area where it was unthinkable to yield to the Americans. It was essential to “consolidate the authority of the Soviet chess school,” Karpov argued to Pavlov in late 1977.[12] It also showed how top Soviet officials, including ideologists, were involved in managing Soviet chess prestige. Few, if any sports, stood at the same level as chess.

In Washington, the appearance of Fischer came as a unique opportunity to beat the Soviets at their own game. Despite the difficulty of managing the capricious Fischer, US policymakers had rapidly co-opted his chess successes into their foreign policy. Henry Kissinger famously phoned Fischer during his match with Spassky to urge him not to withdraw.[13] Yet, unlike Soviet grandmasters, Fischer, who had regularly criticized the Soviet system, remained his own man and refused to become a cultural ambassador of the West.

Chess was interestingly also a rare opportunity for Third World countries to play a role in the cultural Cold War. Hosting chess tournaments was a relatively affordable and prestigious way for them to extend their influence through sports. Argentina had hosted the candidates final between Fischer and the Soviet grandmaster Tigran Petrosian in 1971.

Manilla, as we saw, would come to be a central actor in chess as Campomanes ascended in the FIDE bureaucracy and Marcos offered his patronage. After failing to arrange the Fischer-Karpov match, the Philippines hosted the high-profile world chess title match between Karpov and Victor Korchnoi in Baguio in 1978. In an event marred by multiple controversies, Karpov narrowly defeated Korchnoi, a former Soviet grandmaster whom he had already beaten to become the title challenger in 1974 (the CPSU had then apparently blocked other Soviet grandmasters from assisting Korchnoi in his preparation) and who had since defected to the West. After that, as Garry Kasparov appeared on the chess horizon, the battle for the chess world championship became again a solely Soviet affair.

[1] Dmitry Plisetsky and Sergey Voronkov, Russkie protiv Fishera (Moscow: Ripol Klassic, 2004). While the book may be difficult to find in English (Dmitry Plisetsky and Sergey Voronkov, Russians versus Fischer (London: Everyman Chess, 2005)), an electronic version in Russian can be easily found online.

[2] Charles C. Moul and John V. C. Nye, “Did the Soviets collude? A statistical analysis of championship chess 1940–1978”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 70, no. 1-2 (2009): 10-21.

[3] On Soviet chess: Seth Bernstein, “Valedictorians of the Soviet School Professionalization and the Impact of War in Soviet Chess”, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 13, no. 2 (2012): 395-418.

[4] “Predsedatelyu komiteta po fizicheskoi kul’ture”, 1 October 1976, RGANI, fond (f.) 5, opis’ (o.) 69, delo (d.) 94, list (l.) 21.

[5] Ibid., l. 22.

[6] Ibid.

[7] 11 January 1977, RGANI, f. 5, o. 69, d. 94, ll. 26-27.

[8] 22 October 1976, RGANI, f. 5, o. 69, d. 94, ll. 28-29.

[9] 11 January 1977, RGANI, f. 5, o. 69, d. 94, ll. 26-27.

[10] “O besede v sportkomitete SSSR”, 28 January 1977, RGANI, f. 5, o. 69, d. 94, ll. 30-37.

[11] Plisetsky and Voronkov, Russkie protiv Fishera, 487-88.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Kissinger Phone Call to Fischer Disclosed”, The New York Times, 18 July 1972. https://www.nytimes.com/1972/07/18/archives/kissinger-phone-call-to-fischer-disclosed.html